This piece originally appeared in Issue 3.8 (Spring 2009): Moodyville.

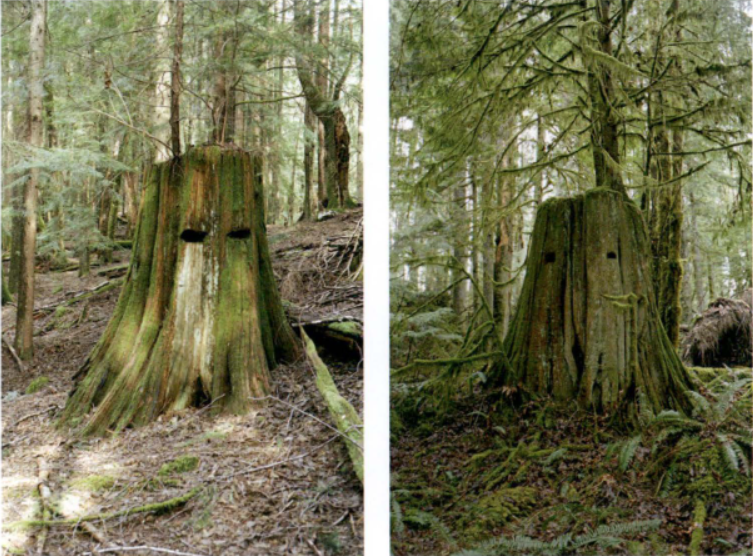

Every major forest, every massive multi-country forest in the world shows terrible scars from human contact, and each forest is scarred in a different pattern, by a different style of clearcut. Dan Siney’s series of photographs, Stump Skulls, depicts the pattern of the clearcut of west coast rainforests on the face of an individual stump. We think of deforestation on the scale of hectares. However, Siney focuses on the singular. The eye-holes in his photographs were made by nineteenth-century loggers puncturing old growth cedars to secure the springboards where they stood while felling the tree above. Siney has photographed the features of these old ghosts in old growth stumps near Moodyville, one of the more prosperous lumber towns on the west coast in the nineteenth century. More than a hundred years later, all that remains of BC’s rainforests is scarred, undead. Politics and business define the clearcut’s form, and a country’s clearcuts follow a pattern.

Veins. The northern half of the Democratic Republic of Congo protects the last of Africa’s primeval rainforest, and from high above the ground, with the whole body of the rainforest in your sights, the patterns of clearcut in the Congo look like thick varicose veins, or the veiny patterns of craquelure that form in dry oil paint that has been too close to the heat and too long in the sun.

Bones. Across the Atlantic, the Amazon rainforest in Brazil has clearcut scars that have been described as looking like the pattern of fishbone, they also look like the antennae on a hairy insect or the antennae on the tops of houses for tv reception. The clearcut pattern is a zipper, a skeletal cage, a scaffold.

Skin. British Columbia’s clearcuts spot the province like someone with a terrible skin disease, a severe staph infection or malignant discolouration. The surface looks like it’s being eaten alive. The forests of BC were once a vast living organism. Now the entire coastal forest is perforated and gridlined and riddled with hideous bald patches. Half the forest is gone, but from the sky, it still looks green through a pattern of holes, like a sponge. The checkerboard pattern is touted as ethical silviculture for a sustainable forestry practice, and this has spread down the entire Continental Divide.

Eyes. The photographer is looking for eyes. He is looking for the world’s ineluctable reflections of himself, of his people, the eyes of today and of the past. Deep in the forest he finds them. Dead-eye binoculars looking out at him from the stumps of history. They are damaged goods. Like many of his subjects, Siney’s view of the forest is sympathetic to scars. In his Standing Forest After The Rain, the sun breaks through the canopy and its light seems to be caught in a thousand beads along the fanning branches of a falling spruce. Each little drop of sun is the glowing cocoon of a tent caterpillar larvae that has spread its webs over the tree as thickly as cancer across a lung, devouring the leaves and bark as worm, and when it awakens as moth, it will defoliate whatever of the tree is left behind.

In nature and in the city, Siney is after an illusory sense of the spontaneous. Siney’s grainy naturalism shows forests to be less intact, less pristine, breaking up and being dispersed. He photographs change. His pictures always look for the dying part of us. A soulful loneliness in the forest and social anomie in the city. His pictures of people show scenes of unrest and random acts of flagrant self-expression — like the lumberjacks implied in his stump skulls and the radiant caterpillars in his forest. In many of his portraits of artists, punks, hobos, and outsiders, it will be a single pungent detail that immediately catches the eye, whether it’s an open wound or physical scars, and subtly, after that, you begin to see the social pattern his subjects inhabit. They are often familiar enough city people, unhealthy and androgynous, a complex weave of weakness, honesty, suspicion, mindfulness, and dysfunction.

Often in Siney’s photographs, there is an implied yearning for the return-to- nature, even in the most extremely city moments. A picture of a vase of daffodils is presented under the flashbulb of a camera going off inside the backseat of a sedan, or twentysomethings literally naked in the woods with bows and arrows, or leaping out of lakes or walking through steam, or tossing up a pile of leaves or feathers. The concept of scarification has historically been part of many cultures’ coming-of-age rituals, and the punk nuts and bolts pierced through the flesh of Siney’s younger subjects are reminiscent of the stump skulls as well, as though the camera’s eye was looking through these holes to find the human condition.

Our demand for lumber is one thing, the icon of the lumberjack is another. Besides the power of big business, there is the irascible genius of the lumberjack to consider. The identity of the lumberjack is tied to his nineteenth century roots as an antisocial creature, a private man isolated from the boons and boondoggles of proper society. Ironically, he has more in common with the forest. He is a hero to capitalism, because he is on the very breach of the vanguard, forging new territories for big business, and in his wake, new land for the open market. The lumberjack is a drug dealer feeding us our own death, and in his mind, he is more sympathetically bonded to the tree than the user. He is emphatically not a paper-pusher. The lumberjack of yesteryear, the woodsmen who encountered the forests of British Columbia in their prime, these were volatile men with anarchic instincts, that is to say, slightly feral, lovers of liberty, personal strength, survivalism, individuality, and raw isolation from society. The chaos of the natural world suits the lumberjack, he hears the ghosts of the world howling clearer than all the little twitters of civilization. How do you tell a man he can no longer stand on the skull of the world?