Hannah Darabi’s work “Enghelab Street, a Revolution Through Books, Iran 1979-1983” formed part of the group exhibition From Slander’s Brand: Hannah Darabi, Rachel Khedoori, Ron Terada, on view at the Polygon Gallery from November 10, 2023–February 4, 2024

Hannah Darabi wants us to think about the role of books — books of photography, books of political theory — and their role in the 1979 revolution in Iran. The title of her exhibition at the Polygon Gallery in North Vancouver — Enghelab Street, a Revolution Through Books: Iran 1979-1983 — tells us this (but more than once: Enghelab means “revolution” in Farsi and refers to a street lined with bookstores near the University of Tehran). But to do so, we also have to think about the place of books in the art museum. Darabi’s Enghelab Street is an important show precisely because of the irreconcilability of these two demands.

The role of books in the revolution is demonstrated with a variety of means. There are four displays of images in a grid, corresponding to what Darabi calls “Reconstructions” I thru IV: from the origins of the revolution, to the event itself, to the “clean-up” of non-Islamic forces, and the Iran-Iraq war. In these “Reconstructions,” images from photo books published in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s are interspersed with Darabi’s own photographs (born in Tehran in 1981, the artist attended the University of Tehran during the Khatami reform period of the early 2000s). The juxtapositions are astonishing and overwhelming: a happy-go-lucky dude, arms crossed, wearing a Kiss belt-buckle next to a mysterious figure wearing radiation protection gear in a desolate lot. When they are not too easy to read, too on the nose (images of Coke and Pepsi; a TWA jetliner denoting American imperialism), they are enigmatic as much for the content as for their provenance. Colour tones, scales of shots, and genres all vary tremendously — from landscapes to crowd shots to product placements and portraits. And an occasional vernacular conceptualism: two versions of the well-known photograph of Ayatollah Khomeini at his villa in the French town of Neauphle-le-Château, or a contemporary Tehran scene with a photo-banner of sandbags next to a stack of actual sandbags.

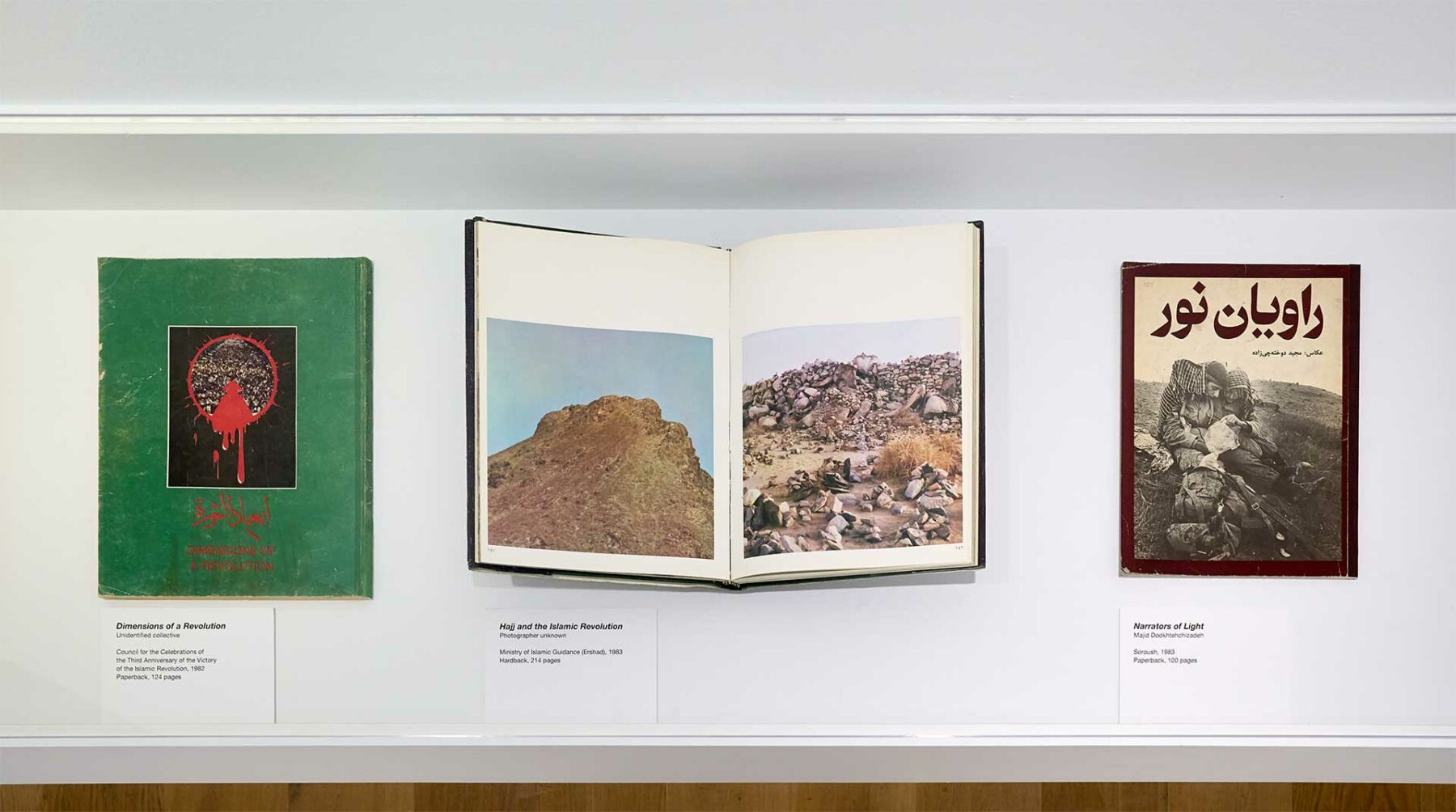

Accompanying the grids of images are books in vitrines, some displayed on table tops and others as a frieze. On horizontal tabletops, we see books opened up to display not just images but their design. Discussing her show with UBC historian Kelly McCormick in December 2023, Darabi connected the design of the exhibition with the visual culture of the photobooks. Print culture meets museology. Certainly exhibition design has, over the past decade, moved beyond the austere white-cube minimalism of the 1990s: by intention, now it is often difficult to distinguish between what is an artwork and what is contextual motif.

Three photobooks make this connection evident. In effect, they are all about the role of collage in communicating a revolution. The Epic of the Revolution of 1979, by Began Boughoussian and Morteza Khanali, is a curious mash-up of an artist’s book, zine, and political tract. Three cover pages open up to frame a brief portfolio. The three pages contain collages of contemporaneous newspaper coverage of the revolution: news as it happens (but in a Situationist or punk style), photographs, and texts laid overtop as if to convey how the information cannot be contained on the page. The folios within continue in this style, with a rare Newsweek cover (“Iran in Chaos”) that offers a sobersided contrast.

When the Walls Speak Out, associated with the leftist Islamic group Mujahedin-e Khalq, is a series of photographs of graffiti during the last months of the Shah’s regime. One tag reads: “Marx, if you could be alive today to see that religion is not the opiate of the people.” The majority of slogans were not so much pro-Islam as against the monarchist dictatorship. Like The Epic of the Revolution, this photobook is concerned with the medium of dissent: graffiti is a popular form. The irony, we are told in interviews, is that the vast majority of workers at that time were illiterate.

The Revolution in Images, by Parviz Zoumani, Hashem Faroutan, and Seifollah Samadian, perhaps aimed to fill that gap. Inspired by the visual language of revolutionary posters, the book is a bracing hodge-podge of crowd shots, overlaid slogans and images, and iconography. A hand grips a whip; a fist emerges out of a pipeline; the map of Iran holds a placard.

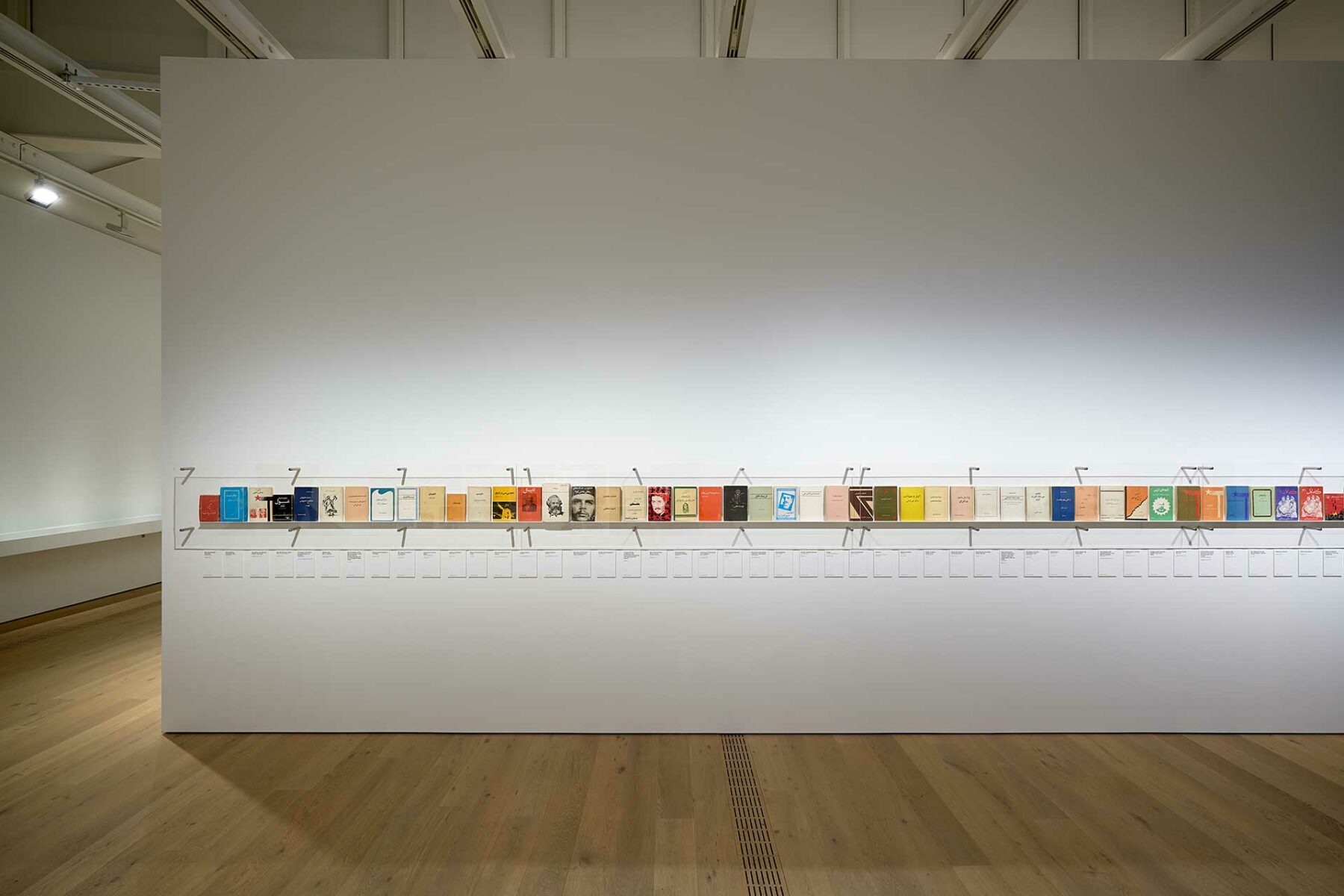

Such visual imagery stands in some contrast with another component of the Enghelab Street exhibition: the frieze of eighty or so “white covers” or political paperbacks, including translations from Mao Zedong, Võ Nguyên Giáp, Che Guevara, Karl Marx, and Friedrich Engels, as well as one of the key Iranian theoreticians of Marxist Islam, Ali Shariati. This archive — they are all from Darabi’s collection — is evidently important, even if here we have to be satisfied with admiring their range of cover designs. The ontologies of the books are flattened like an Instagram screen grab: we cannot open these books, we cannot read them.

Some of us, who can read Farsi, can read some of the open pages, or may possess copies of some of the individual volumes in Darabi’s collection-cum–exhibition. But as exhibited object, the book is surely in danger of becoming a fetish. This is due to the triangulation at work here, where the exhibition’s thesis with respect to books and their role in revolution is accomplished on the one hand by a bouleversement of the museum space as neutral frame (so images are different sizes, a flat ontology that neither distinguishes between those from the photobooks or made by Harabi, in turn faithful to the quasi-anonymous, unattributed images in the source texts) and by a locking away of the books themselves, whether in vitrines, display cases, or a video that shows pages one by one, narrated, presumably, by Darabi herself.

The critics Farzaneh Hemmasi and Hamid Naficy have warned of the dangers, in diasporic Iranian culture, of the fetishization of resistance to the theocracy — in the pop music of “Tehrangeles” and television respectively.1 Darabi’s thesis with respect to photobooks and “white covers” does not fall prey to such oversimplification. The print culture located in a specific historical moment, however, and the form by which she makes that argument — in the space of the museum — is challenged by the very objects that she collects. Enghelab Street works through the logic of not simply the agency of the book (photobooks and books of political theory as causing, or contributing to, the Iranian revolution), but the body of the book itself. In English, a book is described as having a spine, an appendix; the page has a header and a footer. In Darabi’s exhibition, the book oscillates between being an object and an image — something we can just look at. Like the martyrs of the revolution or the “Imposed War,” the book is sacrificed. It becomes a lost object.

- See Farzaneh Hemmasi, Tehrangeles Dreaming: Intimacy and Imagination in Southern California’s Iranian Pop Music (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020), 32-33; and Hamid Naficy, “Fetishization, Nostalgic Longing, and the Exilic National Imaginary,” The Making of Exile Cultures: Iranian Television in Los Angeles (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), 125-165. ↩︎