This piece originally appeared in Issue 3.27 (Fall 2015).

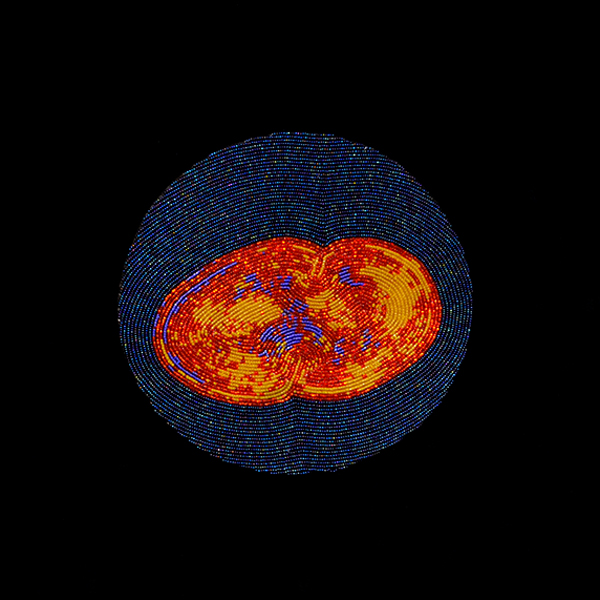

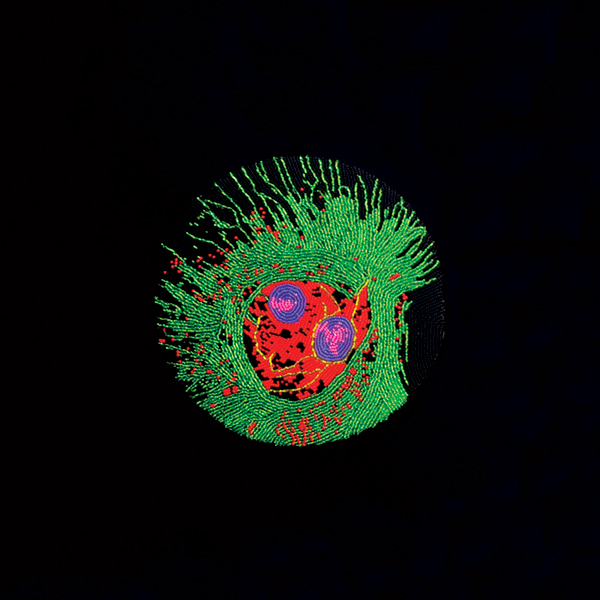

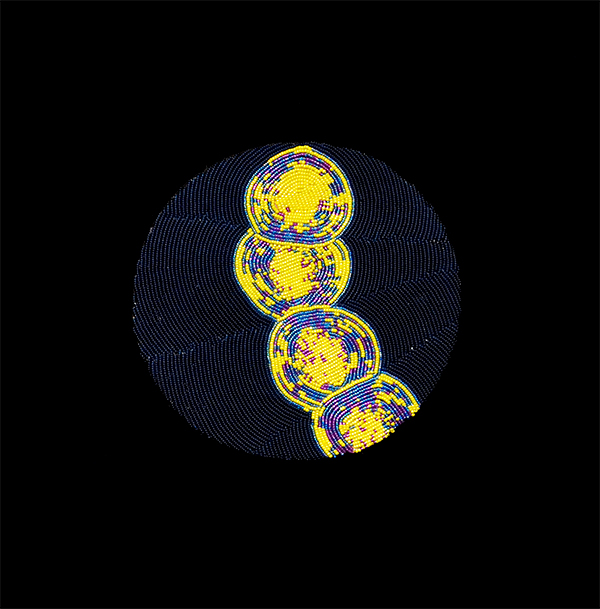

My Trading, Reserving, and Surviving series, a three-part project I began in 2008, is about the diseases affecting Indigenous populations in North America. The Reserving series, works from which are featured here, addresses the mid-1880s, when First Nations were forced to abandon their traditional lifestyles and move onto reservations, up to the 1980s, the beginning of the contemporary era of new diseases. I have rendered magnified images of the relevant diseases—Pneumonia, Smallbox, Polio, Tuberculosis, and Spanish Flu—in glass beads. Glass beads were likewise introduced to Native populations by European traders. They quickly replaced the comparatively difficult-to-work-with traditional medium of porcupine quills.

I think the process of “budding,” in which a disease replicates and exhausts the energy of its host cell, as analagous to the process of colonization. “Beading” is different. It is an activity of survival. It is a means of remembering tradition and of feeling well.

Don’t Drink, Don’t Breathe, my most recent exhibition, is about the serious housing and infrastructure problems afflicting First Nations communities in northern Canada. These communities are allotted a certain amount of money for housing, but the government does not factor in the steep cost of shipping building materials to remote areas. As a result houses have to be built on the cheap. I have seen shacks built by the Attawapiskat First Nation in Ontario with roofs mad of blue plastic tarp. They can barely stand up to the weather, let alone the wear and tear of multigenerational families. A housing councillor put it to me like this: “How often is your front door opened everyday? The front door of a typical home on the reserve is opened about 100 times a day.” Respiratory illness due to mold is rampant on reserves, as are waterborne illnesses.

The work itself consists of a formal banquet tablecloth made of blue tarp and beaded with a black mildew pattern designed to look like a bouquet of flowers. The beads are matte black, much like real black mold. Placed on top of the table are 139 water glasses containing a beaded bacterium encased in resin, representing each of the reserves across Canada that has a standing boil water advisory. (It’s an entrenched problem; one reserve outside of Winnipeg has been under a boil water advisory for over twenty years.) From afar the tablecloth and water glasses look beautiful, inviting. As viewers come closer, however, it becomes clear that they are not looking at something beautiful but rather at something ugly.