This interview was conducted in the fall of 2020 in celebration of Issue 3.42: Translingual. Damla Tamer’s Divination Objects was included and featured on the cover of the issue.

Emily Dundas Oke: Damla, could you introduce Divination Objects, and tell us a little about how this series was created?

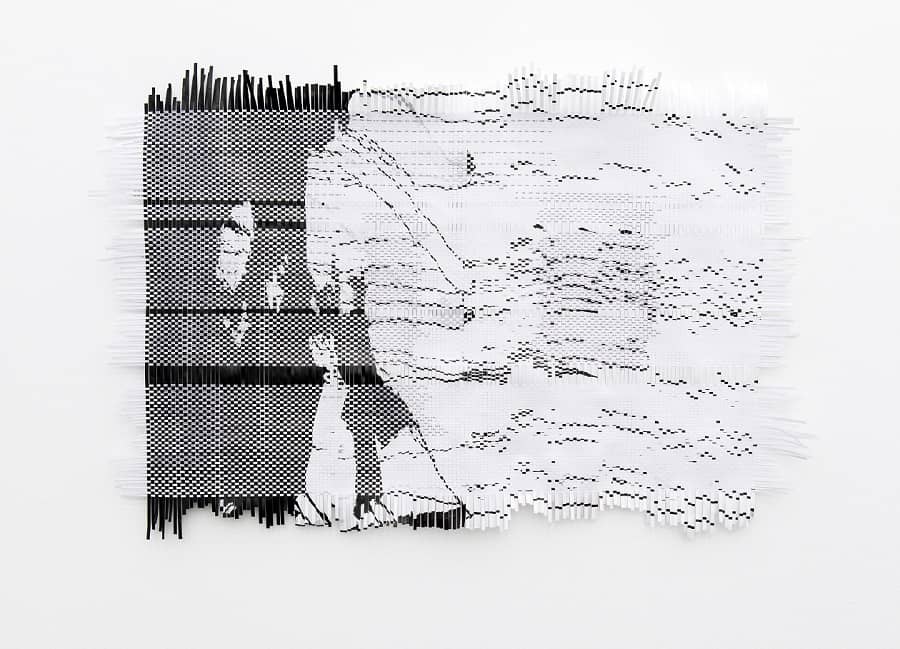

Damla Tamer: It would be my pleasure. Divination Objects is an ongoing series of paper tapestries that are made by first splicing then weaving together two distinct source materials: ink stain drawings and text compositions containing prompts from academic teaching evaluation surveys filled out by students at the end of university courses. The process of producing these materials was influenced by the ikat textile technique in which the horizontal and vertical threads of a rug are dyed before being woven in anticipation of a final pattern that emerges from the alignment and overlap of dyed areas. The particular future-investedness of this technique, with its organization of planning and anticipation towards an outcome, really interested me.

EDO: I’d like to explore how these two types of materials come together: the ink stain drawings and the teaching evaluations, and what each brings with them. This series was exhibited as part of The Artist’s Studio is Her Bedroom at the Contemporary Art Gallery in Vancouver. Curator Kimberly Phillips placed these works in the context of parenthood, remarking on the bodily nature of the works and their relation to gravity. Would you mind expanding?

DT: Sure. I understand gravity as a material force that directs the very processes of our daily lives, including our growth and decay. It makes possible the ability to hold food down and find our way onto our two feet. It is also a force that creates the weight through which our bones become brittle and our skin sags.

The particular ways in which material and social life forces influence, mimic, and conflate with each other, the very terms of their mobility, interest me. The ink drip is subject to gravity, but also ends up making a mark that exists on the flat surface of paper, in two dimensionality, as a stain. Text occupies a similar double-position in that it can be read linearly, sequentially, while also existing as blocks of shape—it can be read and interpreted as both language and outside of language.

EDO: And you’ve woven these drawings with teaching evaluations, which you’ve had to administer as a sessional lecturer. How do these evaluations relate to this sense of “future-investedness” through which you introduced the work?

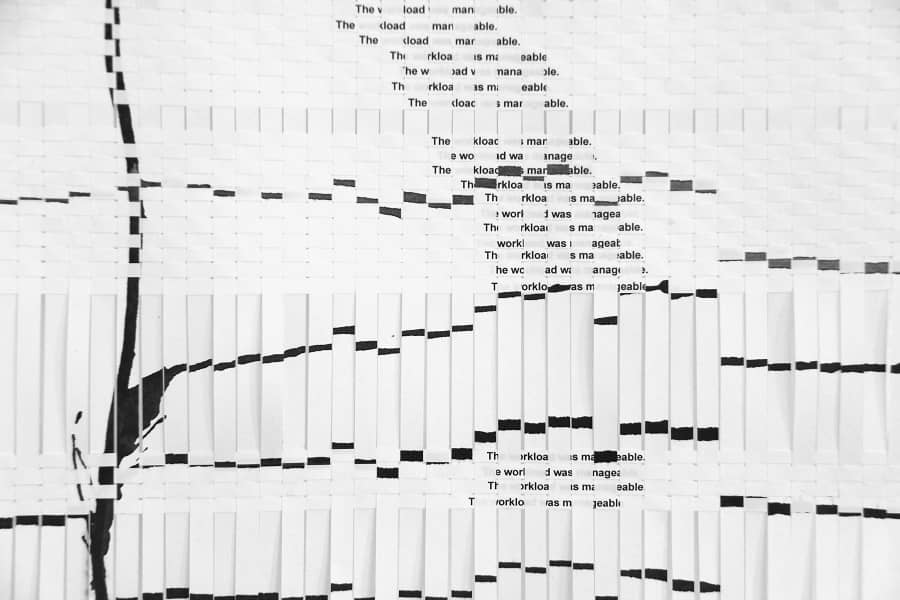

DT: I see the teaching evaluations as both symptomatic and constructive of a pedagogy that focuses on efficiency. Besides contributing to the labour precarity of contract workers in academia, they represent an atomized and risk-averse pedagogy at large. They reflect a certain attitude towards the future, a futurity, that is always predicated on precedence. Even uncertainty is absorbed into the making of “options” in this framework of precedence. While students, in an increasing way, are living with a sense of “no future” (rising living costs, ecological mayhem, but also the slow implosion of the economic structures that make up the university and a lack of permanent jobs after higher education), the grading of the teaching evaluations is offered as a way to patch up this dissonance.

The phrases used in these evaluations recast the temporality of learning as an idealistic timeline: “The instructor used class time effectively”; “Overall, the instructor was an effective teacher”; “The instructor made it clear what students were expected to learn”; “ I can see ways that content learned in this course will be useful for me.” These narrative statements create very particular relationships between cause and effect; intention, action, and result; creating closed loops that do not correspond to the factors of vulnerability, trust, and risk that learning encapsulates both for the teacher and the student. By presenting students with sentences to grade (in the form of choosing from levels of agreement), they reorganize the process of learning into a simplified timeline; by asking students how well their experiences have matched this timeline, they create a certain ideal that is cast as truth, normalized and objectified.

EDO: In terms of temporality, the title Divination Objects implies traditions of understanding the future through traces visible in the present. Are there other practices of foretelling that you are looking to as you create these works? How do you figure the present moment shapes these intuitive predictions?

DT: Yes! I’ll draw from my grandmother’s reading of coffee ground stains. In her fortune-telling, a deciphering of what is internal to the listener (what they may be thinking or feeling) and what is to come their way (an opportunity or danger, a “kısmet”) often merges. She has also never hesitated to include what she already knows from common conversation (which is supposed to remain “apart” from a practice of fortune-telling proper) into the contents of her coffee-cup reading. For example, last time she read my fortune, she mentioned a “big opportunity” coming my way; this was right after I had told her that I had received a new employment contract. It is this heterogeneous aspect of the coffee-reading, which is performed among family, friends, and neighbours, connecting known to unknown to known, and forging relationships between revealing and willing that has made me wonder what is possible beyond the iconographical analysis of marks in an artwork, a picture, a shape.

Parsing through image-based divination techniques and how these could inform our scholarly interpretation of images, Begüm Özden Fırat notes that, “The act of the fortune-teller is an act of subjective re-narrativization of the image that does not necessarily coincide with a preceding text.” Consciously encountering and re-encountering the details of the image, interpreting and even over-interpreting them, may result in a semiotic narrative that bases itself on the primacy of pictorial detail. This requires a consideration of detail-interpretation as more than a “subjective” extraction of meaning (which positions the consequence of the interpretive act as an effect that starts from but diverges away from the work and towards the person looking at it, as in the case of Roland Barthes’s “punctum,” which “pierces” its subject). Even if we appeal to a multiplicity of meaning in order to expand this process beyond the personal, the consequences of interpretation remain lodged in the gaps among the audience. In fortune-reading, however, the detail-interpretation returns from the subject back to the image to re-narrativize it, to re-semanticize it. This approach belongs fully neither to processes categorized as accident (particular) nor methodology (general), but starts and restarts with each new reading of the image, and of each other.

EDO: We are pleased to have also been able to include Bağırsak Düğümlenmesi in Issue 3.42 of The Capilano Review. Could you tell us a bit about it?

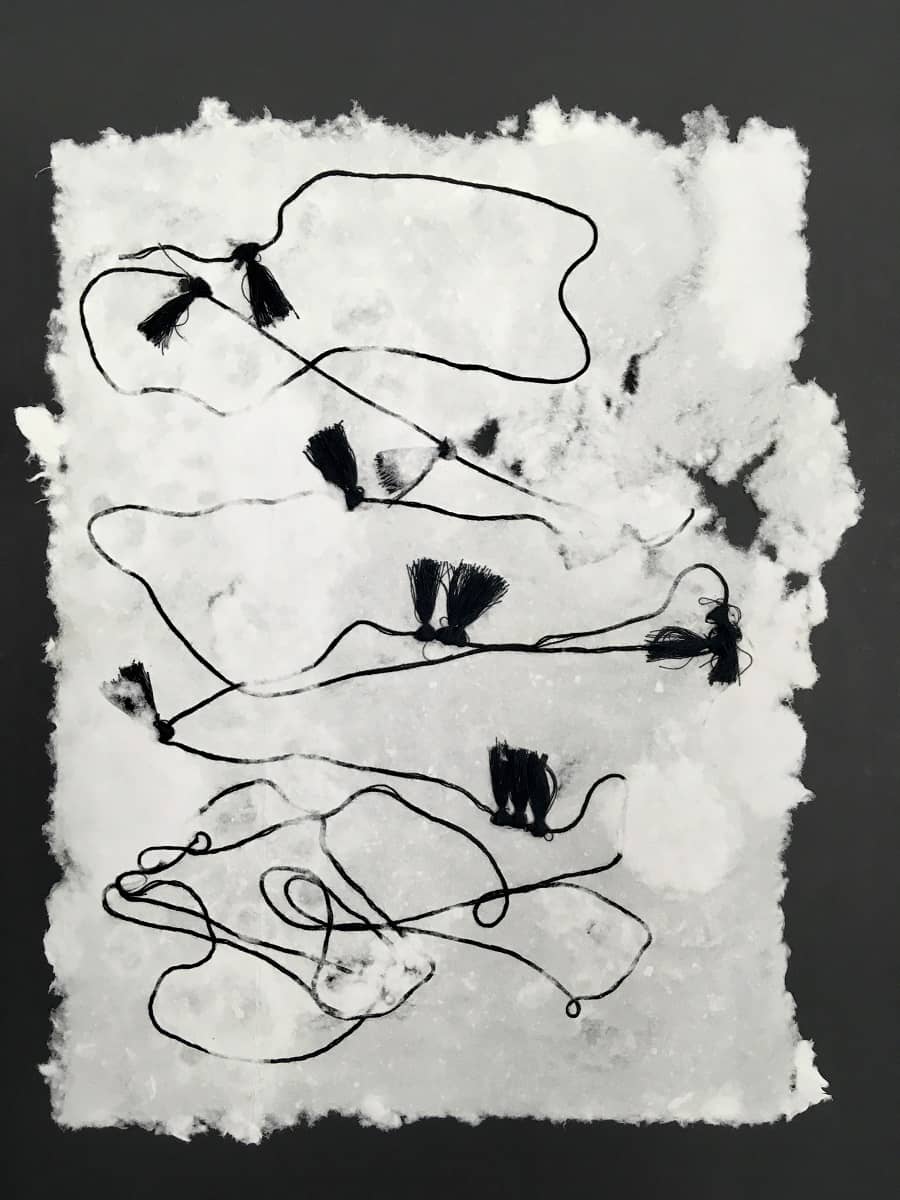

DT: Sure. Bağırsak Düğümlenmesi is part of an in-progress series, a handmade piece of letter size paper in which I embedded a trimming of thread and tassels. The Turkish title translates into English literally as “bowels-getting-knotted-up.” While the phrase describes a medical condition that causes obstruction of the bowels, the verb düğümlenmek (getting tangled up in a knot) is often assigned to body parts to describe imaginary lumps or knots in the body that result from anticipation bound up with terror or sadness.

I return to simplified representations of bowels for thinking about text, but also the growth of body cavities that allow us to eat, breathe and speak—both in the individual and the evolutionary timescale; the internal mechanisms of digestion, absorption, and ultimately abstraction of the material world with its incorporation into the self.

EDO: Your practice spans performance, mark-making, and textiles, as well as involvement in the Vancouver-based artist mothers collective A.M. (Art Mamas). The iterative aspect of many of these modes of working also support your artistic negotiations of political history. Would you be willing to share about some of the tensions this work explores?

DT: Another influence for the motif of bowels, which I will be exploring further with this body of work, is the twenty-four-hour “solidarity hunger strikes” held in support of Nuriye Gülmen and Semih Özakça in Turkey in 2017. Gülmen and Özakça began a joint hunger strike in 2016 after losing their respective jobs as an academic and a teacher (during the State of Emergency that lasted two years, hundreds of others were removed from their positions with a similar “decree law”). Gülmen and Özakça held their hunger strike first in public squares and later on from prison after being arrested on the charges of serving a terrorist organization. During the fourteen months of their strike, public opinion regarding the value of their chosen route of action varied greatly, especially among the supporters of their cause. While some deemed the hunger strike was too “symbolic” and did not contribute to a material outcome, others claimed it was a self-deprecating route of action that prioritized the individual over the collective. Others devised ways to support Gülmen and Özakça’s action, such as taking shifts to hold solidarity hunger strikes—which lasted short periods of time such as twenty-four hours—in public squares.

EDO: There seems to be an echoing approach across each of the projects you’ve mentioned. Your work teases at an integral tension between your specific and personal experiences (teaching evaluations and the specific hunger strikes) and the use of weaving and textiles for these specifics to enter an investigation of the semiotics of such experience. It seems to be putting into question the possibility of the sign to be read as symbol (such as the tassels as bowels, and resistance as symbol) or the sign to be utilized as structure (such as evaluations to be used as process, rather than statement). Are there other projects you are working on throughout this time?

DT: At the moment I am working on fragile weavings made of clear monofilament thread, clear bra straps, paper pulp, and possibly other materials as well. I am hoping to combine multiple panels to create a single hanging structure, a curtain of sorts. The materials for this work-in-progress are drawn from a brief memory from my early art-student years: the condemnation of the use of clear monofilament (fishing line) to suspend art works with because this material “pretended” to be invisible, much like transparent bra straps, while not being able to be so completely—a gimmick.

Courtesy of the artist with support of Canada Council for the Arts

I argue that the pedagogical impulse to demand a work to reveal its own mechanisms and be free of gimmicks partially rests on gendered assumptions about sincerity, transparency, and where the meaning belongs. The criticism of clear bra straps implies a demand on women to not only properly contain their body parts, but also be “honest” about the appearances of their containment, to account for them. Moving beyond this work, my preoccupation is how trust can be collectively restored without appealing to a classic understanding of sincerity that is bound up with the clarity of signifiers.

EDO: Damla, thank you so much for your generosity in sharing your work with us, and for the extensive consideration that has gone into these meticulous works.

Divination Objects by Damla Tamer is featured in Issue 3.42: Translingual (Fall 2020). Purchase a copy of the issue here or subscribe today to get this issue plus two more delivered to your door.