Garry Thomas Morse

I believe in the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality, which are seemingly so contradictory, into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality, if one may so speak. It is in the quest of this surreality that I am going, certain not to find it but too unmindful of my death not to calculate to some slight degree the joys of its possession.

–André Breton

Many thanks are owed to Elizabeth Bachinsky, who invited me to discuss the process of writing Discovery Passages (the first book of poetry about my mother’s people, the Kwakwaka’wakw) in the Notes on Writing issue of EVENT Magazine, and also to Lorraine Weir, who by brilliantly sussing out so many of my sources in Canadian Literature gave the book the most comprehensive review I may ever receive on my work. I am content to let the subject speak for itself, aside from a few points that seem pertinent to recent literary kneejerks and inklings.

Lately, I have been thinking a lot about Surrealism. I am told a few more of my thoughts will be present in the upcoming issue of Open Letter on Canadian Surrealism, and I feel it would be timely, however fractalishly, to delve a bit deeper into the artistic motivations behind Surrealism and also to explore some of the artistic interstices in which a West Coast Surrealism has subsisted, and how that has and continues to relate to ongoing practice by poets, artists, and dramaturges.

Last year, upon entering the Vancouver Art Gallery to see The Colour of my Dreams exhibition concerning the Surrealist revolution in art, I was startled to encounter a Kwakwaka’wakw figure (Yakan’takw – Speaking-through post) tucked behind the liminal. I was also pleased to discover that in this wonderful curation by Dawn Ades, a respectful sensibility had been achieved, which I find rare in the positioning of such artefacts in various museums and galleries. There is a grandeur and solemnity to this welcoming creature of wood, and one feels its open mouth is inventing whatever is to follow. Without a doubt, it was a nice change from the Museum of Anthropology for Yakan’takw. I was also very much awed by the Kwakwaka’wakw heron juxtaposed with Edith Rimmington’s The Oneiroscopist.

At the time of this exhibition, I realized that the American collector, George Heye, who happened to purchase my familial frog from Indian Agent William Halliday and is parodied in Discovery Passages, also acquired a headdress that ended up in André Breton’s study.

(Yakwine – Peace dance headdress. Photo: Trevor Mills, Vancouver Art Gallery)

In her piece in the Vancouver Art Gallery catalogue for the same exhibition, “A Kwakwaka’wakw Headdress in André Breton’s Collection”, Marie Mauzé indicates that “[t]he headdress followed a separate route from the approximately 450 artifacts confiscated from the Kwakwaka’wakw at the time” although as she also points out:

[i]t did share the temporary home of other pieces in the Surrealists’ collections, the Museum of the American Indian. It was bought in 1926 by the famous New York collector and founder of the MAI, George Heye (1874-1957), from the wife of Donald Angermann, the policeman who had arrested the Native chiefs in 1921. With the complicity of local authorities Angermann rewarded himself by keeping several of the seized pieces.

Incidentally or not, with Joanne Arnott and Russell Wallace, I recently had the honour of taking part in a celebration of Pauline Johnson’s work that was organized by Victoria Poet Laureate Janet Rogers, who gave inspiring readings (and also a presentation on Johnson based upon her research conducted at MAI) at the Native Education College in Vancouver. This was followed by some debate about the significance of Pauline Johnson’s act of choosing to sell a wampum belt to collector Heye, with the provision that she could buy it back at a future time. This is rather a tenuous thread I am following, but it is another echo of the politics and ethics surrounding creation, collection, and commerce (and even coercion?) in relation to the arts.

The Vancouver Art Gallery catalogue for this Surrealist exhibition also features “Scavengers of Paradise”, a comprehensive essay by Colin Browne that examines the Surrealist encounter with what was called l’art sauvage or primitive art:

the surrealist relationship with the ceremonial objects of North America was complex, fluid and often naively idealistic. Many surrealist artists became collectors of primitive art but were unaware of the provenance or function of the objects they acquired or that certain masks may not be shown in public. Collectors would have been startled to discover that some of the Alaskan Yup’ik masks they acquired in the 1930s and 1940s were not much more than twenty or thirty years old, and it’s possible that those who made and/or danced them were still alive, although their names were unknown. The fiction of anonymity allowed for the suggestion that the objects were timeless and belonged to no one. The argument that an object might belong in its place of origin hardly occurred to collectors in 1930; today it cannot be ignored. Between the time that masks, rattles and totems began to appear on the market in Paris early in the twentieth century, and the day in 2005 when Breton’s daughter returned a headdress acquired by her father to Alert Bay, the surrealist eye had altered considerably.

A lot of background perhaps, but the exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery made me acutely aware of a connection between at least two of my literary interests and creations, and therefore revealed a not so tenuous bridge across my subconscious interior (where much of my work gets done). I was intensely aware of something I had been trying to express about not just the cultural and artistic practices of the Kwakwaka’wakw but my own literary ideas and forms of expression and then suddenly I realized that this exhibition might help to provide a dream vocabulary of sorts.

Since writing my collection of oddball stories Death in Vancouver, I have indeed been trying to find a vocabulary for expressing my own artistic approach. I am reminded at times of creations by my celebrated cousin Sonny Assu, whose art often “re-appropriates” commercial iconography, if one may so speak. There is something delightfully subversive in this approach, and this has made me more aware of my own ongoing creative impetus, which involves the ingesting of literary oeuvres and then what I have heard Marie Clements calls the “chewing over of words”, followed by a charming and only marginally painful spitting up. George Bowering poeticizes this process very well in The Gangs of Kosmos (Anansi, 1969):

The Kwakiutl youth aspires

to become hamatsa, the elite,

his patron Baxbakualanuxsiwae,

in a word, he-who-may-eat-human-flesh,

four pieces at a time,

to swallow without chewing,

then disgorge with swallowed sea water.

I also like what Bowering says about The Holy Life of the Intellect. And I do know that lately, on reading tours, I have been drawn into wayward discussions about alchemy, spirituality, the shamanic, and the Orphic. These subjects have been an interest of mine for some time, not just in terms of cultural practice or tradition, but in relation to a long list of poets that includes Guido Cavalcanti, Li Po, Federico Garcia Lorca, Arthur Rimbaud, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Jack Spicer.

In the 40th Anniversary Issue of The Capilano Review, I was relieved to find slight reinforcement from Maxine Gadd, who references one’s “daimon”, a term to be found in Plato’s Ion and a term that I believe Spicer used in relation to himself. Rimbaud found a similar reference to Plato’s description of the poet in an essay by Montaigne, who also refers to the “Daemon of Socrates” in his essay on the subject of Vanity, but it amounts to about the same thing:

The poet, says Plato, seated upon the muses tripod, pours out with fury whatever comes into his mouth, like the pipe of a fountain, without considering and weighing it; and things escape him of various colours, of contrary substance, and with an irregular torrent. Plato himself is throughout poetical; and the old theology, as the learned tell us, is all poetry; and the first philosophy is the original language of the gods. I would have my matter distinguish itself; it sufficiently shows where it changes, where it concludes, where it begins, and where it rejoins, without interlacing it with words of connection introduced for the relief of weak or negligent ears, and without explaining myself. Who is he that had not rather not be read at all than after a drowsy or cursory manner?

Either as spiritual practice or pseudo-science, as in Rimbaud’s “Letters of the Seer”, there is the acknowledgement of the poet acting as medium for something otherly or external, what Robin Blaser has referred to as THE OUTSIDE.

Gadd also makes a statement similar to one I have been frequently expressing concerning the Kwakwaka’wakw, an admittedly dramatic people. However, in this cultural setting, theatre and dreams have historically played a more important role than in other settings. By that, I mean that theatre has a vital significance and that what transpires in the “acting out” of a dream-world is taken with a certain amount of gravity. This is not a static hieratic exhibit in a transparent box behind a security sensor. This is not separate from life. There are in fact, consequences to acting, to dreaming… Or as Gadd indicates:

yes, theatre is real. People–we–are totally formed into symbols at an early age, and theatre is involved with characters that are symbols, really. We are expected to act as symbols: the perfect stenographer, the perfect mother–so what is reality? Reality is a dream.

Ironically, even as Gadd makes a number of interesting statements, she relegates poet bill bissett to an “innocent” from the 60s, or at least limits him to the role of certain attitudes at that time, and also with Romanticism. bill bissett, also as symbol, as 60s Romantic perhaps? I am thinking less of Gadd’s light-hearted remark than I am of an academic tendency to misunderstand and undervalue the amount of collective energy and potentiality in bissett’s work, not to mention its highly relevant multidimensionality. Frankly, the situation has not been entirely dissimilar to the reaction of the first ethnographer to see a Sun Dance, or something to that effect, and remains so to this day.

The Capilano Review – 25th Anniversary Issue

I’m highly “unedumacated” so I likely lack the tools to effectively analyze one of the bill bissett paintings in my office space. However, the painted figure with the open mouth that reoccurs in many of bissett’s paintings (and on book covers) is not so very unlike the aforementioned figure of Yakan’takw that was on display at the Vancouver Art Gallery. I am generalizing, but there is often such a figure in a bissett painting, and there is also often a charged kinetic and a concomitant sense of oral invention. Here is an interesting perspective on a similar painting of bissett’s, from Carl Peters’ (i)-opening textual vishyuns: image and text in the work of bill bissett:

The open mouth may also be read as the third eye–the seat of the soul–which perceives reality [as it is] beyond space and time. It recalls the “opening of the mouth” ceremony in ancient Egyptian funerary practice–the final gesture of the priest that allows the body to breathe the eternal life in “the land to the west.” Each open mouth in any one of bissett’s figure recalls the “golden dawn” of the Kabbalah, which means “to hear” and receive the divine Word: a building up and an immersion within the very ground of being, which is material language. Once again, figure emanates ground, is made of it–is one with it.

This extends to bissett’s performative element at his readings, in spite of his semi-comic persona and poetic approach, which he accompanies with chanting that I presume has an even deeper level of sincerity. This is more like tribal practice, as value and gratitude is given to the speaker, performer or storyteller. Perhaps it is on account of our short attention spans and cynicism nowadays that only through a semi-comic approach can we “get away with it”. However, this is an example of a shamanic approach to poetry, and it underlines the seriousness of the presentation to the point that many other readings seem bereft of such an atmosphere.

Even as I ramble on in tongue-in-cheek fashion, I find it somewhat amusing that, according to Browne,

[i]t was in the presence of a tribal mask in the home of the poet Guillaume Apollinaire that [Breton] first heard what he called, “the interior voice within each human being”

How lovely for him. However, in spite of Breton’s strongly held anti-aesthetic position, also emphasized by Browne, there is a common instinct here in returning to earlier forms of art in order to discover something new. Antonin Artaud, whose ideas I will continually refer to, expresses a similar desire in The Theatre and Its Double:

To make metaphysics out of spoken language is to make language convey what it does not normally convey. That is to use it in a new, exceptional and unusual way, to give it its full physical shock potential, to split it up and distribute it actively in space, to treat inflections in a completely tangible manner and restore their shattering power and really to manifest something; to turn against language and its basely utilitarian, one might almost say alimentary, sources, against its origins as a hunted beast, and finally to consider language in the form of Incantation.

I would venture that such a metaphysical use of verbal charms has more than a little bearing upon bill bissett’s performance of his own works. In textual vishyuns, even in his critique, George Bowering encourages us to look at “the whole gestalt” and “the entire presentation” of bissett’s work. This is something to take into consideration in terms of the oeuvre, the continuous poem in motion, and the continuous line in painting, as Peters emphasizes:

Bowering’s critique of bissett’s work is in no way dismissive. His comment and insight looks to and reinforces the cubist aesthetic, in which the whole, the composition–what the eye finally perceives–is the accumulation of detail, of repeated “parts,” like brush-strokes, for example. And if the eye builds or constructs the image as it perceives it, it can also de-construct it–dissolve it. Hence, bissett’s technique of molecular dissolve in painting applies equally well to his constructions and word-assemblages–the fragment breaks the whole down. The fragment signifies the absence or dissolution of the whole. Without this dissolution there is no assemblage.

If memory serves, I believe that William S. Burroughs once associated bissett’s poetry with the language of dissent. Even if I just dreamed this up, it is not a wholly wrongheaded dream. Yes, Burroughs, whose methodologies involving conditioning, cut-ups, fold-in technique, and the language of advertising have direct relation to the construction of surrealist narratives and works of art, which is a subject Peters also explores concerning work by bissett. In all honesty, there is an elusive element to bissett’s work that I can never quite grasp. If bissett is merely the voice of the “innocent” or of 60’s hippiedom, even in a Blake-ish sense of “innocence” as Gadd may be getting at, then what is the purpose behind all of this obfuscation which is an additional layer to more common attempts by poets to democratize language?

I will not presume to inject a politic into bissett’s work. I would prefer to hypothesize that if there is a politic that is to remain open to interpretation, his linguistic style is a better vehicle for it, one which cannot be so readily appropriated. If there is subversion at work, not only will the work have a better chance of survival in its respective form, but due to its camouflage of sonic consonants, it is likely to remain off the radar of anyone that could negatively repurpose or pose harm to it. And if there is a message, bill bissett has stayed on it for decades.

In addition, Peters’ book has a chapter on poetry and cinema that relates Surrealistic approaches to film making (in particular those of Luis Buñuel) to the work of bill bissett:

This image-movement makes the text a film: it is a book of pure cinema–a book of pure visual images; as are the texts, shaped visually to assert this opposite the collages; these images hold our gaze; collage, bricolage and montage are the new humanist expressive modes. They assault the subject, but a subject is still present. This aspectual nature of his poetic fins an analogue in the opening scene of Un Chien Andalou, where the viewer’s eye is cut with a razor–cuts away the subject–this I–from the object of its original gaze. It also forces that eye, our gaze, back; it forces the reader to look for the other within. This modernist scene is the site of rupture and suture of identity simultaneously. We have been assembled; our eyes have been opened.

Going further, Artaud stresses the importance of theatre over film as a mode of expression, citing poetry itself as the medium:

Through poetry, theatre contrasts pictures of the unformulated with the crude visualisation of what exists. Besides, from an action viewpoint, one cannot compare a cinema image, however poetic it may be, since it is restricted by the film, with a theatre image which obeys all life’s requirements.

A while back, I had the opportunity to see Electric Company’s Tear the Curtain! by Jonathon Young and Kevin Kerr. Under Kim Collier’s visionary direction, simultaneously making use of the Stanley Theatre in Vancouver as a multidimensional space for the audience, the performers, and their ongoing celluloid interaction via film while incorporating Artaud’s concepts of theatre into its meta-narrative, the play culminates in a sort of breakthrough in its presentation that for the audience calls the nature of theatre, film, and reality into question.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3dxv11KD9yA]

Electric Company was also behind No Exit (notably featuring the beguiling actor and dramaturge Lucia Frangione), a fascinating adaptation based upon Jean-Paul Sartre’s 1944 existential classic Huis Clos. In addition to Tear the Curtain! this is an intriguing foray into experimental drama that well transcends the expectations associated with what Artaud called “after-dinner theatre”.

Along with Marie Clements’ innovative drama The Edward Curtis Project, which greatly inspired my poem in Discovery Passages “The Indian Picture Opera”, I have a particular fondness for Larry Tremblay’s Abraham Lincoln Goes to the Theatre, although I am also a fan of many of his works. His play begins with the motivations that led “actor” John Wilkes Booth to seek fame through assassination, and throughout the work reveals how this same instinct is equally affecting other celebrity-obsessed performers who ultimately fall victim to this prospect of their own narcissistic lure. But once again, I defer to Artaud, who indeed speaks of theatre as almost as a kind of contagious ailment or complaint:

There is no point in trying to give exact reasons for this infectious madness. It would be as much use trying to find reasons why the nervous system after a certain time is in tune with the vibrations with the subtlest music and is eventually somehow lastingly modified by it. Above all we must agree stage acting is a delirium like the plague, and is communicable.

Tremblay’s play is complex, particularly as it starts to fold inward recursively. One critic thought it was the kind of thing one either raves about or walks out of, in spite of Tremblay’s ability (not unlike Kim Collier, Jonathon Young and Kevin Kerr) to challenge our critical facility as complacent observers while asking us to also listen for “the interior voice within each human being”. Both works blur the line between the observer and the activity he or she is observing.

Here, I am reminded of an antique quip by the poet Martial:

Since you knew the lascivious nature of the rites of sportive Flora, as well as the dissoluteness of the games, and the license of the populace, why, stern Cato, did you enter the theatre? Did you come in only that you might go out again?

This discussion of critical complacency is relevant in a time when a marketing triumph may be perfectly equated with a personal triumph, when the participant achieves a height of illusory autonomy by achieving maximum contagion, by “going viral”. In Society of the Spectacle, Guy Debord outlines how the power structures once associated with religion and mysticism have given way to an active consumerism in terms of the identification and worship with celebrity figures and culture:

The celebrity, the spectacular representation of a living human being, embodies this banality by embodying the image of a possible role. Being a star means specializing in the seemingly lived; the star is the object of identification with the shallow seeming life that has to compensate for the fragmented productive specializations which are actually lived. Celebrities exist to act out various styles of living and viewing society unfettered, free to express themselves globally. They embody the inaccessible result of social labor by dramatizing its by-products magically projected above it as its goal: power and vacations, decision and consumption, which are the beginning and end of an undiscussed process. In one case state power personalizes itself as a pseudo-star; in another a star of consumption gets elected as a pseudo-power over the lived. But just as the activities of the star are not really global, they are not really varied.

Perhaps our reactive instinct is the same as in other ancient cultural contexts, save that it is co-opted by interests that are less our own. Possibly for commercial or political purposes. The point is always that our emotions are directed toward a singular goal, and that one brand wins out over another. In the Kwakwaka’wakw Hamat’sa rite, which is dramatized in Bowering’s poem “Hamat’sa” and also in Death in Vancouver, the young person who would be chief remains aloof of the village for days in rather uncomfortable conditions, and then in performance, upon return, actively “loses his wits” and must be tamed by the community. Or perhaps I am attempting in vain to find logic in our (unsettling?) obsession with celebrity cycles, in terms of meteoric rises via “reality” viewership, various meltdowns, breakdowns, malfunctions, and even MTV Awards dancing scandals.

So one may hypothesize that in the desired form of art or poetry or theatre, if not the entire cure for what ails us, this would have an ameliorative effect along the lines of the catharsis long associated with Ancient Greek drama. Artaud offers this as an alternative way of reclaiming and redirecting our respective energies:

Either we will be able to revert through theatre by present-day means to the higher idea of poetry underlying the Myths told by the great tragedians of ancient times, with theatre able once more to sustain a religious concept, that is to say without any meditation or useless contemplation, without diffuse dreams, to become conscious and also be in command of certain predominant powers, certain ideas governing everything; and since ideas, when they are effective, generate their own energy, rediscover within us that energy which in the last analysis creates order and increases the value of life, or else we might as well abdicate now without protest, and acknowledge we are fit only for chaos, amine, bloodshed, war and epidemics.

While speaking of theatre and/or surrealism, I would be remiss not to mention the work of J. Michael Yates, self-described on his hardcover memoir as “poet, playwright, and prison guard”, and author of such surrealistic curiosities as Man in the Glass Octopus, Fazes in Elsewhere, and The Passage of Sono Nis, named after the press that Yates founded, Sono Nis Press. There are touches of Beckett and elements of absurdist theatre in his plays, and in terms of his fiction, he strikes me as the closest thing to Jorge Luis Borges on the West Coast.

For several years, I have been an ardent enthusiast of the work of French poet Robert Desnos. In the “halcyon days” of the Surrealist movement, when these fine fellows in Paris were sincerely trying to hypnotically induce one another to hang themselves for a lark, Desnos was rather a darling of André Breton’s, due to his peculiar talent for entering into trances and performing miraculous feats of speech and automatic writing on the fly, replete with bizarre wordplay that also concealed a deeper resonance.

In his First Manifesto of Surrealism, Breton has nothing but encouragement for the talent and abilities of Desnos:

Ask Robert Desnos, he who, more than any of us, has perhaps got closest to the Surrealist truth, he who, in his still unpublished works and in the course of numerous experiments he has been a party to, has fully justified the hope I placed in Surrealism and leads me to believe that a great deal more will still come of it. Desnos speaks Surrealist at will. His extraordinary agility in orally following his thought is worth as much to us as any number of splendid speeches which are lost. Desnos having better things to do than record them. He reads himself like an open book, and does nothing to retain the pages, which fly away in the windy wake of his life.

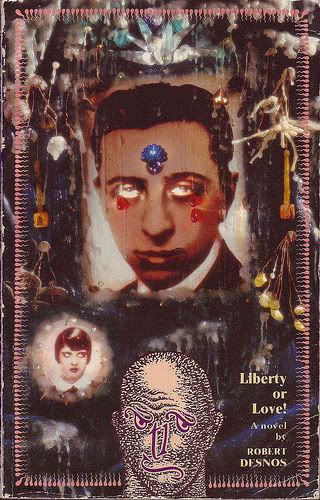

(Liberty or Love! – Robert Desnos – Atlas Press)

Notwithstanding, in the introduction to Desnos’ masterpiece, the pages he did retain for his Surrealist novella Liberty or Love!, translator Terry Hale indicates that the book:

has a greater thematic unity than might be expected of a purely automatic text and the action, or so it has been hinted, would in some sense seem to have been directed (the best evidence for this being the numerous self-referential passages).

Still, the style of the novella bears comparison with the films of Luis Buñuel, in which the logic of linear narrative is challenged and broken down into fragments. I would reckon that Liberty or Love! also heeds Breton’s admonition regarding the potential enslavement of the imagination (by ourselves):

The mere word “freedom” is the only one that still excites me. I deem it capable of indefinitely sustaining the old human fanaticism. It doubtless satisfies my only legitimate aspiration. Among all the many misfortunes to which we are heir, it is only fair to admit that we are allowed the greatest degree of freedom of thought. It is up to us not to misuse it. To reduce the imagination to a state of slavery–even though it would mean the elimination of what is commonly called happiness–is to betray all sense of absolute justice within oneself.

For another interpretation of “freedom”, we once again turn to our friend Artaud:

Now one may say all true freedom is dark, infallibly identified with sexual freedom, also dark, without knowing exactly why. For the Platonic Eros, the genetic meaning of a free life, disappeared long ago beneath the turbid surface of the Libido which we associate with everything sullied, despicable and ignominious in the fact of living, the headlong rush with our customary, impure vitality, with constantly renewed strength, in the direction of life.

In Liberty or Love!, Desnos most often decides upon erotic themes as a means of reaching “the interior voice within each human being”, and as the title indicates, this is a form of revolution that occurs within the individual that is not necessarily congruent with the amount of unrest at the barricades. In one of his essays, Desnos indeed posits that any philosophy whose morality does not contain an EROTIC is incomplete.

This reverts to an earlier strain of philosophical rebellion against religious authority in France. Even the Marquis de Sade, who even at his most distasteful, has made an interesting presentation (and precedent in French literature) by the mere act of juxtaposing exhaustive passages of philosophy with those of pornography to the point that they both are revealed to be capable of being equally banal. When writing of Sade, Simone de Beauvoir perceives his work from a surrealistic angle:

Actually there is only one way of finding satisfaction in the phantoms created by debauchery, and that is to accede to their very unreality. In choosing eroticism, Sade chose the make-believe. It was only in the imaginary that Sade could live with any certitude and without risk of disappointment. He repeated the idea throughout his work. ‘The pleasure of the senses is always regulated in accordance with the imagination.’

These are variations on this theme that are to be found in French literature, almost as a nod to the tradition of Sade, in the work of Isidore Ducasse (Comte de Lautrémont), Jean Genet, Georges Bataille, Marcel Proust, and of course, Robert Desnos.

And just as Søren Kierkegaard gave life to a fictional aesthetic seducer in his early tract on the philosophical erotic after the mysterious breaking off of his own engagement and just as Gérard de Nerval, a surrealist pioneer, fashioned his chimaeras around his idealized love for actress Jenny Colon, Desnos gathered together his own work on love and the erotic that was intensely connected with his passion for the singer Yvonne George. I’m not sure whether it was the opium use or her entourage of obsessed fans that put a damper on the mood but it didn’t really work out. Based on the nature of Liberty or Love!, at turns romantic, cynical, and absurdly hilarious, I would surmise that he was seeking a form of love that would not in Breton’s words “reduce the imagination to a state of slavery.” This does not mean that Desnos practices avoidance of the sheer materiality of commodity fetishism. Au contraire:

Suddenly, I noticed the presence of a white border around her calves. This border grew rapidly, slipped to the ground, and when I reached the spot where it had fallen I picked up a pair of exquisite cambric cami-knickers. They fitted perfectly in my hand. I unfolded them and plunged my head into them with delight. They were impregnated with Louise Lame’s most intimate odours. What fabulous whale, of whatever colour, could distil a more fragrant ambergris. Fishermen, lost in the fragments of the ice-floes, who permit yourselves to perish from an emotion strong enough to cause you to fall into the icy waves, once the monster has been hacked to pieces, the blubber and the oil and the whalebones necessary for the manufacture of corsets and umbrellas carefully garnered, you discover the cylinder of precious matter in the yawning belly. Louise Lame’s cami-knickers! What a universe!

(Bébé Cadum)

However, even in his mockery of religious dogma, Desnos makes fantastic use of commercial iconography. The great Manichean battle will involve Christianity in the form of a contraceptive sponge (alluding to the sponge allegedly present at the Crucifixion) and also in the form of the divine Bébé Cadum (a grinning baby associated with a bar of soap), who is pitted against the original embodiment of might and machismo, the hard drinking chain smoking Bibendum Michelin (rough and tumble ancestor of the extremely non-theatening Michelin Man) whose name and credo is derived from a Latin line by the poet Horace that essentially means Now let’s get wasted!

(Bibendum Michelin)

Quite recently, I was delighted to have chance to read at the same event with Steve McCaffery, and to hear him read from “The Cook’s Tale”, which is also in the 40th Anniversary Issue of The Capilano Review. Apparently, fresh from perusing Chaucer, McCaffery somehow manages to lampoon pretty much all of the above:

Ten seconds earlier “ rice cakes butter and bukkake baths” appear in a passage of automatic writing being penned through the subconscious mind of Marcel Latrine, the infamous surrealist from Liège. You can rest assured mon ami that blowing up a book is like blowing up a building. Giovanni Rocco Focaccia is commenting between one of Marcel’s pauses. Giovanni Rocco Focaccia is a superannuated Futurist of small merit. He believes his canvases are the sacred places where Captain Speedy meets the little bombardier and personelles all extant surfaces with parole in liberta. Gimme spontaneous nihilism every time retorts Hugo Ernst the famed lame Dadaist from Darmstadt, although I have to admit those Surreal images can be quite spooky sometimes. Come to think of it so can other things especially poetry without words. I had previously thought poetry could be the ideal alternative to organized religion but not anymore.

And it should come as little surprise that a number of these ideas and linguistic approaches have helped me formulate my series of five novellas known as The Chaos! Quincunx, which are to appear over the next few years, and constitute a continually transformative parody of novel genre. The first installment Minor Episodes / Major Ruckus contains a tributary novella that pays homage to the Surrealist movement and in particular the work of Robert Desnos. There is also a chapter from Minor Episodes about a cheery public execution in the 40th Anniversary Issue of The Capilano Review. Here’s a clip:

Some choose a mild demise, death by sodium laurel sulfate, CH3(CH2)10CH2(OCH2CH2)nOSO3Na, the common ingredient found in toothpaste and shampoo and a number of personal care products. It has wonderful properties of removal, and excels as a garage floor and automotive engine degreaser. In fact, Minor has a patent in motion to produce a damnably whitening cleanser without this agent, mostly because he suffers from inflammatory carbuncles and breakouts the paste and shampoo exacerbate. He was almost certain Jazzy would want his clock cleaned this way, and would nobly decide to be brushed or scrubbed to death by giggling local breakfast television hosts. Although he had once seen a marketing executive subjected to this fate and the cleansing agent went straight for his follicles. He met his maker bawling, and balding on the spot, but clean as a freshly polished whistle.

“Sodium laurel sulfate. A poetic death if there ever was one! And so much more humane.”

I hereby acknowledge Coast Surreal Territory. Long Live the New Flesh!

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hqRTDnNplKA]