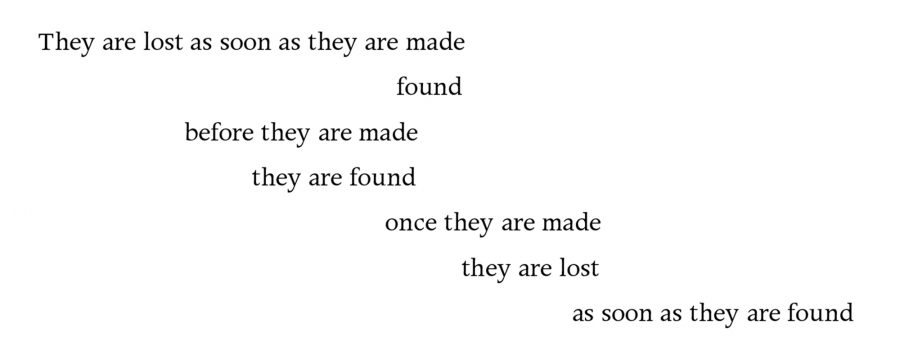

They are lost as soon as they are made is an artist book by Karen Zalamea. The following text is excerpted from the book’s opening essay “being in weather” by Katie Belcher.

In The Miracle of Analogy, art historian Kaja Silverman describes photography as a means by which the world reveals itself to us by “demonstrating that it exists, and that it will forever exceed us.” [1] Silverman unearths in philosopher Walter Benjamin’s texts a position that photography is “a disclosive rather than an evidentiary truth,” finding that he “attributes it to the world, instead of to technology, treats it as an analogy, instead of an index or a copy, and associates it with development, instead of fixity.” [2] The photographic analogy therefore “develops, rather, with us, and in response to us.” [3]

In composing her photographs, Zalamea chose information that may have registered photographically—there were certainly preferred, or at least anticipated, results. While some subjects are evident, other images are purely textural. Some of the ice lenses resulted in fractures, drips, and disruptions in the negatives themselves. But also, Zalamea explains, “some of the photos include watermarks or chemical drips on the developed negatives, and arguably these were not present during the exposure. I’ve decided to keep them in as a continuation of the liquid process.” [4] Zalamea’s 2019 exhibition at Vancouver’s Access Gallery, Subarctic Phase, [5] featured an imposing grid of images—each a larger format than you see in this publication. The viewer was confronted by a collection of mostly unrecognizable forms in varying tones and hues—the reiteration of the grid disrupting any search for a dominant horizon. As I imagine you, the reader, holding this publication in your hand, I recall my first encounter with these works, in the artist’s studio, where I held four-by-five-inch prints of these images as singular objects. In this context, Zalamea asks us to attend to each image carefully, more intimately than when experienced in the vast, atmospheric grid of the exhibition. These two wildly different presentations of the same images mirror our consumption of landscape—the vast and the minute; fore and background; the body and the eye.

Anthropologist Tim Ingold proposes that scholars have, for generations, hinged their art historical analysis of landscape on an etymological error. [6] The suffix “-scape” originates from the Old English sceppan (to shape) and “-scope” from the classical Greek skopos (a bowman’s target). So, landscape came to be associated with descriptive scenery and aligned with pictorial renderings by painters—and later photographers.

Forming water into a mechanism for taking scope, Zalamea steps into the role of landshaper, giving renewed attention to the materiality of landscape and the labour of being perceived. The ice lenses redirect a photographic attention from striated to smooth space, aiming to witness the experience rather than to record a view. Zalamea’s project as a whole—both materially and conceptually—attends to both the haptic and the optic nature of being in landscape.

The series’ title—They are lost as soon as they are made—is pulled from a description of footprints pressed into the snow in the novel Independent People by Halldór Laxness. [7] The image speaks to weather, to mark making, to the embodied experience of moving from one space to another, and to the landscape’s temporality. Zalamea’s images are more analogous to impressions than to inscriptions. Silverman challenges the notion that a camera is necessarily either an indexical tool pointing directly to an absent referent—just as footprints in the snow attest to the existence of the person who made them—or an aggressive tool used by a human to assert power. [8]

[1] Kaja Silverman, The Miracle of Analogy, or, The History of Photography (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014), 11.

[2] Silverman, The Miracle of Analogy, 8.

[3] Silverman, The Miracle of Analogy, 12.

[4] Zalamea, in conversation with the author, March 2019.

[5] Subarctic Phase ran April 27 to June 14, 2019.

[6] Tim Ingold, “Landscape or weather-world?,” in Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description (London: Routledge, 2011), 126–27.

[7] Halldór Laxness, Independent People (New York: Vintage Books, 1997). Originally published in Icelandic as Sjálfstætt fólk in 1934–35.

[8] Silverman, The Miracle of Analogy, 3.