Beginning in the winter of 2019, Vancouver’s Access Gallery invited Julia Lamare and Julie D. Mills of the mobile Number 3 Gallery to occupy PLOT: a 200-square-foot space adjoining the gallery that is provided to collectives, artist initiatives, nascent or small-scale organizations, and those conducting itinerant projects as a public site for programming, exchange, and experimentation. Number 3 Gallery in turn invited artist and curator Emily Dundas Oke to initiate a loosely bound project titled “you never get to the end of a circle.” Their collaborative residency served as a discursive space to question and resist outcome-oriented organizing, activated by meals, gatherings, and experimental modes of conversation.

The idiom “talking in circles” denotes a way of communicating that is unproductive, indirect, confusing.

𐩒

As far back as memory serves, its body bends. Over itself, folded around its own ribcage, it stretches back through generations of memories. I can’t help but think of memory as an ancestral echo of circles. It comes at me from the future only so I can meet it again. When I stretch my arms out to embrace you, I take note of the circular shape. It holds you, holds me tight. This comfort extends far beyond the horizon of memory’s bend; not every aspect of it is yet familiar.

𐩒

I long for collaborations that use circles. [1]

𐩒

In this visitation, who has the authority to write memory? Can we imagine memory as a circle, as a cacophony of voices?

𐩒

PLOT became a space of uncertainty. As arts workers, artists, and curators we relished the invitation to occupy space without preconceived outcomes, to shed the spectre of productivity seeped in our skin. The invitation spurred both impulsive and deliberate further invitations. Access to space is a rare occurrence in this town for many of us, and being granted the privilege of access meant we aimed to extend it further through a series of tangential collaborations.

𐩒

EDO: What does it mean to be in circle? That very generative space where we are all on the same level. There is no up or down…

𐩒

We propose the notion of speaking in circles.

𐩒

The circle as an organizing method offered a generative and non-hierarchical space for being together. We wanted to undo assumptions of expertise that insist on power and conclusive thoughts. In recreating a kitchen scene, we thought about the potentials of circles, and invited others to create circles of their own through poetry, beading, meals, and conversation. The circle offered us a framework for conversation: permission to question how we communicate and verbalize uncertainties or changing opinions. Our utterances at the kitchen table [2] were and continue to be malleable to the ever-shifting conditions that surround us.

𐩒

in this sharing of our silence there are rounded

corners where bodies circle circles within circles

our bodies fluid

opening to each other we become rounded corners

no sharp turns here [3]

𐩒

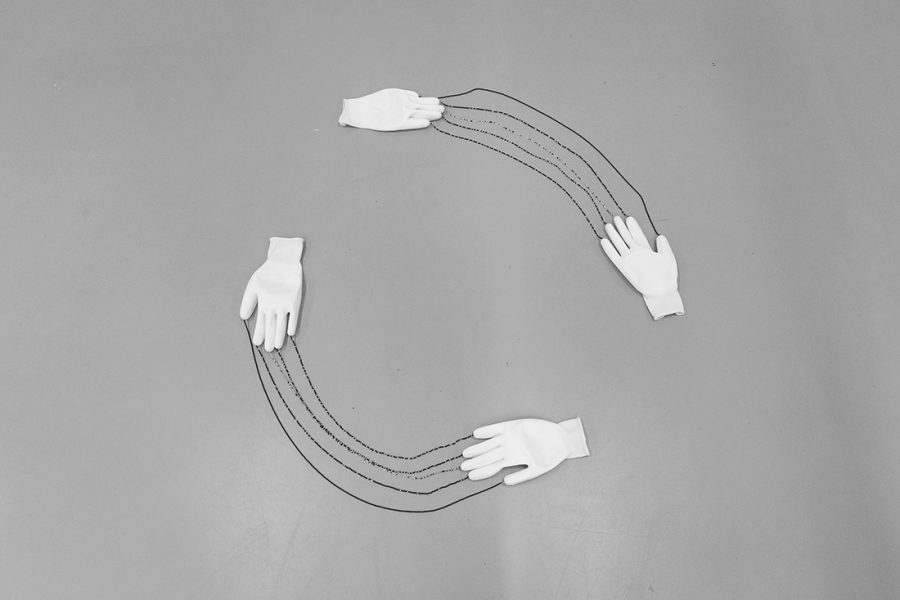

Gatherings often strained under a noted ambiguity: How does the tension of sitting together have the possibility to liberate or suffocate? When power differentials remain present and the terms are already set, it is possible that whoever offers the invitation to sit inhibits new realizations. The circle contained the possibility of a failed gesture. Gloves tethered by beads [4] acted as a visual reminder that things could go awry.

𐩒

Utterances encountered by my aunties generations ago continue to surface and confront bodies today. These discourses repeat, again and again, each time in a slightly different form, but maintaining the same frustrating vibrational tendency. I sense the redundancy of speaking and listening within the framework of state legislative powers embodied across language, land, the familial, and otherwise…

𐩒

We fantasize about a time, or perhaps, a world, where we don’t have to be swallowed up by the same issues as our predecessors. For now, it is our responsibility to continue and propel the conversation they began. We recognize the necessity of a conversation that continues indefinitely. We use repetition as a tool for building and changing narratives. We aim to undo structures, shift the context. We consider gestures or idioms as double entendres that offer new pathways for understanding.

𐩒

Yet here we are presented with the conundrum of the written word. It becomes stuck in its own fixity. It assumes a certain kind of stagnant truth. We think about the histories — artists, thinkers, writers questioning the power of the written word — that have led us here.

𐩒

JK: You know people really hold you to these things. I’ve published these two books, and now I would change them. Now I would have different ideas, now I know more. I would say something differently.

EDO: I haven’t published very much, maybe because of that fear of things becoming cemented in a way. It’s daunting because all of a sudden you’ve “made a claim,” whereas when I am writing, I am just trying to learn, and trying to do that publicly.

JL: Maybe it’s a question of shifting how we think and understand language, writing, or spoken word. There’s an idea of permanence that is tied to anything that becomes a physical form, language or art. If we don’t take everything written as a permanent truth that’s where the shift happens because we’ll never stop writing. Maybe it’s more about the onus on you as a viewer, reader, or listener.

EDO: So much is put onto the truth and knowledge that is built up in writing. You know [historically] it was only men who were allowed to write, only men who were allowed to publish — so in one sense, it’s about thinking differently about the authority and truth of the written word, but it’s also about raising the way that we value other forms of communication and knowledge holding. This is a really political space that we’re making and enacting right now.

JK: And if you did it in a circle, one would hope that that’s confidential, so then it lives on in a different way. That’s where we can learn: where we are allowed to be in process. But this culture we live in does not seem to like process very much, it wants to just get things done, production. I think process is where everything is.

The italicized transcriptions are from two circles held in the PLOT space on January 6 and March 8, 2020 between Jónína Kirton, Matea Kulić, Emily Dundas Oke, Julia Lamare, and Julie D. Mills, where the following texts were brought forward: Disinherited Generations: Our Struggle to Reclaim Treaty Rights for Nations of Women and Their Descendents by Nellie Carlson and Kathleen Steinhauer (University of Alberta Press, 2013); The Invitation by Oriah Mountain Dreamer (Harper San Francisco, 1999); Ceremony by Leslie Marmon Silko (Penguin, 1977); “No. 109” from Bluets by Maggie Nelson (Wave Books, 2009); “A Long Line of Caterpillars” from The Vision Tree: Selected Poems by Phyllis Webb (Talonbooks, 1982); “Lightness vs Weight” from Accounting for an imaginary prairie life by Landon Mackenzie (1997).

[1] Jónína Kirton, “Everything is Waiting,” The Capilano Review, no. 3.39 (Fall 2019): 7-9.

[2] We do not claim the kitchen table as our own, but rather follow the generations of others who had to carve out space for themselves. We wish to highlight what we have learned from the women behind the Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press. See Barbara Smith, “A Press of Our Own Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, Vol 10, No. 3 (1989): 11–13.

[3] Jónína Kirton, “together we walk the labyrinth,” The Capilano Review, no. 3.39 (Fall 2019): 10-11.

[4] The artwork, pictured on page 93, by Emily Dundas Oke is a set of gloves connected by beads, intended to be worn by two people. The gloves mimic a gesture of gratitude, yet are also a device to be used to learn to sit with the other.

you never get to the end of a circle by Emily Dundas Oke and Julia Lamare is featured in Issue 3.40 (Winter 2020). To read the piece in its entirety purchase a print or digital copy here.