This interview was conducted in September 2019, during Michelle Sylliboy’s residency at The Capilano Review. New poems from her book Kiskajeyi–I Am Ready appear in Issue 3.40 (Winter 2020).

Matea Kulić: Michelle, could you talk a little bit about how you began writing poetry?

Michelle Sylliboy: I started writing poetry when I was going through the Transitional Year Programme at the University of Toronto back in 1988. I knew I was artistic, but I never really thought about it that way, perhaps because my teenage years, you know the years when you’re supposed to be moulded into who you’re going to be, were stripped away. So, writing came late. Everything came late. Two years later, I arrived in Vancouver and got a job at a bookstore—it was one of two Native-owned bookstores in Canada at the time—called Chiefs Masks bookstore. I met Indigenous authors from across Canada who came to the bookstore for book launches and readings. I also became part of a poetry group that the bookstore manager’s friends organized. The people in the poetry group were much older than me, seasoned writers, who loved poetry and encouraged each other, including me. The organizer, the late Ethel Gardner, published a chapbook with the poetry we wrote from those early days and I continued to write after that experience.

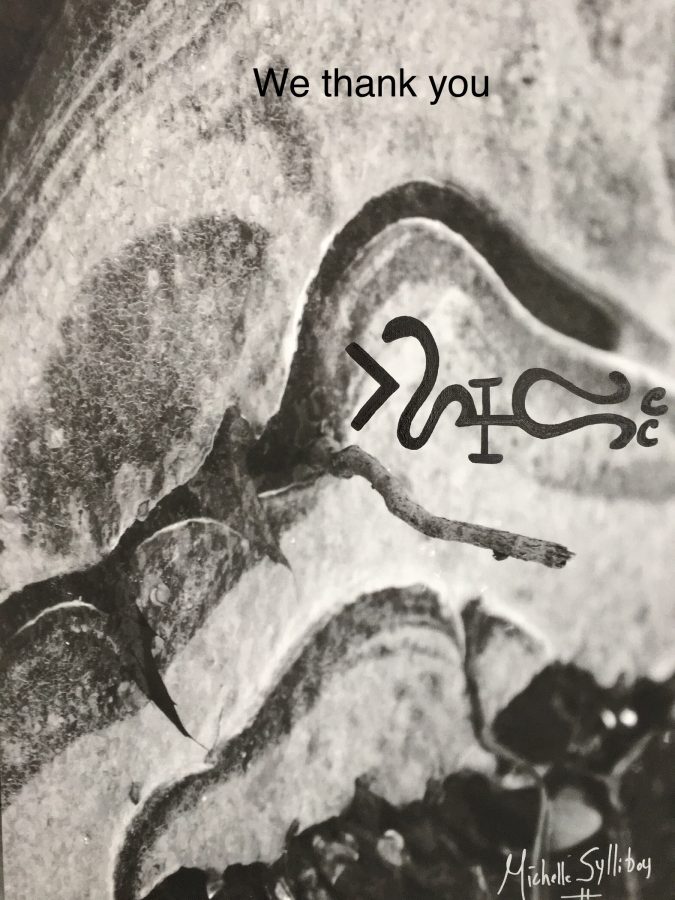

MK: I’ve been reflecting on your interdisciplinary practice, because your work operates on several levels. Included in your book Kiskajeyi—I am Ready is your poetry, photographs, as well as what’s called a “hermeneutic exploration of Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic poetry.” Your performances then bring sound and projection into the mix.

MS: As an interdisciplinary artist, working in different mediums allows me to explore how our creative senses connect to language. Musicians have always been my favourite collaborators because they draw out certain feelings instantly. My photography connects me to the land that the komqwej’wikasikl language originated from as told to me by my elders. I want viewers to connect with the landscape, music, and poetry as a way to invoke different levels of existence and ways of perceiving. A hundred viewers might witness the same performance, but they will all walk away with different perspectives and feelings. That’s a good way to describe my language: everyone brings their own perspective.

MK: During the workshop you presented as part of your TCR residency, you mentioned a lack of awareness about the Mi’kmaq writing system. There’s an emphasis on the oral culture of Indigenous peoples—and you don’t hear much discussion or acknowledgement of Indigenous written language systems.

MS: Well, yes, the historical narrative has been ripped away from Indigenous people all over the world. Historically speaking, whoever is the dominant political power—they run the narrative. It’s taken a long time to reclaim our own historical narrative and place in this country. Indigenous scholars and writers such as Lee Maracle, Ruth Cuthand, Connie Fife, Chrystos, Beth Brant, and many more have contributed to reclaiming our voices. Mi’kmaq scholar Marie Battiste has made significant scholarly contributions to protecting Indigenous language and knowledge.

MK: Can you talk about the history and your contribution to protecting Mi’kmaq language and knowledge in particular?

MS: According to the great knowledge keeper and Mi’kmaq elder, Murdena Marshall, prior to 1942 a lot of people could read the hieroglyphs. After 1942, in Cape Breton, and particularly in Nova Scotia, my elders went through what they called a “centralization period.” The federal government decided, in 1942, to put all the Mi’kmaq people in Nova Scotia in two reserves—Shubenacadie and Eskasoni. They promised the families: “If you move to Eskasoni or Shubenacadie, we’ll give you a house, we’ll give you land to farm…” It was all a ruse to get them out of the community. When the people arrived to the reserves, nothing was there. No houses were built. No resources were available to build their houses. No farmland, nothing. When they came back to We’koqmaq, their houses were burnt down. In my own community of We’koqmaq, only seven families stayed behind, and it was because of those seven families that my community survived. My grandfather was the only one of his seven siblings that did not move to Eskasoni; he stayed behind to help rebuild the community.

After 1942, the written language started to die out due to the separation of families and elders. Very few elders could teach workshops to preserve the language in their communities, and the prayer books that the priests had developed for the purposes of evangelization had become the historical record of the language. But it wasn’t the church that preserved the language. It was my ancestors. Each generation did their part to retain the Mi’kmaq memory of the language.

So, now that it had become my turn, I thought, “How can I modernize it and do something a little differently than what my elders did?” Even before the book was published, I was doing workshops in Native and non-Native communities. Last year, I took part in the Lumière Festival in Sydney, Cape Breton. It was busy—like a Disneyland attraction—but it was an incredible experience. People drew their own hieroglyphic messages onto a computer monitor, and over the course of the evening, the symbols were projected onto this massive wall. Hundreds of people lined up, and I’d say maybe a handful of people knew we had a writing system. Even in schools that I went to in the Maritimes, the youth were unaware. “We didn’t know you had a writing system,” was something I heard a lot.

I always knew that my first book of poetry would be in my language, but I thought it would just be phonetic. It never dawned on me to use the script of the ancestral Mi’kmaq language. But my experiences in workshops and in the education system confirmed for me that I needed to restore the historical narrative and also reclaim the language.

MK: Many of our readers are poets and translators themselves, and I think they’d be curious to hear more about the process involved in the translation of the komqwejwi’kasikl hieroglyphs. I notice sometimes a greater number of symbols than you might expect are required to describe certain things, the phrase “each day,” for example, in “Komqwejwi’kasikl 5.”

MS: There are no easy answers because the symbols are not all there and because the language is very descriptive. The Mi’kmaq language is verb-oriented and one word can have multiple descriptors. We describe a situation, and that’s the complexity of the language. The hieroglyphic symbols in Kiskajeyi allowed me to describe in three different formats: in Mi’kmaq hieroglyphics, in English, and then, phonetically. When I read the work in public, however, the reading itself becomes a fourth element, and the language changes again. It’s a difficult thing to wrap your head around, but the way I learned the Mi’kmaq language is as a language that describes the moment. That’s why you’ll have many different interpretations of one word used in different contexts and stories.

MK: How did your community respond to the book and your use of the komqwejwi’kasikl writing system within it? Are you seeing the hieroglyphs come into everyday use as you had hoped?

MS: Well it’s the first hieroglyphic poetry book, so people are like, “What?” [laughs]. But, seriously, people are so proud that we have a written language, and they’re hungry to learn it.

A lot of work still needs to be done. A dictionary needs to be completed. A keyboard as well. But all that requires a lot of time and energy and funding and funding [laughs]. But it’s inspiring people, including a new generation of younger people with amazing skills. If it’s doing that, then the purpose has been fulfilled.

MK: This work is so important Michelle—thank you for sharing some of the intentions and history behind it. Do you have any last words for us?

MS: The late Lillian B. Marshall was a well-known Mi’kmaq historian and language expert. When she found out about the reclamation work I was doing she was very proud. She said, “Michelle, you make sure you tell them, we always had the writing system.” Those words had a profound effect on me. We always had this writing system. She passed away shortly after, but I will always mention what she said because there are people who believe the dominant historical narrative left behind by the priests. I’m not going to argue because it’s their perspective, it’s how they see the world. But I choose to believe my elder Miss Lilly—because her timeline is infinite.