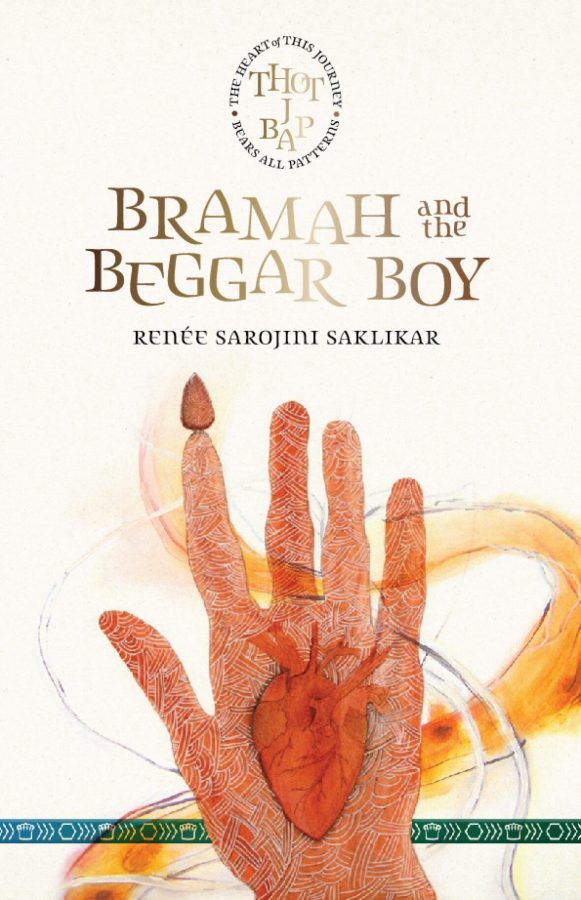

Renée Sarojini Saklikar’s Bramah and the Beggar Boy was published by Nightwood Editions in 2021

Faced with today’s urgent issues, the necessary alterations in behaviour needed to ensure a continued place for ourselves and other species on this planet, some writers might feel like giving up, not on activism but on writing as activism’s vehicle. In her “epic fantasy in verse,” Bramah and the Beggar Boy, Renée Sarojini Saklikar takes it all on with courage and gusto, with everything she has as a writer. The first book to emerge out of her life-long poem project, THOT J BAP (The Heart of This Journey Bears All Patterns), Bramah is a remarkable document of imagination, literary influences, and projected history.

Over time the word verse has shifted from the Latin versus, “a turn of the plow, a furrow, a line of writing,” to any metrical composition from lament to limerick. It serves as a commodious contraction (‘verse for universe) and as a suffix to indicate a particular world (e.g. metaverse). In Bramah, Saklikar shifts what we traditionally expect from epic verse, intermixing elements of prose and speculative fantasy to dismantle orthodoxies of high and low and engage her readers with several different literary styles. The verse in this epic fantasy is not about the lone hero’s journey, but about all of us, now, and where we might be headed. In the book’s dystopian future of eco-catastrophes, viral bio-contagion, and cruel governance, Saklikar amplifies rather than invents themes that reverberate in our present disasters.

It’s a complex narrative, not easily summarized, that moves from a dark time to come called the Far Future, back to 2020 when our pandemic began, and forward to 2050. There is no bard but there is the young demi-goddess Bramah, a locksmith who can time travel through seasonal portals. Unlike Joseph Bramah, who invented the tamper-proof lock in 1784, she is not an old white guy but a “brown, brave, and beautiful” girl. With a shift of a letter her name hints at Brahma, the Creator in the triumvirate of Creator, Maintainer, and Destroyer of Hindu mythology. Bramah, not exactly the Creator, has the key to the mysterious old box with its seemingly infinite store of scraps, clues to what has been and is always being created. This female Bramah has magic, but not inflated, powers. The Beggar Boy she takes under her wing doesn’t speak and seems to have no name. The other Beggar Boys, sometimes huddled outside Perimeter, powerful Consortium’s wall, chant their rhymes of need and hunger and keep the stories of the female heroes alive.

Saklikar both embraces the well-worn epic form and resists it, with a proclamation of its creative possibilities and the elevation of these (mainly) women would-be saviours/warriors: the female scientist Dr. A.E. Anderson; the four wise Aunties who save seeds and pass on plant knowledge; the grandmothers who take in, raise, and sometimes adopt the orphans (including Abigail, the main character in the last part); the banished but clever Sword Girls; and the titular character, Bramah (“Her hairs glossy black, her skin honey-brown”).

The notes that bracket the book tell us almost everything we need to know about Saklikar’s inspirations: Homer, the Mahabharata, bpNichol, T.S. Eliot, Shakespeare, Chaucer, The Arabian Nights, Dante, Keats, folk tales, speculative fiction, the Muslim and Hindu myths of her ancestors. Although interspersed with prose (spy reports, official documents), the narrative depends a great deal on metre, rhyme, line breaks, and repetition, all those techniques of verse that enabled a long story to be heard, remembered, and retold over centuries. These same techniques work in Saklikar’s epic fantasy as memory devices within the story, as carriers of hope in the dystopian future she draws for us, when literature and science have no museums or institutes to keep them safe, only the call from one voice to another. In an intriguing reversal, Saklikar projects an oral culture that might save fragments of past knowledge; it’s the disenfranchised who carry forward the seeds of renewal through all the forms of verse that survive despite the deliberate amnesia of the authoritarian state.

Help us journey, save us from the toothed margins,

No balms for bitten.

Glabrous on top, Grand-Mère said of the story-tree,

downy below.

Male, duo-male to female,

big bracts, the base, one long as the other.

Creamy white? We asked, together sang,

ovate pendulous.

— From “AUNTY MARIA TOLD US” in Bramah and the Beggar Boy: 45.

If the narrative of Bramah sometimes sits uneasily atop and around the music, rather than flowing as one strong stream, it might be that poetic language resists the logical arc of set-up, conflict, and resolution. Although we often want a story that compels us to keep reading, a poem’s imperative is to slow us down to its moment. So, while we could read this book from front page to last, we might just as easily be captivated by a single poem found at random wherever the pages open, like a point on a map, and begin the story there.

Seasons of mists, those Beggar Boys sang soft,

magical island of primrose and mist

bribe the Ferryman to give you the list.

Thatched eves, winnowing wind, high in the loft.

Shift-Tilt: our seasons ran cold, marble halls

We called out, chained, from departing buses—

Draco in three thousand, Vega in twelve

Those Beggar Boys replied, their small hands raised—

Draco in three thousand, Vega in twelve

Marble halls, where seasons ran cold, tilt-shift

This present, that is our future

We’ll come back—in twenty-five-nine-two-oh

We’ll come back—in twenty-five-nine-two-oh

— From “RETURN TO THE WINTER PORTAL” in Bramah and the Beggar Boy: 141.

Bramah and the Beggar Boy made me think deeply about writing and inspiration. With its many layered references, it takes us through the rich literary traditions of past and present, high and low, written and oral, cut up and pasted back together to make something new. Saklikar’s cry of “Jumped the fence, you should too—” suggests we look for wisdom and hope beyond Perimeter, beyond the enclaves of power, literary or otherwise. Repeated refrains from Stephane Mallarmé’s poem “Un Coup de Dés Jamais N’abolira Le Hasard” (A throw of the dice can never abolish chance), acknowledged as the pivot to literary modernism, suggest that nothing is fixed. “Jamais, Jamais….”

I was left anticipating what will follow this remarkable book and how Saklikar’s energy and ambition will continue to confound any attempts to attach easy labels to her poetic project. As for the future she imagines for us, there is always the chance of an unexpected outcome.