Late last year, a group show under the modest title of A Practice in Gestures opened at the Richmond Art Gallery (September 15 to November 15, 2021). Curated by Nan Capogna, the show brought together the installations of six artists living and working in BC: Farheen HaQ, Bev Koski, Mitra Mahmoodi, Bettina Matzkuhn, Barbara Zeigler, and Deborah Koenker—the latter two artists have been published several times in The Capilano Review. The show gathered practices and gestures that signal a long history of women’s work—beading, embroidering, folding, washing, etc. Arising from the domestic quotidian is art that references a global scale, identifying colonial and patriarchal power structures and registering environmental crisis.

Fold, the second of two riveting videos by Farheen HaQ, captures a series of repetitive gestures. Framed inside what would be the mirror of a dresser, the video features the artist in the steady, unrushed, rhythmic act of gathering from below an endless quantity of crisp, white cloth—one arm gathers, the other arm holds. The white dresser mirror/video screen is faced by an empty white chair. What does the implied viewer make of this scene? What is the body enacting? As she gathers the cloth into her bare arms, it overflows and spills into voluptuous folds evoking the sumptuous, draped cloth that challenged and obsessed Renaissance painters. Is she the artist’s model? The image is both lovely and perplexing. There’s nurturing in the gesture but there’s also a troubling inscrutability. Is this an image of servitude? One thinks of the contemporary sense of “fold” meaning capitulation. Is it an image of sensory indulgence? Alternatively, there’s a clear reference to maternal cradling of a swaddled infant, and in her spread and draped legs to the iconic Madonna and child of western art.

The master artists, the Old Masters, indeed Art History and its traditions and practices, are never far from one’s mind with this show. Deborah Koenker’s Hanging by a Thread: Feminist Re-Vision, the largest installation of the show, presents 132 framed hand-embroidered landscapes. Two-thirds of them are details from 15th to 19th century drawings and engravings by male artists including Botticelli, Rembrandt, Poussin, Lorraine, Dürer, Mantegna, Turner, Van Gogh, Corot, Pissarro, Bonnard, and others—all documented in detail in an accompanying leaflet. Koenker began the embroideries in 2002 using photocopied reproductions of drawings and engravings transferred to squares of dupioni silk and stitched in black and grey thread. Historically, the woman copyist defers to the master or patron, practicing the lesser art of the sampler. The labour of embroidery past and present would require the use of a circular tambour frame. Here in their gallery and installation context, the embroideries are framed as art works, wryly referencing their ambiguous status as both art and craft. This art historical commentary adds a further satisfying riposte: the remaining one-third of the embroidered squares derive from Koenker’s own drawings of local landscapes, largely trees found in Vancouver parks.

Koenker’s “copies” of the celebrated masters are gorgeous. The shift of media from the drawings/engravings to stitches on cloth introduces its own subtleties and originality. As the leaflet of attributions notes, the embroideries are “after” the masters, e.g., “After Baccio Bandini’s engraving after Botticelli’s drawing, Dante and Virgil in the Dark Wood, 1481” or “After engraving by Diderot and d’Alembert after drawing by Titian from Encyclopedie #1”—after the masters who themselves engaged in reinterpretations. The array of 132 framed embroideries—worked on by Koenker during periods of waiting between taking her children to appointments and lessons, and during work meetings—is an astonishing sight.

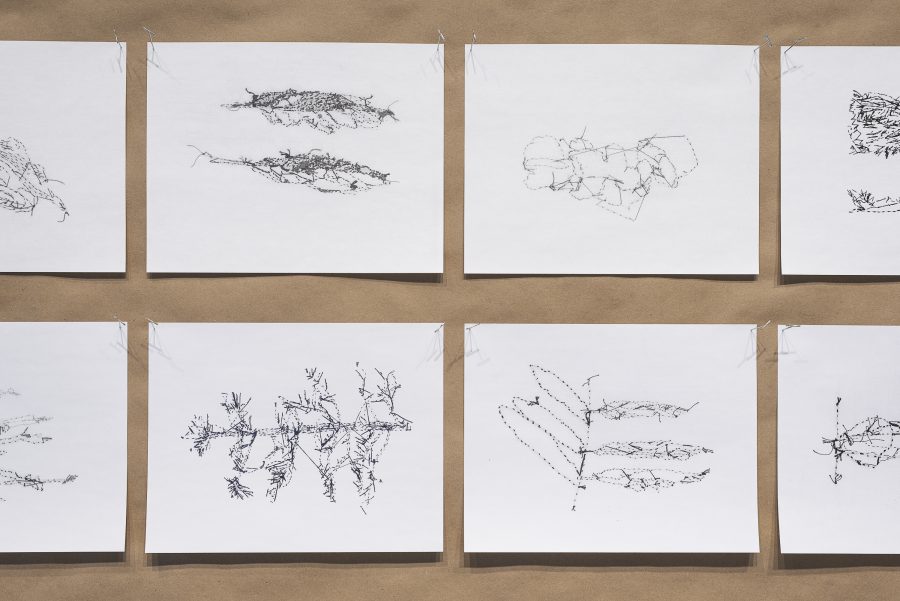

On the wall facing this compressed history of gendered artistic endeavour is the flip side, another kind of history. The artist-embroiderer can’t help but register the networks and patterns of knots and threads on the backs of the embroideries. Photocopied prints of these backs are pinned to the facing wall suggesting maps, so Koenker proposes, of the migratory routes of birds, viruses, and particularly people—refugees in flight from brutal regimes and changing climates. An entirely different experience of waiting is registered here—that of interminable waits at borders, customs checks, and other forms of impeded mobility. Hanging by a Thread is a richly layered work of art.

Bettina Matzkuhn’s work SOS also references refugee experience. Her array of seven empty lifejackets evokes the experience of refugees in contemporary times, particularly the perilous crossings of the Mediterranean and the English Channel. The empty lifejackets are an unsettling reminder of the vulnerability of those who depend on them. Stitched into the interior of the lifejackets, close to the body of the wearer, are richly embroidered nostalgic images of sunny skies, flowering landscapes—an imagined unruptured nature where a life of peace and safety might be anticipated. The installation economically registers the complexities of the rescue proposed by the lifejacket, the life preserver.

The environmental crisis is at the centre of Barbara Zeigler’s two pieces, a video installation, Passage II, and Totally Cracked, which both engage the fragility of nature and human endeavour. In another ritualized practice of gestures, Zeigler has cleaned and saved the shells of eggs eaten by her family over decades. Her three-channel video, Passage II, captures the routine domestic action of delicately cleaning out the shells under streams of running water splashing against hands and eggshells. The video is displayed horizontally suggesting the ongoing, extended, decades-long practice. Accompanying these engrossing images is a floor work of chilling stasis, Totally Cracked—part of a series, Ritual and Change. The cracked and cleaned family-preserved eggshells now rest on a circular, planet-like bed of river rock, doomed fragility against an implacable and inanimate background.

Mitra Mahmoodi’s Aftabeh offers a collection of ceramics created “after” the traditional vessels of her Iranian background. The aftabeh is a pitcher used throughout history for hand-washing and general cleansing—referencing another ritualized practice of gestures. Some of her vessels are functional such as the wheel-thrown pitcher at the top of the stairs that display her pieces—stairs that feature a poem in Farsi by a contemporary Iranian poet—and others are sculptural, abstracted versions that gesture towards traditional shapes. They are weathered and “antiqued,” mimicking the traditional beaten metal in the softer clay. The troubled line between the traditional and the modern is sharpened by quotations from the Quran that are marked on the vessels but partially erased. The selected texts, we are told, promote an ethics of modesty, kindness, and compassion, but the didacticism is deliberately muted by partial erasure of the Farsi texts. Mahmoodi pays tribute to the traditional while using the freer medium of modern sculptural techniques.

Anishinaabe artist Bev Koski’s beaded figurines likewise pay tribute to traditional practices while confronting stereotypes of Indigenous peoples. Pocket-sized, plastic toy figurines representing the “Indians” of “Cowboys and Indians,” sold in tourist outlets across the globe and collected by Koski and friends are meticulously refashioned. The offensive caricatures recover their Indigenous identity through Koski’s application of a beaded exterior. Each of her titles includes the provenance of the small figurines: “Upper Peninsula Michigan #3,” “Toronto #6,” “Disneyland, California #1,” “Banff #2,” “Thunder Bay #1,” “Ottawa #1.” In a series of witty gestures, she has repatriated them from far flung gift shops and returned them to an Indigenous identity. Even in their miniature scale, the work argues, their misrepresentations must be addressed as examples of the countless ways in which Indigenous identities are distorted to match stereotypes and commercial demand. The eyes of each small figurine are left unbeaded and allowed to peep out at the viewer with an effect that complicates Koski’s project. The different states of mind signalled by the eyes—alarm, naivety, passivity, shame—deepen the sense of invasiveness in the creation of the figurines along with an apprehension of the impact of such caricatures on individuals.

With great skill, curator Nan Capogna assembled this collection of resonant practices and gestures, acts of critical attention to the urgent political, social, and environmental justice challenges of the moment.