In visual art, colour is used strategically. Artists choose one or two shades that they carry through the canvas, extending it through details of fabric, tufts of animal fur, or the shadowy aspects of the sky. This technique ensures that the viewer’s eye remains engaged, moving across the pictorial plane in search of a splash of the familiar within the unexpected. Larissa Lai’s book-length poem Iron Goddess of Mercy employs a similar technique, replacing pigments with language, creating a mural of poesies that traverses continents and historical periods, politics, and popular culture.

The title is a preview of this poetic collaging, combining the reverent yet critical commentary on identity (Iron Goddess is the name of a milk tea) with reference to the duty of the bodhisattva of compassion: Guan Yin, who makes recurring appearances throughout the book in a Where’s-Waldo-like fashion. As in Christian and Buddhist traditions, Lai has her own pantheon of deities, including the late Chinese American journalist and activist Iris Shun-Ru Chang. As Saint Iris, she is a protector and witness to all that has happened and continues to happen, who “looks back at the horror and turns to stone.”

The recurring invocation “Dear” gives Iron Goddess of Mercy the quality of a poetic mural, facilitating the connection of figures and abstract concepts across space and time. Addressing everything from Shrek and Mui Lan (or Mulan in the Anglicized version), Racial Representation and Cheongsam, to “Dear Curb your anger and we’ll throw you crumbs” and “Dear Oolong, if there were no such thing as tea, none of this/ would have Happened,” the text is as much an inventory of the world in microcosmic scale as it is an index of testimonies to struggles both past and ongoing.

Throughout Lai’s book, dear-ness is revealed as a colonial tactic, a gesture of faux-politeness that’s been branded distinctly Canadian. Meanwhile, the genuinely dear and personal remain hidden in plain sight, much like early 16th century Netherlandish paintings of market stalls, where the artist would often hide the religious figures of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph. In these instances, a narrative of personal and familial intimacy unravels, as in fragment 4, where spiritual reverence bleeds into everyday life: “open for business open for booty playing/ footsie with the cooties mark of the schoolyard god’s her own father and she don’t even believe in ‘im.” At the same time, there is a sense of the authorial voice breaking through the veneer, marking its presence the way an artist would when adding a signature in the corner of the canvas.

Lai wields language like a paintbrush, ensuring a connectivity of seemingly disparate elements, sometimes within the confines of no more than a couple of lines. Her wordplay unravels into a spectrum of shades that carry the reader through Iron Goddess of Mercy in waves, “swinging from the hang seng star of my burnt-out metaphor/ burnt-out semaphore signalling darlin’ can’t you hear me, sos.” They also signal to the inseparability of past and present, high- and low-culture, as Lai charts a non-linear path through history that is a testament to the refusal to remain passive.

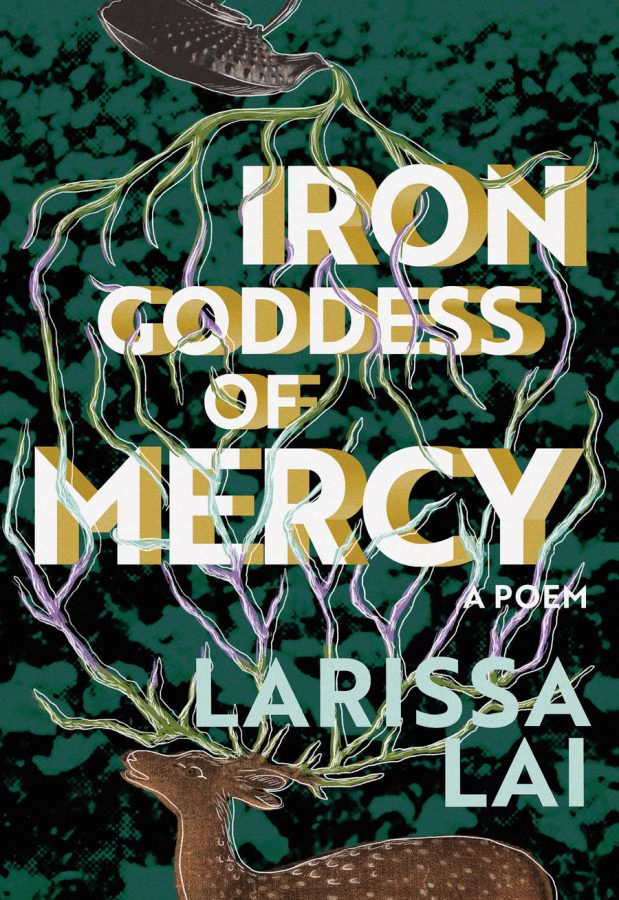

Iron Goddess of Mercy by Larissa Lai was published by Arsenal Pulp Press in 2021.