Ever since The Capilano Review celebrated its 50th anniversary last year, we’ve been thinking about the idea of legacy. In particular, we’ve been reflecting on what it means for a magazine to be a home to so-called “innovative” art and writing; how definitions of experimental practice have evolved over the years to include new manners and modes; and the kinds of editorial moves that have allowed, and might continue to allow, this work to flourish. Since its earliest issues, then, the Review has notably been a place to find art and writing side by side–a unique aspect of its editorial structure that reflects not only the 1970s ethos of “art as life” from which it originated, but also the energy of interdisciplinary collaboration that was so central to that period.

Ann Rosenberg joined The Capilano Review in 1974 (Issue 1.5), a few years after its founding. An artist, writer, art critic, art historian, curator, and faculty member of Capilano College’s Fine Arts department, Ann took up the post of TCR’s very first “Visual Media Editor,” shaping not only the early aesthetics of the magazine and the artists and artworks featured in it, but also deepening its editorial scope through the development of numerous special issues on artists and architects including Gathie Falk, Arthur Erickson, N.E. Thing Company, and others. Ann would continue at the magazine in various editorial capacities until 1986 (Issue 1.40), with an additional appearance in the collaboratively produced Issue 1.50 (1989) that celebrated the end of the Review’s first series.

Thank you to Dorothy, Jenny, and Pierre—three former editors of the Review and Ann’s dear friends, colleagues, and fans—for so generously sharing their memories of her with us for this piece.

—Jacquelyn Zong-Li Ross

Jacquelyn Zong-Li Ross

Pierre, could you talk about how Ann came to The Capilano Review?

Pierre Coupey

Well, she probably came in the same way that many of the other faculty came in as editors, as a consequence of the very controversial 3rd issue.

Jenny Penberthy

You mean the one with the cover?

PC

Yes. The cover. [Laughs]

JP

There have been a few controversial covers over the years . . .

PC

[Smiles] Well, as a consequence of that issue and that cover, I had to write a constitution for the magazine. I had to involve more faculty and more students, and to broaden the base of the editorial direction of the magazine, so that it wouldn’t be entirely me being an uncontrollable wild man, which is of course what I wanted to be all the way through with The Capilano Review . . . [laughs]

JP

Was Ann already on faculty at that point?

PC

Yes, she was already on faculty, so of course we knew each other as colleagues and enjoyed each other’s company a great deal. The original intention was to have editors of the magazine come primarily from the English Department, so to have somebody from outside the department (in this case the Art History department, or what was then called Fine Arts) might have been more difficult to get through the Humanities Division, I don’t know. At some point I asked Ann if she would be willing to join us, and she certainly was.

I always remember Ann as one of my favourite colleagues at Cap because she was so companionable. She was a true person. She had integrity, she was obviously smart as a whip, and she was extremely kind. I can go on about Ann’s qualities if we want to get into her as a person, but in terms of her coming in as Visual Media Editor, well, she was the one who started the Art History Department at Cap, and she was the one who brought in Josephine Jungić,1 who was such a star person in that department and in the division as a whole.

JZR

Revisiting some of the issues that Ann was involved in over the years, what strikes me most is the seriousness with which she went about the task of “visual media editing.” She was genuinely immersed in the practices of the artists she was working with. Some of them I suppose she would have considered her friends and colleagues. But she also seems to be someone who was driven by a strong curiosity about the work that they did. She took very seriously the role of publishing this work and making space for it.

PC

Ann knew her stuff, not only as an art historian, but, as you say, she had a deep curiosity about what was happening in the art scene in Vancouver at the time. And she had friends throughout the art community: she was very close friends in particular with Gathie Falk, who has just celebrated her 95th birthday. She had a particular interest in artists who were slightly outside the mainstream, the unconventional artists, and perhaps even outsider artists—people who, like Jerry Pethick, took different directions in the art world, and also, in effect, challenged the art world itself rather than trying to ingratiate themselves with it and integrate with its norms. In that sense, I think Ann was always a bit of a nonconformist—always interested in the unconventional, always interested in the independent mind. That was a quality she reinforced in The Capilano Review.

Dorothy Jantzen

That’s a really good summary, Pierre. I like that. We could stop now. [Laughs]

At the beginning, or until TCR left Capilano, I think all of the editors were Capilano faculty or students. You had to be a faculty member to be an editor. So I arrived at Capilano a year later, and, as far as I know, Ann was the first Art History—what was then called Fine Arts—instructor at Capilano. She put a very high value on local art and local artists. That was what she wanted to feature—that’s what she was interested in teaching and mentoring and fostering—and she thought it was important that the world—or at least, Canada, at least Vancouver—see those artists up front.

We also mustn’t forget her involvement in The Warehouse Show—that was part of her commitment to the local art scene. That was in the ‘80s, wasn’t it Pierre?

PC

Yeah, I remember roughly it was in the ‘80s.

DJ

After the initial October Show, Ann became one of the curators of The Warehouse Show.2 I don’t remember whether her involvement continued into the later Artropolis shows, which were rather more formal and almost institutionalized in comparison with the earlier shows. The Warehouse Show was held in what was a disused warehouse, essentially. Ann was part of the small committee of curators who put that show together, and she was a definite mover. So it was like a salon des refusés, you know . . . the artists who were being neglected by galleries and so forth. Every floor of the building was full of this art. It was wonderful to walk around.

JP

It was incredible.

PC

Perhaps they were precursors to all these art crawls?

DJ

Yes, that’s right.

JP

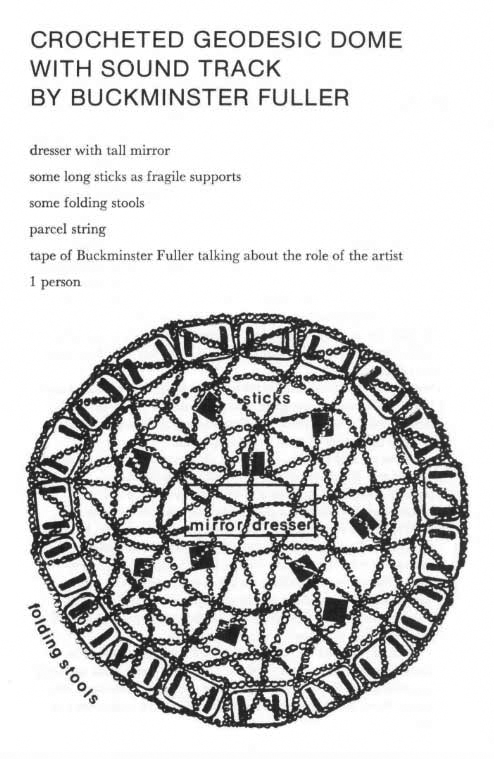

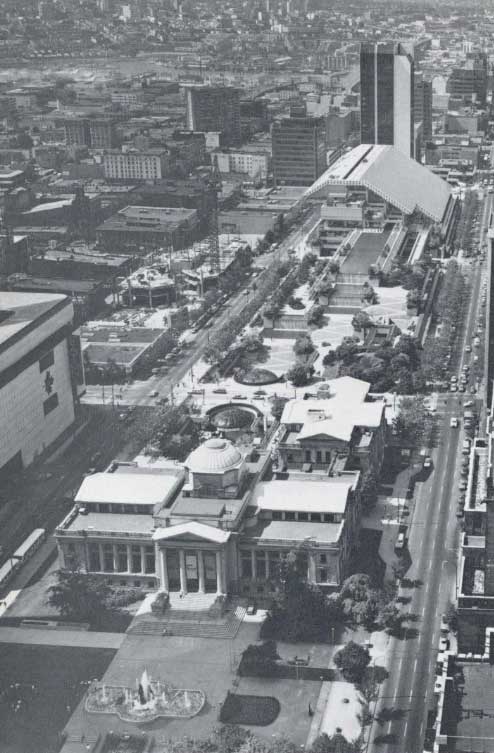

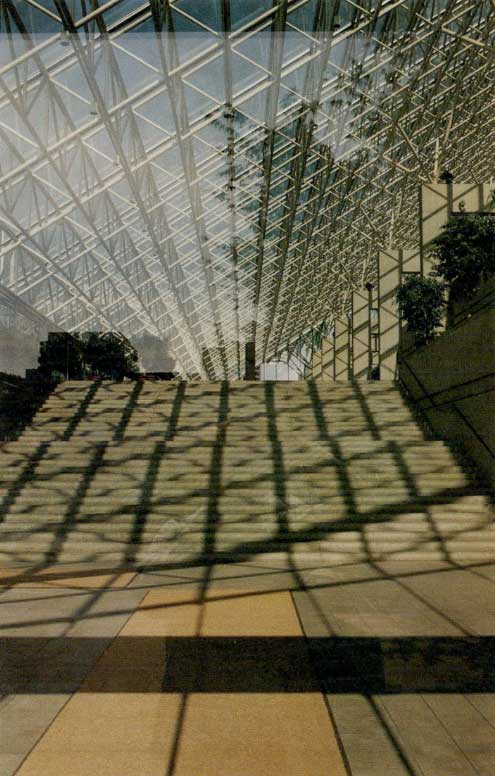

I was looking back at the Gathie Falk issue last night, Issue 1.24/1.25, and at that piece in the second volume of the performance works, Gathie Falk’s “crocheted geodesic dome.” [Laughs] I think the piece may well be referencing the Habitat conference in Vancouver, the United Nations Conference on Human Settlements held in 1976, which I saw when I first arrived in the city. The iconic structure, even the symbol of the conference, was the geodesic dome popularized by conference celebrity Buckminster Fuller. What a fascinating riposte for Gathie Falk to crochet a geodesic dome—inserting the feminine, considering the utility of the dome, opening it both to critique and to humour. It reminds me how useful it is to historicize these early issues of TCR. You also raised the question, Jacquie, in some of our earlier correspondence, of “Why Arthur Erickson?” in regards to another special issue of Ann’s, Issue 1.40, on Robson Square. Vancouver’s Arthur Erickson was front and centre of local consciousness in that period with his designs for the recently built SFU campus, the Law Courts and Robson Square downtown, and the Museum of Anthropology at UBC. Our world-renowned architect delivered the essence of modernity and innovation. And so, given Ann’s desire to promote the local, what could be better than a close focus on Robson Square?

PC

Well, yeah, you bring up Buckminster Fuller, and of course the figure behind Iain Baxter is Marshall McLuhan. Both McLuhan and Fuller were very important seminal thinkers everyone was paying attention to at that time. But the other thing you touched upon is bringing the feminine in. Certainly Ann was a feminist. It was very important to have that voice in the magazine.

JP

Ann was a quiet presence and guiding intelligence across a full twelve years of issues.

JZR

It’s interesting to hear you speak about Ann’s Vancouver-centrism and the place-based nature of what she was interested in doing with TCR’s platform. Her writing is quite journalistic or reporter-like, in a way; her issues have a very specific, descriptive quality. I mean, she essentially treated some of these art sections and special issues as artist monographs! Images followed by long descriptions of each work, almost documentary in nature . . . She was really trying to get these artists on the map. I think this is at its most extreme in the Robson Square issue—which, by the way, I was just remembering, was published in 1986, the year of Expo ‘86 but also Vancouver’s centennial year, in which I can assume there would have been a lot of conversations going on to the tune of, “What is a city?”, “What is city pride?”, and so on. I think at her most extreme in that issue Ann really brought a kind of civic, pedestrian-level energy to the activity of art history. What were these places that we were walking through, she seemed to be asking, artists and commoners alike? What did they look like, feel like, from the street?

JP

Jacquie, I love your point about that issue addressing the pedestrian-level in relation to this visionary modern structure. Ann is so conscientious. She goes to the Arthur Erickson office, interviews and talks to people in the office. Robson Square is a new way of thinking that she must fathom. Along with the design, there’s an extraordinary attention to the technical. You were talking, Jacquie, about the level of detail in that issue, and it’s interesting to see what she attends to. Yes, the pedestrian point of view, but also the behind-the-scenes views, the architectural drawings . . . she includes these in the issue, identifying the process behind the finished structure.

JZR

Do you think that sort of attention to detail and to the thinking behind the making of a work came from her lived relationships and friendships with artists—her views into their daily processes? Or did it come from her practice as an art historian, wanting to get it all right, for the historical record?

PC

Dorothy was closer to Ann as a personal friend than I was, but I would probably see it from the art-historical point of view. One of the things that Ann brought to her practice as an editor for the Review was that thoroughness, and that descriptive and personal-narrative approach to things. I mean, when you go through that section on N.E. Thing Company, it’s almost like she’s taking you for a walk through each element and each piece. In the Gathie Falk as well. She’s telling a story. She’s interested in how things came about. That was probably also part of her practice as a teacher, explaining things like this to her students. Do you think so, Dorothy?

DJ

Oh, yes, I do. A couple of times we’ve also raised the issue of what she meant when she called those five issues “killers,”3 right? One thing they have in common is that, yes, they were very complex and detailed—a lot of work. But two other things: first, nothing was too much work for Ann. Never. If it was in the service of art it was all just . . . what you do. Right? But “killers” meant something else to her as well, and it had nothing to do with work, or the amount of work that she as an editor had to put in. It meant for her that the pieces she was focusing on were important—were powerful. That they said something that nobody else was saying, at least locally. It was her biggest compliment. “That work is a killer,” she would say, meaning that it was a powerful subversion of the prevailing social norm.

PC

Very much so, yes. It was always a tough thing, which we all know as editors: there enters a spectrum of things you can put into any given issue, and you’re not including at least ten, or twelve, or thirty things, and then allowing this one thing in. So when you bring up a figure like Glen Toppings . . . There were at that time a whole group of artists who were I think parallel to Gathie Falk: Glen Toppings, Dallas Selman, Gary Lee-Nova . . . But Ann was very selective about who would be the most necessary to pay attention to, even though there were many other people the magazine could have paid attention to at that time. There were all kinds of people coming up in the photoconceptual world that we didn’t pay much attention to.

JZR

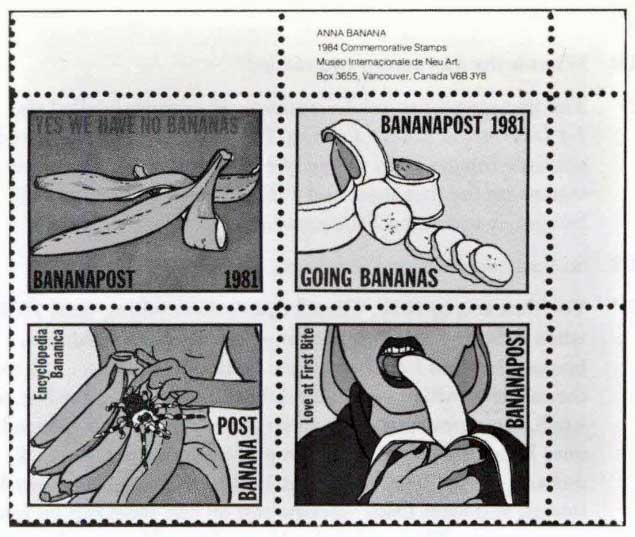

From an art historical standpoint, one issue I recently discovered in our archives is Issue 1.29 from 1983, an issue called “Surrealism? B.C.” Ann focuses this issue on the work of the west coast surrealist artist group Melmoth Vancouver,4 whose members included Ed Varney and others. She historicizes and contextualizes some of the things they were interested in in her short introduction—the interplay between eastern mysticism and hallucinogenic drugs, and so on—but then the issue moves directly into a set of profiles of each contributing artist. While arguably “surrealist” in one fashion or another, the artists she surveys are wildly different. So, again, there’s this evenness of curiosity and treatment. This issue is another example of her connecting what was of course a wider international Surrealist movement to the very local—trying to recentre Vancouver within these larger art world conversations.

JP

I love the introduction to the last issue of the first series, Issue 1.50, and one of the things that struck me reading that again is the role that she played in the design of the magazine. As she says in this introduction, she “became increasingly involved in the overall design.” She dedicates her section of the issue to the printer—Ron Smith of Morriss Printing.5 I think it’s fascinating that she does that. She acknowledges the crucial role of the printer! [Laughs] Integral to the design process.

DJ

Well, we didn’t do it electronically then.

PC

Exactly.

DJ

We did literal paste-up. We cut things out and pasted them down. But we knew that we could count on that particular printer to interpret our messy paste-up jobs in the clean, design way that we wanted. That was a lot of work for every single issue.

PC

I always went over to Victoria to meet with them, and went through every page with them . . .

DJ

Absolutely!

PC

And then we got a blueline . . .

DJ

Yes, a blueline. [Laughs]

PC

So yes, it was a long process putting an issue together, not done digitally. There was the overall design that Bob Johnson gave to us for the beginning of the Review, but then each issue had to be meticulously designed within that template and, yes, Ann did a marvellous job with that. There was a lot of material, it was very hands-on.

PC

One thing that we haven’t mentioned is that Ann had a great sense of humour. She was funny. I mean, she had a cigarette going all the time. We smoked like crazy in those days, even in the office, which drove other people crazy, and Ann would punctuate her jokes with a wave of her hand. Ann had a great laugh, and it was often sardonic. She didn’t put up with any bullshit.

DJ

None.

PC

Ann was very grounded, very straightforward, very direct, very honest, very frank. She would look you right in the eye and call you out, one way or the other, if she had to, or felt you needed it. She was also a very sensitive soul and one of the things I sensed of Ann as a person was that there was a wound in Ann. I think art was deeply necessary to her. It was not something frivolous to her—it was essential. It went to the root of her. Art was her way of working through and remaining a whole human being.

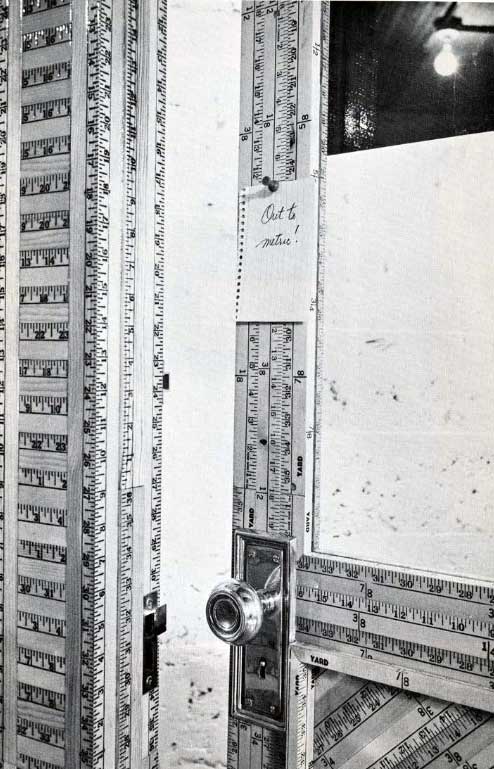

I also think it’s important to note that in that big double issue, Issue 1.8/1.9 (Fall 1975)—which was formally my last issue—I mean, that was a monster issue, with the Iain and Ingrid Baxter section. Right? That issue was about 400 pages! Now that was a killer issue! We not only had a big section on the N.E. Thing Company, we also had the sculptures of Roland Brener, Gary Lee-Nova’s thumb rule sculpture, photographs by Michael Agrios, we had Vickie Walker, Mr. Peanut for mayor from the Western Front, and we had Claude Breeze and Judy Williams. There was a diversity in that issue that goes beyond the Baxter section. Ann and I worked as a team on that issue, some were things I pulled in and some were things she pulled in. When I was compelled to broaden the editorial model, when other faculty came in as editors—visual media, poetry, prose—Daphne Marlatt, Bill Schermbrucker, Maria Hindmarch, Sharon Thesen, student editors—I wanted the other editors to have a great deal of freedom. I wanted them to have the autonomy to search for the work they felt important to bring in. It was an opportunity, in other words, for The Capilano Review to be in one way a successful continuation of what should have happened with The Georgia Straight and didn’t. There was at that moment a continuity in terms of where I was going with the magazine and how I wanted things to work.

JZR

I think at one point Ann described your exit from the Review, Pierre, as a “swift dive into the swimming pool.”6

DJ

Part of the mythology! [Laughs]

DJ

I also wanted to emphasize one other thing about Ann. When I was the Assistant Editor for her, she took me around to the studios of so many local artists. She knew them all. I had the sense that she knew every artist in Vancouver. She personally knew the people that she was publishing. If she didn’t know them beforehand, then she got to know them personally in the process, so that by the time she was publishing them, they were personal friends. We also went to a couple of the islands to see artists’ studios. It was a wonderful, wonderful part of it for me, when I was her Assistant Editor.

PC

I wish I could have been her Assistant Editor.

DJ

It was really great, Pierre. The thing is, they all welcomed her. They all knew her and were dying to see her. It was like coming home, in a sense. And I was welcomed too—absolutely—any friend of Ann’s, that kind of thing.

She was also an art writer. She would write art—I hesitate to use the word criticism or description or analysis—but it was for the semi-popular press, not just for literary or academic journals. She did real, and really important, reviews of local artists for publications like the Vancouver Sun.

JP

The language of some of that writing is quite strident and confident in its quirkiness.7

DJ

Ann never needed an editor or an English teacher to correct her writing. Never. That’s her own style. She also published two novels with Coach House.8

PC

Yeah, that’s something I’d forgotten.

JP

Incredible.

JZR

And wasn’t Ann also an artist?

DJ

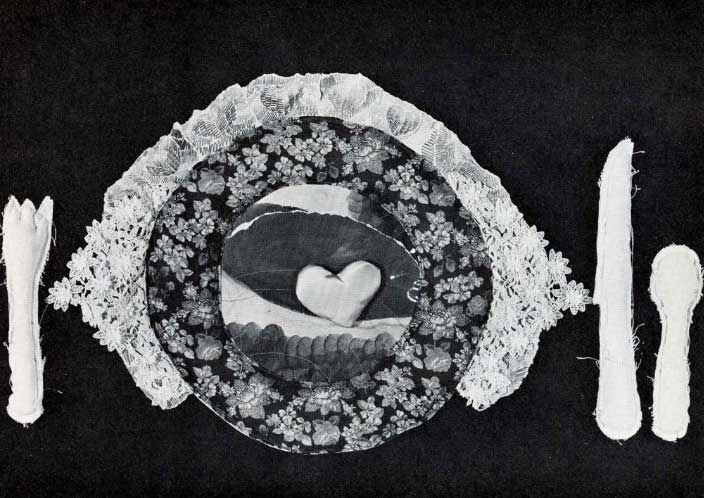

Yes. She had a few shows. I think it was probably what she valued more than anything else, but it wasn’t her greatest success, as far as she was concerned. She worked with pencil crayon—tiny, intricate drawings . . . full-colour, minute, complex. Once when I moved to a new apartment—I think this would have been in the ’90s—she asked if she could do a mural on the powder room wall. She would just drop by with her pencil crayons and paint . . . [laughs] She transformed that bathroom. It was intricate beyond belief. It took her months.

JZR

That she was also a writer and an artist herself was something that I had already sort of suspected, somehow. That kind of obsession with the thinking-behind-the-thing . . . There’s a real sensitivity in her writing and editorial style, an alertness to the long strand of decisions that eventually results in a final work of art. She seemed committed to tracking those kinds of invisible gestures.

PC

Ann brought that kind of long look into the magazine. She also built the structure of the special issues into the DNA of The Capilano Review. Some of it was there incipiently in the 1.8/1.9 issue, and also in Issue 1.4, when we started doing interviews and special sections on artists.

JZR

It’s interesting too because those special issues continue to be some of the most notable ones in the magazine’s history, ones we continue to return to, for reading, for pleasure. They really are quite unique.

PC

Well, TCR was never a free-for-all grab bag of what came over the transom. We wanted the magazine to go deeper into the material, deeper into what artists and writers were making.

JP

I was struck this morning, returning to that introduction for Issue 1.50—the final issue of the 1st series—where Ann says, “Pierre, now the magazine’s 5th editor, had called a meeting to plan the 50th issue. He has accepted a challenge to alter The Capilano Review’s direction and format. I wish him success and raise a toast to the journal’s new future.” Ann goes on to write about how she hopes for “continuity through change—that the magazine will still be interdisciplinary and in search of innovative work . . .” And what struck me is, okay, so this is what happens at the end of a series. The 3rd series is going to come to an end later this year, and I fully expect that the editors will be thinking about a new direction.

JZR

Yes that’s right. And particularly as The Capilano Review’s fiftieth anniversary has now drawn to a close and we begin to look ahead to what the next fifty years might hold, I’d say that one element of Ann’s legacy that Deanna Fong and I are especially keen to centre in future issues is this manner of deep engagement: with artists and writers, yes, but also and maybe even more importantly, with their material processes, thinking, contexts.

I’m grateful to all of you for sharing this history with me and for the opportunity to put our conversation in writing. It’s a small start to getting some of the underrecognized figures in our magazine’s history on the record.

Erratum: This piece, published online on February 28, 2023, was amended on March 22, 2023. The conversation has been updated with additional information. Special thanks to archivist Anna Tidlund for her assistance.

Pierre Coupey was a founding co-editor of The Georgia Straight in 1967 and the founding editor of The Capilano Review in 1972. He was Editor of TCR from 1972-1975 and again from 1989-1991, from which highlights included the special issue 1.50 (Spring 1989) to end the magazine’s first series, and Issue 2.1 (Fall 1989), a special issue dedicated to West Coast assemblage art. In the years since, he has served as a Contributing Editor and member of TCR’s Editorial Board, and continues to take a deep interest in the magazine’s focus, design, and survival.

Dorothy Jantzen was Assistant Editor of The Capilano Review from 1976 to 1984, including the period of Ann Rosenberg’s editorship, and Editor from 1985 to 1988. She learned everything she knows about art in Vancouver from Ann.

Jenny Penberthy is a former editor of The Capilano Review (2005-2011, 2014) and a current board member of the Capilano Review Contemporary Arts Society. Jenny never met Ann but in her time as editor she was drawn to the issues Ann edited as among the magazine’s most venturesome and fascinating.

Jacquelyn Zong-Li Ross is a writer, critic, and the current Art Editor of The Capilano Review.

- Josephine Jungić taught for thirty-five years in the Art History Department at Capilano College, from 1973 to 2008. Her scholarly publications include Giuliano de’ Medici: Machiavelli’s Prince in Life and Art (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2018). ↩︎

- Originally organized in reaction to the perceived exclusivity of the Vancouver Art Gallery’s plans for a large survey exhibition entitled Art and Artists: 1931–1983 celebrating the opening of the VAG’s new facility at 750 Hornby Street, The October Show of 1983 (held at 1078 Hamilton Street) and The Warehouse Show of 1984 (held at 522 Beatty Street) featured the work of over 120 and 190 artists respectively. A series of Artropolis exhibitions followed from these events, held at the Roundhouse, the closed and empty Woodward’s department store, and CBC Vancouver in 1987, 1990, 1993, 1997, 2001, and 2003. Ann Rosenberg was Chief Curator of Artropolis (1990), served on the Board of Directors for Artropolis (1993), and contributed as Editorial Consultant on Artropolis (1997) and as a member of the Advisory Board for Artropolis (2001). These events are archived in the Artropolis fonds held at UBC’s Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, the contents and description of which can be found here and here. ↩︎

- In Ann’s preface to her retrospective section of the 50th issue, Issue 1.50 (Spring 1989), she writes, “I am most proud, in retrospect, of the projects which were the killers: the N.E. Thing Company (issue #8/9); “Wood Sculpture of the Americas” (issue #12); “GLEN TOPPINGS remembered,” (issue #13); Gathie Falk Works (issue #24/25); and Robson Square (issue #40)—but which had to be done.” ↩︎

- Melmoth Vancouver also existed as a magazine, and prior to that, as The Vancouver Surrealist Newsletter. ↩︎

- As Ann writes in her section’s introduction, “When Bill Schermbrucker took over as Editor with issue #10, I became increasingly involved with the overall design and sometimes accompanied him to Victoria to finalize the layout. This was my introduction to Dick Morriss, the industrious proprietor of Morriss Printing, and to his chief assistant, Ron Smith. “Smitty” always took great care with the magazine’s appearance. My section of #50 is dedicated to his discerning eye and meticulous service.” ↩︎

- Ann writes, “Pierre’s resignation from The Review in 1976 was a shock. His challenge to keep the magazine alive was underlined by his swift dive into the swimming pool behind his house.” ↩︎

- One notable headline of Ann’s for a feature article on the N.E. Thing Company for the Vancouver Sun, dated September 8, 1967, reads, “Iain Baxter Is Pushy and Aggressive, But He Has Talent, And He Is Important Now, And Will Be More So If His Ideas Keep Coming.” ↩︎

- Both of Ann Rosenberg’s novels, The Bee Book (Coach House, 1981) and Movement in Slow Time (Coach House, 1988), are now out of print. ↩︎