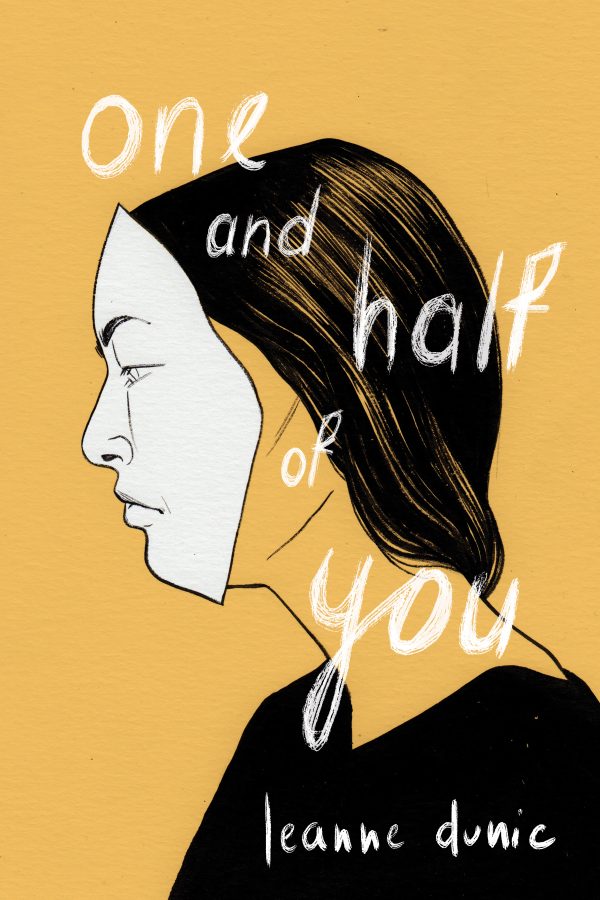

A promise is situated in the opening lines of Leanne Dunic’s second collection of poetry: “I will draw you some maps.” In One and Half of You maps reify the inhabited milieux of a biracial body and compose the textured gradients of Singapore and Vancouver as richly-storied places. Beginning in Brentwood Bay, Central Saanich, in a home across from the W̱JOȽEȽP reserve, Dunic’s poems evoke place and identity as a pair of second skins, forming a fabric upon each other:

As a child, I didn’t understand the history of

this and, that gathering clams and sea beans

from the shores was stealing.

While playing with her brother along the “ocean-bound creek,” a locale of childhood memories, Dunic observes a “movement between” fresh and saline waters. In turn, she perceives her own racial hybridity as one of many “birthmarks: some have vanished, but then/again, nostalgia distorts.” Nostalgia is an effect of vanishing according to Svetlana Boym’s interpretation in which she derives the feeling from “(nostos—return home, and algia—longing) [as] a longing for a home that no longer exists or has never existed.”1 In Dunic’s poetry, the definition of birthmarks transposes language, movement, family, and queer explorations of love. As coordinates mapping the memory of one’s body, these birthmarks can incite the nostalgic comfort of a home but also a heaviness in their absence and displacement that, as Dunic conveys, are like “mountains / I try / to move.”

For a poet ensconced in the betweenness of languages and a hyphenated identity, Dunic’s “movement between” spectrums of Chinatowns across the world attests to the yearnings of the body for a place it recognizes; however, these experiences are met with a lack of easy answers in the historic localities of any singular city:

I dwell in the Chinatowns of port cities.

Victoria, Vancouver, stints in Singapore,

Kobe, Yokohama, San Francisco, Seattle.

No answers, only red and gold plastic

decorations and the question, <Is your

mother Chinese?>

In Japan and Singapore, the disorientating effects of working with modeling agencies register deep and surface with labels: “never beautiful, only model.” In Victoria, the weight of carrying figurative “mountains” materializes into a double-consciousness, simultaneously “long[ing] to attend the Chinese Public School / on Fisgard Street” and “hop[ing] for my own whiteness and a prince to / take me to other worlds.” Alterity resonates in the place of heightened expectations. Dunic shows how the affects of a particular environment can evoke a hyperawareness of difference, more than a sense of ease and belonging. Nevertheless, in acknowledging Wayson Choy’s The Jade Peony and Wong Kar-Wai’s In the Mood for Love, she writes of finding “an invitation to / community I didn’t know I lacked.” Dunic thus discovers comfort in her meaningful encounters with poetry, film, and diasporic community makers instead.

Although most of Dunic’s lines are composed in English horizontally, the presence of a few Mandarin characters retained from childhood lessons map the page of one poem vertically from right to left (20-21). On the accompanying page where these characters are absent, their previous presence continues to occupy a gap as the poet is told, “We speak Cantonese, not/ Mandarin. / And now I speak neither.” Language, as a birthmark that comforts, fades, and distorts with time, simulates a connection that is further felt between lovers. Whether this language bridges a romantic partner, a sibling, or “lanky counterpart” reading on the bus, its gestures and specificity open up the spaces of a “hyphenated world” constituted of many people’s presences; each have appeared and left their marks on Dunic as “one and half of you.” Once apart, she discerns that “separated, our tongues fade.”

In concert with the drastically shifting face of Chinatown’s physical landmarks, the written and oral language that Dunic possessed as a child forms an additional fabric, wrapping and distorting around her perceptions of place. Her poems are a testament to how even a century-old establishment on Keefer and Georgia begins to forget once displaced of its roots. Interspersed with the rhythm of tourists’ flocking on sidewalks and the taste of pork, Dunic’s poems witness the events of permanent closures, rent increases, and fading photographs on the walls of restaurants. Against the ever-gentrifying calligraphy of Chinatown’s streets, Dunic’s poetry acts as a “love letter” to place at once past and present.

one and half of you by Leanne Dunic was published by Talon Books in 2021.

- Svetlana Boym, Future of Nostalgia, Basic Books, 2001, pg XIII. ↩︎