Atheana Picha, May, 2020, watercolour and gouache on paper, 22.4 × 28.4 cm. City of Burnaby Permanent Art Collection, courtesy of the Burnaby Art Gallery.

Emily Dundas Oke

I thought we could begin with introductions. I’m Emily Dundas Oke and I’m a curator here in the Lower Mainland. I’m Nehiyaw, Métis, Scottish, and English. My ancestral connections are linked to Saddle Lake in Treaty 6 Territory and I’ve been living on the coast for about six years now. I’m continually humbled by the generosity of artists that I meet. It’s really the networks of artists – the collaborations, the support that I’ve received – that have kept me here. I’m humbled to be in conversation with the two of you.

Aaron Nelson-Moody

I’m Tawx’sin Yexwulla, or Aaron Nelson-Moody, and I’m from Squamish Nation – originally from a place called Ch’iyakmesh in Upper Squamish. People call me “Splash.” I live here in X̱wemelch’stn, or Capilano Village, on the North Shore now. I’m Squamish, and Scottish as well. I’ve worked in a variety of media, all around storytelling, and for the last thirty years have been digging more deeply into my Coast Salish history and into Coast Salish expressive cultures.

Atheana Picha

I’m Nash’mene’ta’naht. My English name is Atheana Picha. I’m Kwantlen and iTaukei, or Indigenous Fijian. My grandmother was from Tsartlip on Vancouver Island, and my dad is Irish, English, and Czech. My last name is Czech. I’m an interdisciplinary artist. I’ve been working with Splash since 2018 and it’s been really fun. I’ve also been working with Debra Sparrow on and off since 2020. I live in Richmond, BC.

EDO

How did you two come to know each other and begin working together?

AP

I first met Splash at Langara College. I decided to take Splash’s carving class because I’d always wanted to do wood carving, and after that I just kept pestering him. I’d be like, “How do I carve a canoe?” “What are the logistics of carving a totem pole?” “How do I carve this?” “What’s the best wood for that?” Then later, “Tell me all the Salish stuff!” He gave me this manila envelope with broken-down forms in Coast Salish work – “Coast Salish design language,” he calls it. I really like that term because it’s so fitting. Then I just kind of kept up. I really struggled picking up Coast Salish design because it’s very, very different, design-wise, from Northern stuff. It seems like it’d be easy, but it’s actually more complicated by being less complicated . . .

ANM

How we met: Atheana joined my Indigenous wood-carving class at Langara. It was a bit of a weird call to be hired for a position like that in a public space – I don’t even think they knew exactly what they were asking for – and we were kind of figuring it out as we went. But my elders in the Squamish Valley were really concerned that a lot of our youth were living away from community. They wanted to make sure that we went to public school so we could make contact and help bring people home.

So Atheana would show up – a really strong student, really determined to learn – and after class she’d be waiting very patiently with this little piece of paper while I was talking to students as they were leaving, and she’d say, “Can I ask you a question?” and she’d unfold the paper. There’d be a bunch of questions on the front, and then she’d flip over the paper and there’d be a bunch of questions on the back. So I’d be texting my wife saying, “I’m not going to make it home for dinner anytime soon . . .” [Laughs]

I started inviting Atheana to participate in events outside of the school. We can’t really shoehorn our culture into that building, and I don’t think we should have our culture only live in an academic setting. So I started to introduce her to people who I thought might be helpful to her. She met my mentor Xwalacktun and he put her to work right away on a big totem pole. So she got to hang out with 150, 200, years of carvers . . . all these older carvers just standing around watching her work. [Laughs] No pressure! But yeah, it was really good to meet Atheana. It would have been a shame if there weren’t public programs, because it would be much harder for students like Atheana to engage in community without that connection.

EDO

I feel like this is related to a concept that you shared prior to this conversation, Aaron: the idea of “two-eyed seeing” and how it relates to the different institutional, commercial, and community contexts that you navigate.

ANM

Two-eyed seeing is used a lot in Indigenous curricula, or Indigenous programs, as a way of not polarizing the world. It’s an intercultural or bicultural way of seeing. We’re often asked to pick a side – to be either totally traditional or a total sellout – but I think there’s room for something in between, where we’re still cultural but also trying to navigate a changing world. Two-eyed seeing is a way of reflecting that intercultural view of the world.

Historically, as artists, we didn’t have to pay so much rent, or pay so much to travel around our territory. We do need to make money – we’ve always sold, and we’ve always done things on commission – but it doesn’t mean we have to give up on community, and it doesn’t mean we have to give up on each other. We’re all struggling to find a balance. I don’t see the people who are talking about culture in a more rigid way in the outside world very much. You know, they’re not the ones doing the work in schools. I talked to someone recently who basically said, you know, “Screw anyone who doesn’t live on reserve, they made their choice” – he just had a very dismissive attitude towards all of our relatives who can’t stay at home. Squamish people . . . fifty percent of our population live off reserve. So that’s a lot of people to say “screw it” to. On the other hand, we have people working for galleries making a ton of money who often act terribly; they’re not really welcome in their own communities for all the bad behavior they have. They’ve sort of abandoned community and culture, and monetized aspects of our culture and are getting quite successful at it.

There are lots of people who tell us what to do or how to do it. But Atheana represents the first generation that’s a little more free from residential school abuse. She’s still dealing with the legacy of it. But in my generation, it was common to experience real violence in school, and the community was still reeling from people who had been through residential school. We’re hoping that we’re a little further from it now, but with all this newfound freedom comes a bunch of decision-making that my generation didn’t necessarily have to engage in. Atheana’s plugged in to the entire world now. I doubt it’s any less stressful, but there are different stresses that she’s navigating.

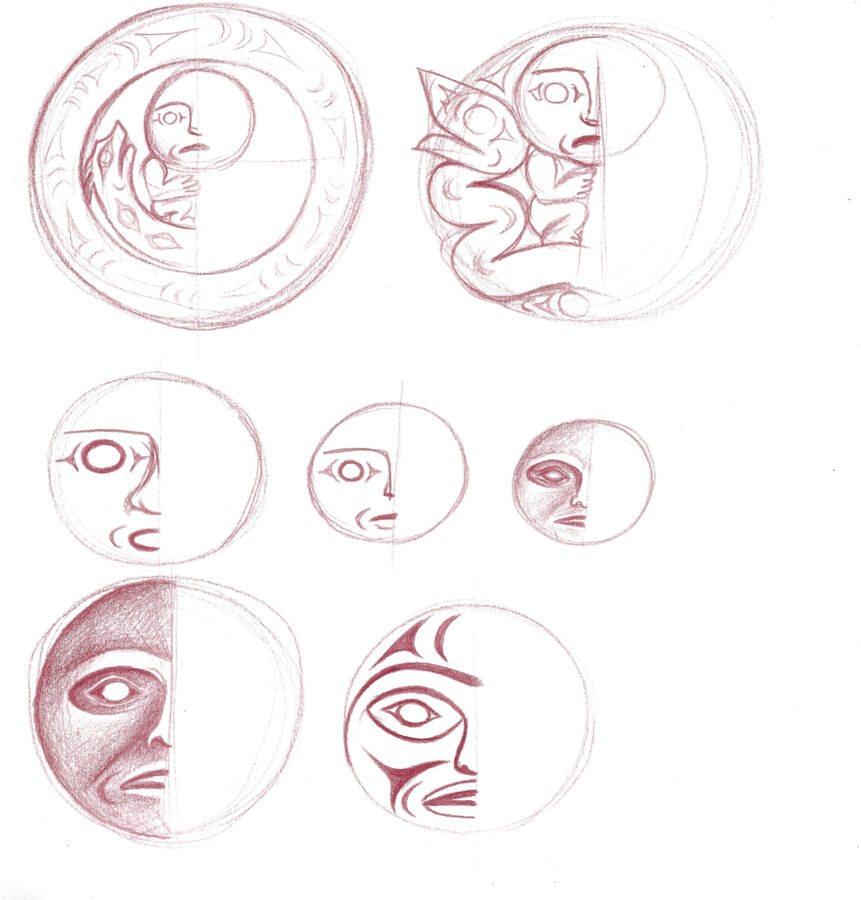

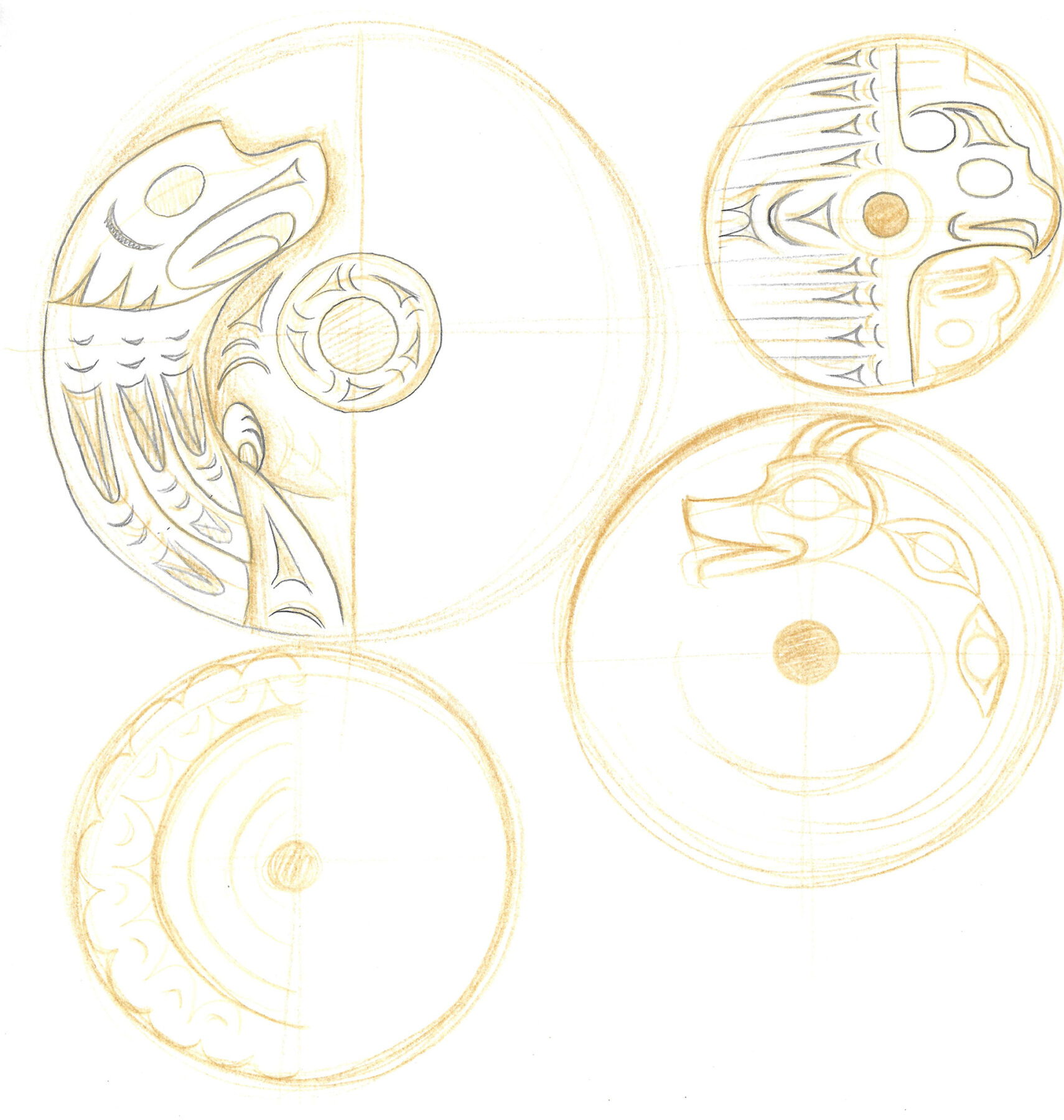

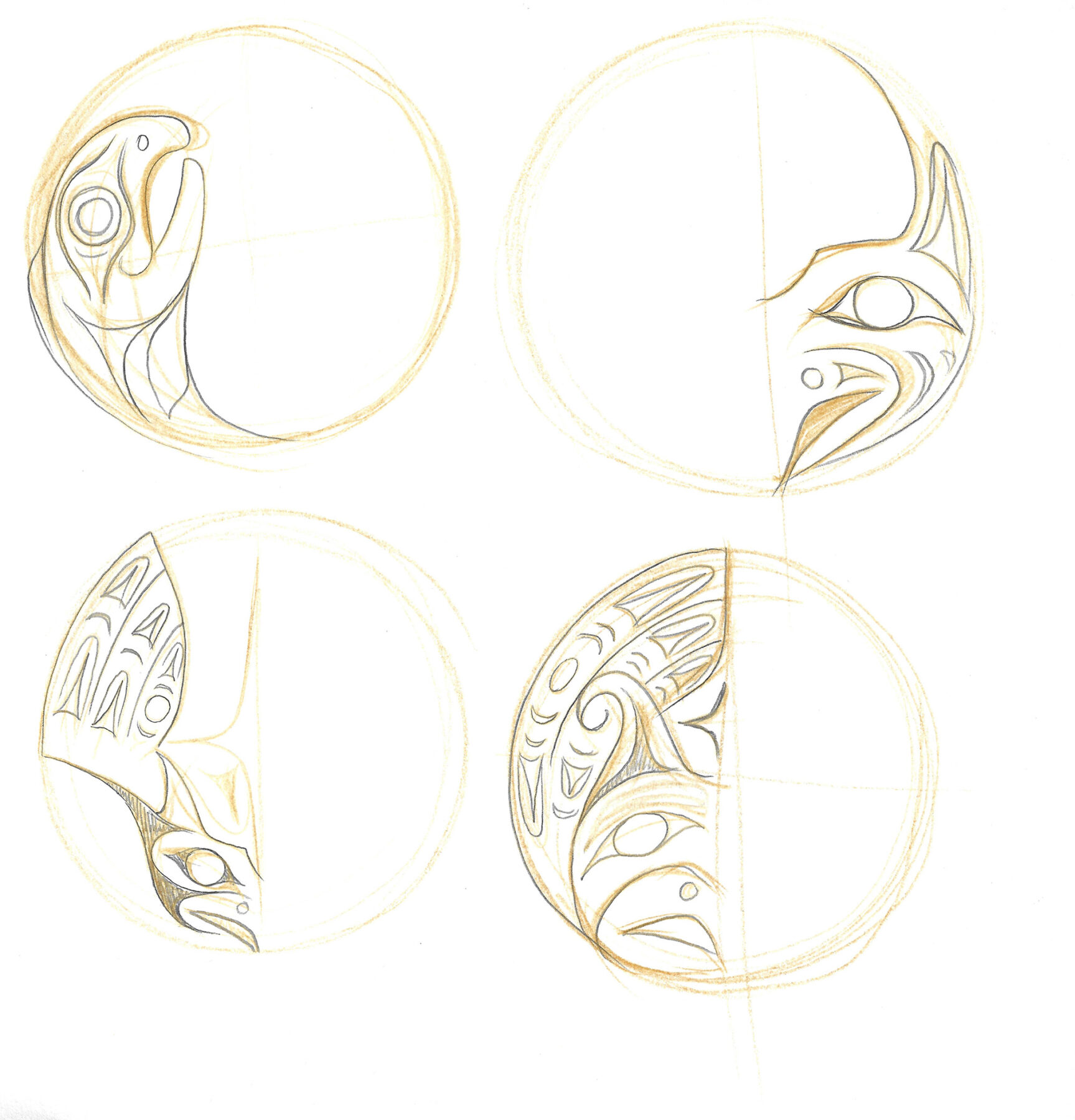

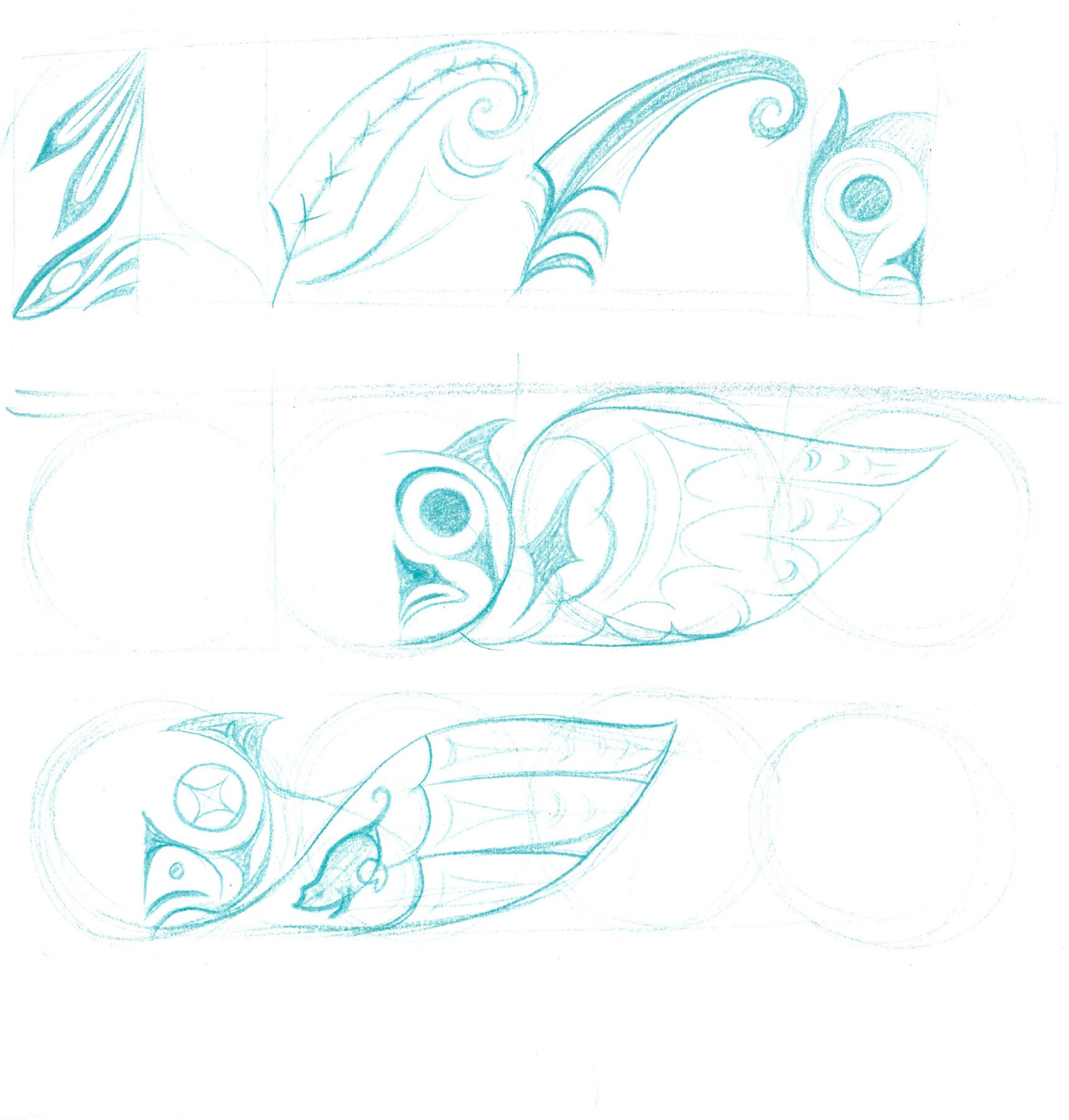

Atheana Picha, from Yellow Sketchbook, 2024, colour pencil on paper, 20.32 × 20.32 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

AP

. . . It’s also like, okay, if you’re dismissing all the people who don’t live on the reserve – and I think of all the people I know who are Coast Salish who are born off reserve – don’t yell at me for my parents’ thing. Not just that, but maybe they were moved off reserve intentionally. It’s just so dismissive of people who didn’t get a choice. It ignores all the displacement that happened between our people.

About learning our culture within the institution . . . I’ve got opinions on that. I think it’s really valuable to connect with people through working at a college, but something we’ve been talking a lot about is: can our design language even be taught in a classroom setting? We’ve obviously had to shift things and adapt to change – one of my elders calls it the “big change” [laughs] – and this is how we modified our teaching to suit a colonial setting. But for some people, it works for them, and for others, it doesn’t.

I’ve also been thinking about the parallels [between educational institutions and] commercial galleries. I didn’t grow up in my community, so I liked looking [at art] in galleries because I got to see Native art outside of a book. But it takes away so much of the context when you look at things in galleries. Often there are things that shouldn’t be put on display, or gallerists and curators who – I don’t want to say they’re just making money off of it, but – who maybe don’t know the context either. I also think about this in the context of institutions: What do we share in an institution? What is something for everybody, versus something for Indigenous people, versus something for coastal people, versus something for Coast Salish people . . . and then within nations and within families . . .

ANM

I got scolded by my teacher once because I was helping him carve, and I went on a big epic rant about how the “stupid museum was stealing all our stuff” and “hell, I should stop carving,” blah, blah, blah . . . I got a pretty good head of steam going. Eventually he said, “Didn’t I teach you to carve? Aren’t you holding a carving knife in your hand right now? You’re mad at museums because we don’t have stuff in our community . . . so make some stuff and stop complaining!” He just had very little patience for my bellyaching about the whole thing. [Laughs]

I grew up with almost nothing cultural around me, in terms of objects. Everything had been either taken from our community or given away, as we did trade and give stuff away as well. So there was nothing in my life growing up, and I felt the loss. But now here was this teacher saying that a lot of that responsibility fell on me, as a maker, to put things back into our community. That really was healing. We’d been victimized so much that it was empowering to take control of my own healing, to take control of my own practice as a carver, in order to leave our community in slightly better condition than we’d found it. To make things a little bit better for the next generation. We used to get to sit with our elders, you know, once a month, when I worked in education, and they really had very little patience for my bellyaching about stuff. They just kept telling me to do more, to work harder, to work smarter. Or to let it go, you know, because we can’t fix everything in one generation. To have some faith in people like Atheana who’ll pick up and carry on and go further than we did. That longer perspective made things a little easier on me.

EDO

You’ve each touched lightly on this idea of time, thinking about the different contexts in which you find yourselves making. How do you think about time as a context for your work?

AP

[Curator] Vanessa Kwan recently came over to my studio, and I was showing them all my baskets and all my books and all these gifts that people had given to me over the years, the things that I’m really excited by. One of the things that came up was some of the prints I have. I have these Art Thompson prints around because I’m really interested in the emergence of Northwest Coast printmaking in the late ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, the era when people really started doing it and it was still a new medium. For a long time, people were only doing a few different [art forms] because that’s all we were really allowed to do. It was fresh out of the potlatch ban, and people were still like, “Okay, maybe I won’t yell at these Natives in the street. Maybe . . . ” So there were all these [new mediums] and we were like, how do we ease into it? I got super interested in the introduction of screenprinting on the Northwest Coast, not just in commercial settings, but in community settings, because of how strongly it caters to our art form. Especially Coast Salish and Nuu-chah-nulth stuff.

I was really interested in the book Robert Davidson: Haida Printmaker1 And what is the other one – Northwest Coast Indian Graphics.2 And then there’s Susan Point: Works on Paper.3 Those are the books I bring when I go into elementary schools or high schools and talk about Native art designing. Because when you look at sculptural work like carving, there are all these aspects to it that are really hard to paint. I like how the Haida Printmaker book shows not just pieces that were made for commercial sale, but also pieces that were like, “Yeah, I’m having a kid! Here’s a card that’s an invitation to the potlatch for the new baby!” And then there are ones that are like, “We’re moving house! Here’s a print of our house that we’re moving into!” with an invitation for a welcoming or a naming.

I still sort of worship Art Thompson, but that’s something that I’m working through. People don’t seem to talk about his influence on Coast Salish art. Something that I really appreciate about Art Thompson is that he’s pretty clear on who his teachers were and the struggles he’s overcome in his life. Some of the commercial gallerists tend to glamorize different aspects of artists’ lives. I mean, I guess everybody does. But we’re human, we have lots of facets to us as beings. To me, it’s really dismissive when people only want to talk about one part of my life . . . like, I’ve got a lot going on!

It was something I really liked about this book, Nuu- chah-nulth Voices, Histories, Objects and Journeys.4 There are four interviews in that book. My favourite are the three: Joe David’s interview with Karen Duffek, an interview with Art Thompson, and one by Tim Paul. I really liked Joe David and Art Thompson’s [interviews] because they’re really blunt. If you see interviews of them on YouTube or whatever, they’re pretty straight up, and in these interviews, they’re pretty straight up too. [Laughs]

Something that I really appreciate about Art Thompson’s work is that he wasn’t limiting himself to certain designs: he also brought things in his life that he was inspired by into his design language. There’s this design – you see it in lots of Nuu-chah-nulth work – it’s a keyhole, some call it. And so apparently – this was relayed to me by my friend who went on canoe journeys and who was talking to John Goodwin or Nytom, who used to work with Art Thompson – apparently in his work, the keyhole design was actually inspired by the railings he saw in the chapel at residential school. And I thought that was so interesting, because there it is: you can bring in shapes that you’re inspired by, no matter what part of your life it’s from.

And so, connecting it to time. All this connects to time! I used to get really bitter, like, “Oh my God, why did Art Thompson have to die? If he were alive for like ten more years we would have been best friends!” I’ve been thinking a lot about that. When these guys were doing these prints – and ladies too, because, well, I guess Susan [Point] was in her 30s – I think, okay, Art Thompson was still learning these designs when he was my age. And then he was also printing and pulling [the screens] himself. And here I am in my basement, pulling prints in the middle of the night, by myself, thinking about what these guys were thinking about when they were my age, while they were printing. And I think about how I’m still learning this medium as well. It would be really cool if I could jump into that book over there, and we could all be printing together. What would we teach each other? And what would we talk about? What would we be laughing about?

EDO

You’ve invited me to think of time as something very physical, which makes me think about time as a material itself. You’ve said, “Sometimes I can’t obey it, but I kind of have to.” I feel like that’s the nature of making, too: when you’re working with materials and they tell you what’s up. It’s a working with and against at times.

AP

It’s funny you put it that way, because I was working on my adze skills – I’m working on a small paddle right now – and I was using an adze on the other side and the grain was just not working, like, at all. And I was thinking about stuff Splash had told me over the years, things like, “You can’t skateboard up stairs,” or “listen to the grain.” How you can only work with the wood, you can’t make the wood work for you. If anything, you’ve got to let the tool do the work, because you can’t force the wood to do anything.

Atheana Picha, from Yellow Sketchbook, 2024, colour pencil on paper, 20.32 × 20.32 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

AMN

If you look at a tree, you see all the years within the tree. So it’s sort of an encapsulated time. And as you dig through the layers, you can see the wood changing – the character of the wood changing. It all coexists in this one form, every year of its life. Some of the old trees we work on are 1000 years old, 1200 years old. So it’s a real living connection to those times.

I remember my grandfather would use this English phrase: “The universe was created, and then, after a while, we went fishing.” [Laughs] It’s really random, but he encapsulated time in that one sentence. How in some ways, time was sort of irrelevant. Think about the first person you ever loved, or the most beautiful moment of your life: it doesn’t really go away or take on any less importance with the passage of time. I think our view, our Salish view, is like that as well. There are some things that are no less important now. Lessons we learned, some thousands of years ago, are as relevant today, or maybe even more relevant, as they’ve ever been.

I recently came across a photograph of a rock carving. And it depicted a tall ship – like, a European ship. I love that this ancient form of artwork – or sharing, or communicating – reflected their contemporary world. So often we’re seen as backwards when we want to engage in our culture, as if it’s a primitive thing that because of the passage of time it should have less relevance. But our culture is also a worldview that’s equally useful in navigating the world around us today. I love that we’re learning a design language, an artistic expression, that reflects equally well our ancient history and our contemporary world.

AP

I like to use baskets to talk about time because it takes so much just to harvest the materials, let alone actually work with them. For example, this basket [holds up a woven basket] took a whole lifetime, or even more than that, to make. Even just to harvest the materials. For cedar bark, you have to wait until the right time of year – meaning you have to have a really strong connection to the environment, to understand what’s going on with the trees – and then you have to harvest the bark, process it to take the outer bark off – they say “just leave it for a year,” and I say “okay!” – thin [the bark] to make sure it’s the right thickness . . . and then you can actually start your basket! That’s not even including the black work. So, the cherry bark, if you leave it in mud that has a lot of iron in it for a year, there are different deposits – once again, connection to the environment – and it turns black. Shain Jackson actually taught me that in Sechelt basketry, the white part is actually corn husk. So anyways, then you’re introducing trade items. All these connections and materials take a lifetime. The materials: two years minimum. And that’s not including the lifetime of skill-building on material harvesting alone . . . you would probably have started as a young person, harvesting for your parents or grandparents. Then comes the actual weaving part – this [basket] was made by a very skilled weaver – and that took a lifetime and a half. You probably came from a family of skilled weavers if you’re doing stuff like this . . . But then, I just buy it at auction for whatever amount of money . . . ? It’s such a bizarre thing to me.

I think about all the other stuff that’s in museums, just thousands of years of knowledge just hanging out, waiting to be visited with and spent time with, all so we can go and draw it and move on. I like going to museum collections and visiting with these things; when I put them down, it’s like I’m saying, “Okay, good night, go back to bed.” You can be really serious with these belongings, and there are definitely some you should be serious with, but I think about Indigenous joy in time as well. Because there’s no way we weren’t joking around way back in the day, too. It’s a big staple of Indigenous living: just finding joy in things and laughing with people.

ANM

I have to repeat something Suzi [Webster] told me – she tells me this all the time. She says, “Our mothers are born with all their eggs, which means that your grandmother actually carried you as well.” She says this to be like, you know, we’re literally connected to our grandmothers, which I think is pretty cool.

AP

My whole practice is kind of dedicated to my grandma, because even though I never got to meet her, I’m talking to her through my artwork. I could talk to her bones all I want, but I also want to honour her impact on my life, for making sure that she was very careful when she carried my mother, because she was also carrying me and my brother. It’s very interesting thinking about creative portals, but also, like Ronnie Dean Harris said, “Our culture is passed through blood and through breath.” I’m like, “Oh my god, here we go again!” because it’s the mothers who carry the breath, and the blood, and this is enriched with everything else. The grandmothers do such a strong job of making sure that everybody is looked after. I’m really close with my grandmother on my dad’s side. My life would look very different without her. So, yeah. I’m just grateful for grandmas today. Thank you!

ANM

Unfortunately, my grandmother was quite a violent person. She kept alive the worst of the residential school in my family. My grandmother was tough and she survived a lot, just not unscathed. I loved her dearly. My family had so much beaten into them in those schools that we’ve been sort of slowly freeing ourselves from the pain of those places. But my grandfather, I spent a lot of time with him, and he was the person I wanted to become, if you will.

I was talking to Atheana about this the other day – since in a lot of our stories, there are not just the teachings, but also the context around them. I was saying how with my family, they told me their stories, but there were also the old stories. Some of them are considered supernatural, and then some of them are not quite fables, but educational stories, illustrative stories. We’ve always had this struggle between what we’ve always done and what’s necessary now, between the traditional and the contemporary. That same struggle seems to go back in our stories quite a long way.

One of the big stories from the village I come from is about a boy who is raised by wolves. He gets lost from our community as a little toddler and is raised by wolves . . . By the way, [the story is] not spoken of as an allegory or anything like that – it’s just history for us. And so, when eventually as a young man he comes to live with us again, he brings all the teachings of the wolf people to us. He is this giant of a man: disciplined and smart and powerful and kind and playful . . . all the things that wolves are. But my grandfather said that amongst the wolves, he was like the runt to the litter. He couldn’t run very fast, and his ears were too small, and he had little teeth . . . you know, that same sense of “I’m not good enough.” And then being of two worlds and wondering where he fit in. I can’t see how this story is not relevant for us today. In a weird way, it’s a very bicultural story. He comes from two different families. And he never chooses between them. He just loves them both. But he has to get to know the Squamish family because he wasn’t raised among us. He has to come back and figure out our culture again as well.

Every time I think of this story and the way my grandfather told it to me, I think of how relevant it is to the experiences and feelings we have today as Indigenous people. The struggle to find our way home, without falling into that binary of having to choose. When you read a little about two-eyed seeing, you’ll see that it’s an attempt to also explain that that sort of either/or thinking doesn’t really suit anyone.

When I started working in schools, I would often ask my elders, “Do we have a traditional role that I’m fulfilling, by working in schools, working with other people’s children?” And they said that I was kind of like a professional uncle: I’m supposed to watch out for them when their parents aren’t around. In my community, if a kid is acting up, people don’t go tell their parents – they tell the aunties and uncles. It’s like, you don’t want to learn to drive from your mom or dad, you want to learn to drive from your aunt or uncle, right? So they were saying that’s kind of what I was, a bit of an uncle. That’s the role I’ve been trying to fulfill.

It’s very different from taking someone on as an apprentice. I’ve shared with Atheana, but we’ve never formalized any kind of apprentice-teacher relationship because then it would get a bit more strict – I would expect her to carry on my family’s teachings in a certain way, and that’s never what I’ve asked her to do. But she’s on a bit of a journey now, and she has many people she’s learned from, and many people she refers to as teachers. I’m one of the people who has taught her, but [Atheana] doesn’t want to be just a Squamish artist – she wants to be a Coast Salish artist, she wants to expand on the whole idea. Which I think is actually more traditional, more historically accurate, in a way: to not just live in a little reserve, but to live in the world of Coast Salish communities.

AP

Thank you, Splash. And yeah, regarding mentors and teachers, I’m pretty clear on who I’ll say is a teacher versus a mentor.

Another thing I’ve been thinking about regarding having teachers from different communities or nations is how during a potlatch there are people invited from so many different places. In the onesI’ve been to, like Musqueam, there are always people from the Island there, and usually Capilano has a whole section, and obviously Musqueam, Penelakut . . . Anyways, there are all these people, and then there are people that are outside of Indigenous communities as well. Sometimes there are museum people, or non-Natives we know. Usually it’s invite-only, but they extend the invitation. And so there are these things about inviting people in, the value of a witness who’s not from your community. Splash, you talk about this quite often, how everybody has a role. Even if you don’t belong to the community, you have a role.

Shaun Peterson also talks about commissioning artwork from different people, from different communities, as a form of relationship-building. I was recently at the American Museum of Natural History in New York and they brought out something that was labeled “Salish.” I looked at it and was like, I don’t know if it’s Salish. I was thinking, Well, it does say it was collected in Musqueam, so maybe it was a commission by a Northern carver that was at Musqueam at the time? There was also a blanket that was Salish-woven: a mountain goat and dog hair blanket. It was really beautiful. But it had formline painted all over it! And it said it was Nuxalk formline! I thought that was really cool because the Nuxalk are Salish isolate, since the language is related. And I have a grandmother five generations back, following lines of grandmothers, who is Nuxalk, and her name is Mary Starr – I’m so proud that I can say that. There are all these things that connect us.

EDO

People may encounter your work in very different contexts, Atheana: within an exhibition focused on a single medium, like drawing or weaving, for example, or in a public mural. What are the relationships that underpin your work?

AP

You know, it’s funny, I did this talk at the Libby Leshold Gallery and someone said, “People understand you have a large breadth of work.” And I got kind of pouty about it for some reason. I was like, “Yeah, but people can’t take me seriously as a carver!” And so when I got the opportunity to be in this show in New York,5 I was like, “Oh my God, it has to be a carving. It has to be a three-foot round red cedar panel, because maybe people will start taking me seriously as a carver . . . ” blah, blah, blah, blah. Because people will say, “Oh, you do a lot of different types of stuff,” but they keep me in a sort of bubble. My close friends understand that I’m playing in different mediums all the time and they all inform each other.

Something I really like about working with Splash is that he’s never just focusing on one thing. If he’s engraving, he’s also working on tons of different types of jewelry at the same time. Or someone will be like, “Hey, can you make a blanket pin?” and all of a sudden, he’s working with wood, working with silver, working with fasteners, and also [making something] as a functional unit while representing something cultural. There are all these things that are connecting. The same goes for a lot of “material practices,” even though I hate that term so much – I’m like, “It’s all material!”

Something that Splash mentioned that I’ve also been thinking a lot about – because every once in a while I’ll slip up – is how we’re often told that we’re “not enough.” Like, I don’t speak my language. I live out on a blueberry farm in Richmond. And I don’t have any woolly dogs, I have chickens . . . So how am I Native? It’s not because I’m wearing these things . . . What makes you Native?

And I was thinking about how Splash carries himself, and how he carries these teachings with him all the time. It’s like he’s never alone. He’s always got mentors and teachers and elders behind him, and not just behind them, but pushing him forward in the world. [Laughing] They’re also standing with him. That is, I think, a big thing in Salish culture…in Nuu-chah-nulth culture, for instance, they’re all standing or sitting in a line, in birth order, but in Salish culture, we’re all lined up around each other. We’re working together as a unit. It doesn’t have to be a family unit, but it could be family in the broader sense, like “you’re a sister to me.” Anyways, once again, I could ramble about this all day. But I really value all the teachings that I’ve learned from Splash over the years and I’m really grateful that I get to work with him again.

- Hilary Stewart, Robert Davidson: Haida Printmaker (Douglas & McIntyre, 1979). ↩︎

- Edward S. Hall Jr., Margaret B. Blackman, Vincent Rickard, Northwest Coast Indian Graphics An Introduction to Silk Screen Prints (University of Washington Press, 1981). ↩︎

- Dale Croes, Susan Point, Gary Wyatt, Susan Point: Works on Paper (Figure 1 Publishing, 2014). 4

Alan L. Hoover, ed., Nuu-chah-nulth Voices, Histories, Objects and Journeys (Royal British Columbia Museum, 2000). ↩︎ - Alan L. Hoover, ed., Nuu-chah-nulth Voices, Histories, Objects and Journeys (Royal British Columbia Museum, 2000). ↩︎

- The exhibition Grounded by Our Roots, curated by Aliya Boubard and featuring work by Hawilkwalał Rebecca Baker-Grenier, Alison Bremner Naxhshagheit, SGidGang. Xaal Shoshannah Greene, Nash’mene’ta’naht Atheana Picha, and Eliot White-Hill Kwulasultun, opened at the American Museum of Natural History in New York on April 3, 2024 and runs until Spring 2025. ↩︎