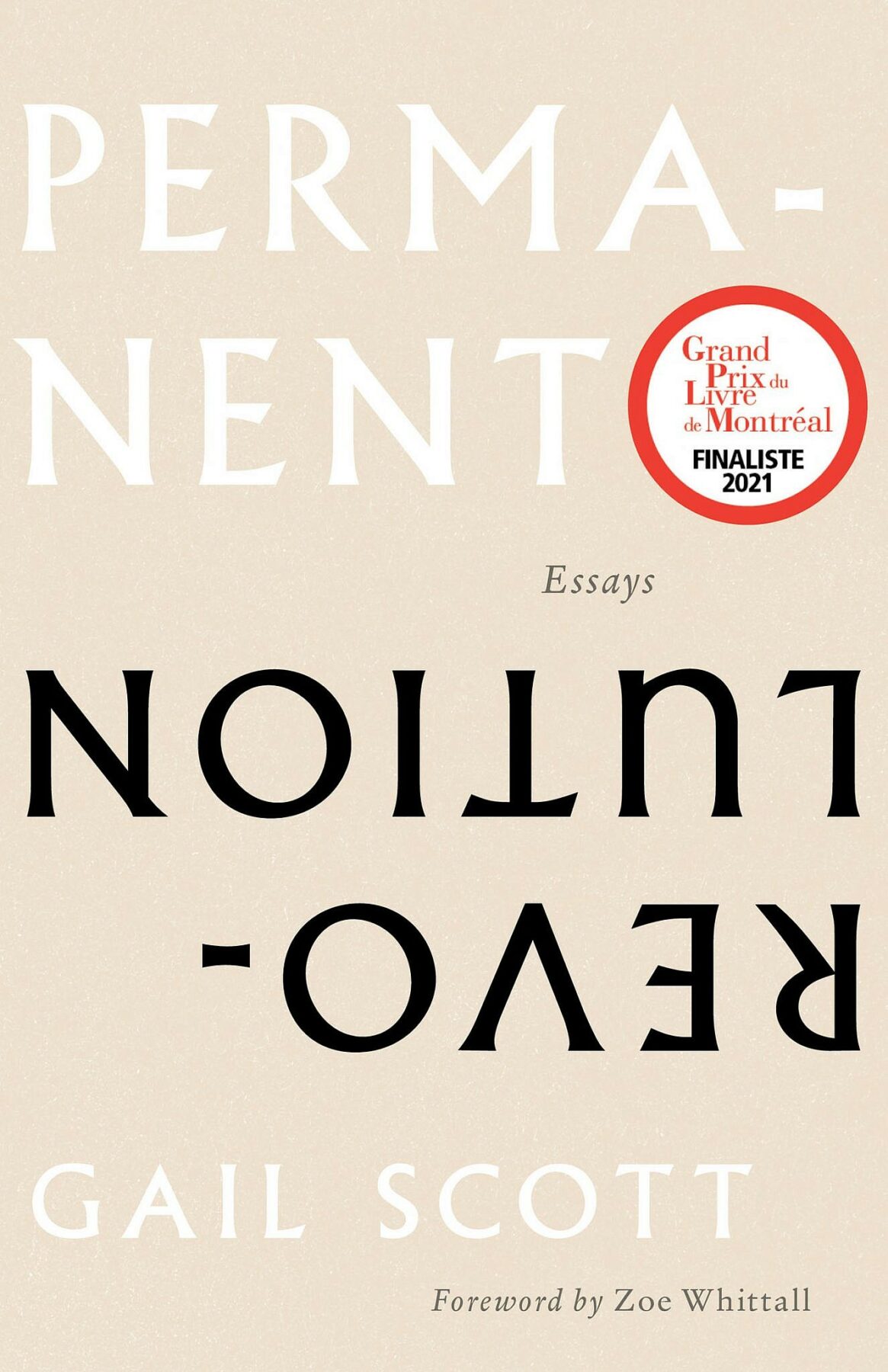

The twelve essays that make up Montréal writer Gail Scott’s Permanent Revolution: Essays include a mélange of newer and older pieces, and focus Scott’s attentions to her social, political, and structural engagements. Through prose and the particulars of the sentence—especially attentive to elements between and simultaneously through French and English thinking—she revisits and reworks older essays, unafraid of the adaptability of her thinking, as she moves and considers writing-as-thinking and re-thinking. In “The Porous Text, Or the Ecology of the Small Subject,” she describes wandering the streets of Paris “in search of a lost avant-garde, increasingly settling for conversation with dead Gertrude Stein + Walter Benjamin. [Her] question to them: how does one learn to stand, as a writer, as forward-looking thinker, in relation to one’s own language + time?” Her thoughts are ongoing, ever open to seeing what other possibilities exist. Or further, to introduce the selected and “somewhat revised essays” from her 1989 collection Spaces Like Stairs (Women’s Press, 1989), she writes:

Hopefully, something about these struggles for more democratic approaches to living in a community of sentences is modestly useful as we continually attempt to widen our grasp of what it means to be a fully present integral person in the broader body politic.

I’ve grown to appreciate Scott’s ability to refuse a fixed point, whether of language or of personhood, allowing for her sentences and her arguments a fluidity and adaptability; how conversations shift and change as new voices emerge, and different ideas are presented. Moving through Scott’s reworked pieces, I’m suddenly aware of my own limitations, having previously inwardly chastised poets who would routinely rework and republish poems of theirs that had already appeared in collections (Irving Layton, for example, did this regularly). Through Scott, writing becomes less a moment of captured thought than something ongoing; conversations shift, and our thinking, including our writing, requires adaptation in response. Throughout this collection, as in all her published work-to-date, Scott’s prose blends both the physical and the philosophical. Her work is deeply attuned to both body and gender, and the ways through which language opens, allows, and articulates all the inherent possibilities and impossibilities surrounding the simple yet complicated politics of the female body moving through space. As Sina Queyras offers in their recent Rooms: Women, Writing, Woolf (Coach House, 2022) on and around Virginia Woolf: “Alice Walker in In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens ask[s] what owning a room might mean to writers who did not own their bodies. And what of those who didn’t have a roof, let alone a room?”

If Scott is willing to revisit her published works of fiction, much of which is informed and shaped by the same explorations and ongoing concerns, why not her essays as well? The shifting sand, one might say, is entirely the point, overtop a foundation of openness to clarify, expand or modify her own thinking. Even as her writing moves forward, the texts she has already produced are living and breathing, able to learn, and open to adaptation. To introduce the second section of her collection, a small selection of essays reworked from Spaces Like Stairs, Scott writes that her essays “resonate with a decade of remarkable flowering of feminism in Québec, a decade when the ethical function of the text was underscored in a writing practice greatly concerned with deciphering the effects of social constructs in language, especially for women. The decoding naturally left gaps in awareness. Going back to the essays, I felt a little naked. The essay, perhaps even more than fiction, shows up this youthful person radiant with hope + intractable enthusiasm.”