From Issue 3.23 (Spring 2014): Languages

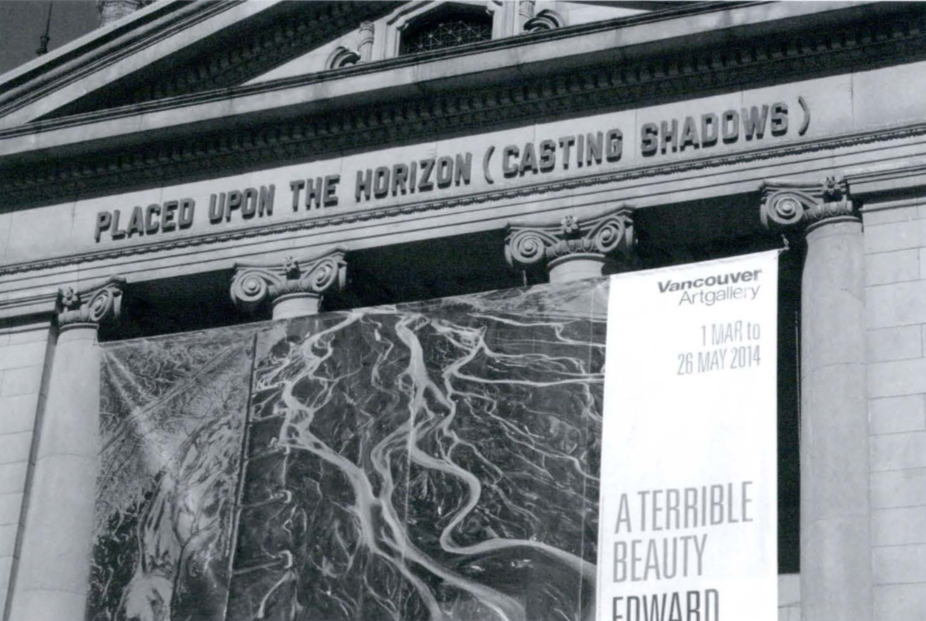

750 Hornby Street (Vancouver Art Gallery)

Seven years after relocating to Vancouver’s former provincial courthouse, the Vancouver Art Gallery commissioned American artist Lawrence Wiener to produce a text for public view. The text is a phrase carved from indigenous yellow cedar and attached proudly to a frieze above the gallery’s closed-off southern portico, its letters “casting shadows” during the day before retreating into darkness at night. Thus, Weiner’s text is not a literal self-referential work “placed upon the horizon” of the VAG’s rooftop, but an advertisement for what lies inside; not a locus of market certainty, but a symbolic site where ambiguity pervades. In short, a civic art gallery that, despite recent efforts to move to a purpose-built “iconic” structure, remains at the centre of the cosmopolitan city.

555 Hamilton Street (Del-Mar Hotel)

Those approaching the 500 block of Hamilton Street will note the presence of a slim three-storey hotel surrounded by BC Hydro’s towering corporate headquarters. While the hotel appears to reflect a utility company’s recognition of that which came before it, we have instead a hotel owner who refused to sell his property at above-market value to a corporation that wanted the entire end of the block, but to continue to provide clean rooms and below-market rent to those in need of a subsidy. This is what artist Kathryn Walter chose to work with after her site visit to the Contemporary Art Gallery (which at the time occupied the lone storefront space beside the hotel’s lobby). The result is a corporate-style text designed so that the oxidization of its 7”-high copper letters would one day match the colour of the rear and sides of a building that stands not only in resistance to Hydro’s monopolization of this block, but for a world where people come before profits.

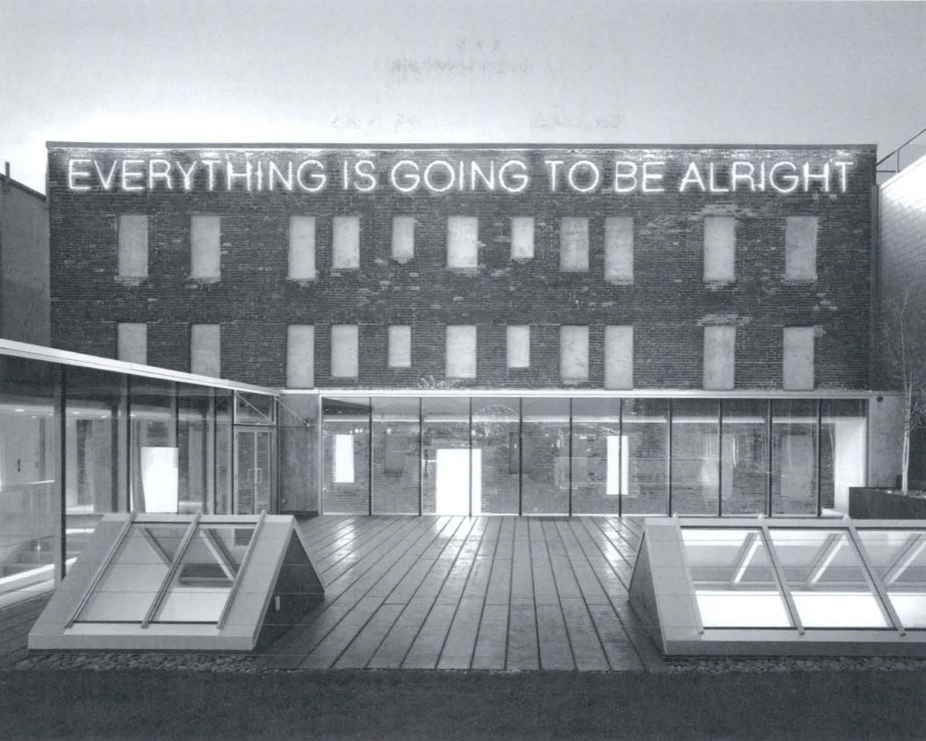

51 East Pender Street (Wing Sang Building)

Photo credit: Martin Tessler. Courtesy Rennie Collection.

This work of neon text, commissioned by real estate magnate Bob Rennie and attached to his Chinatown palais, will be forever wedded to the year it was made. For it was in 2008 that the world experienced what is softly called a “downturn,” an event whose consequences depend on who you talk to: if it is a single-parent mom working as a paralegal in Chicago, it was the year the bank foreclosed on her one-bedroom condo; if it is a man who made his fortune selling condos, it was the year the public had to be convinced not to lose confidence in the market as an arbiter of what is good and right, and that sooner than later you will get your condo back, perhaps with a second bedroom. If the informational content of this British artist’s text is not enough to allay our fears, consider the formality of the declaration: not EVERYTHING’S GONNA BE ALRIGHT, like the pop song says, but EVERYTHING IS GOING TO BE ALRIGHT, as if spoken into a camera by a tele-prompted politician.

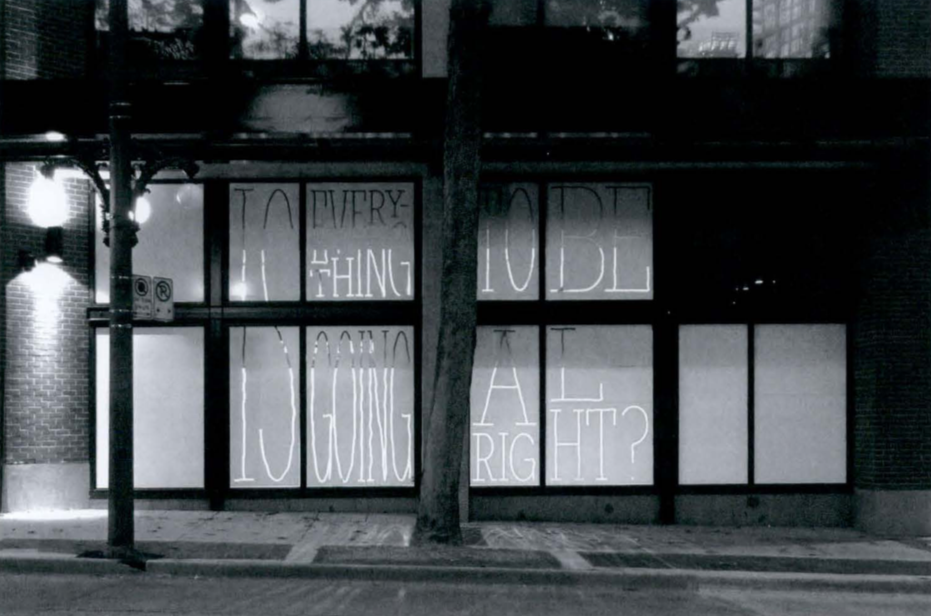

149 West Hastings Street (Audain Gallery/Goldcorp Centre for the Arts)

Photo credit: Sabine Bitter

Although not a permanent work of public art, Kathy Slade’s Is Everything Going to Be Alright? was designed to converse with one, namely, Martin Creed’s Work No. 851, located three blocks away from the windows of the Audain Gallery, where Slade’s text (one of four works by former SFU students commissioned by the gallery) was installed in the wake of the 2010 Winter Olympics. Made of shiny weeded vinyl and applied directly to the glass, Is Everything Going to be Alright? comps on Pablo Ferro’s long, narrow titles for Stanley Kubrick’s Cold War satire Dr. Strangelove (1964) and appears to those aware of Creed’s commission as a retroactive preemption, one that takes the chill off his declaration by transforming a unilateral command into a dialogical—if somewhat more compassionate—response.

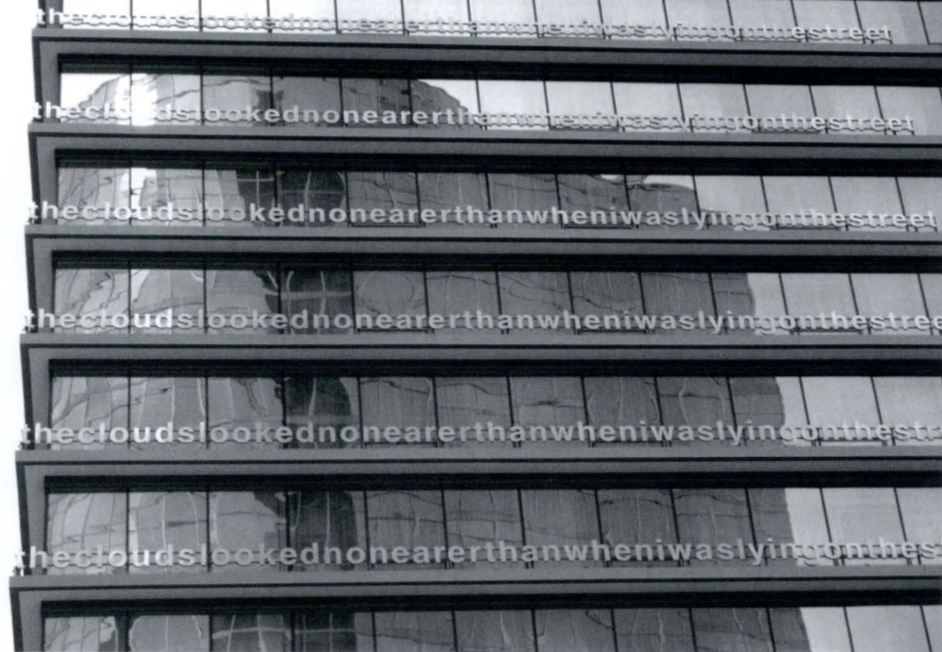

299 Burrard Street (Fairmont Pacific Rim Hotel)

This repeated text—a vertical extension of the floor plates between the fifth and twenty-second storeys of an exclusive downtown hotel—presents itself as a koan but behaves closer to an apology for a building that obscures the clouds that its text has asked us to consider. While true that the height of this building is insignificant compared to the distance between the street and the clouds above, it is particularly insensitive to those who live in a city where “lying on the street” will get you arrested—to say nothing of a hotel whose security guards would accuse you of trespassing if they found you on its roof. Of course this is a literal reading, but to consider this British artist’s cummerbund text independent of the tuxedoed building that supports it is to mistake a ponderous thought for a passive-aggressive taunt.

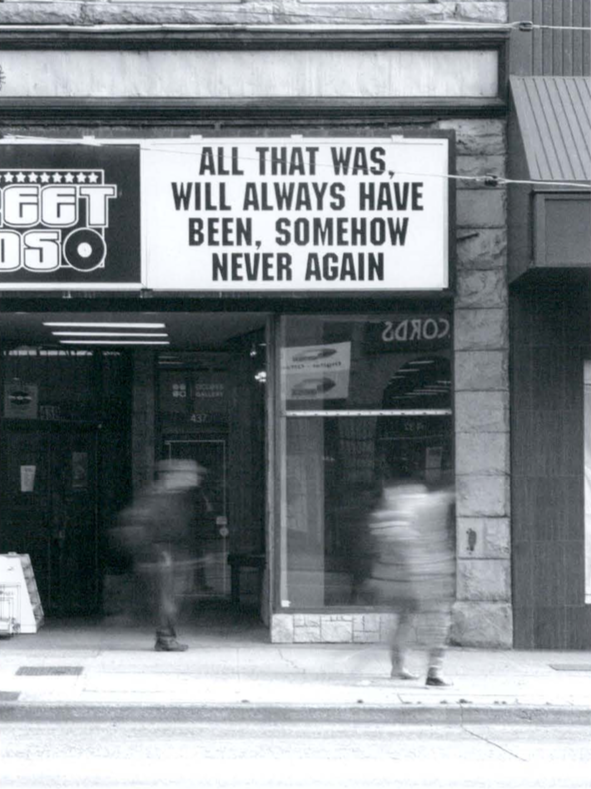

Raymond Boisjoly, All That Was (2010)

437 West Hastings Street (Access Gallery)

Past and future tenses, a passive dependent clause, and a negative conspire to form a text that, in an attempt to ground ourselves in its temporal calculus, slows us. Indeed, it is within this slowness that questions seep in: What is for sale here? Whose land am I on? Why do I move so quickly through the city? Unlike other galleries with texts on their buildings, Boisjoly’s was left to the elements after its commissioning agent, the artist-run Access Gallery, was forced to move due to steepening rents, leaving All That Was to join the ranks of its prescient title.

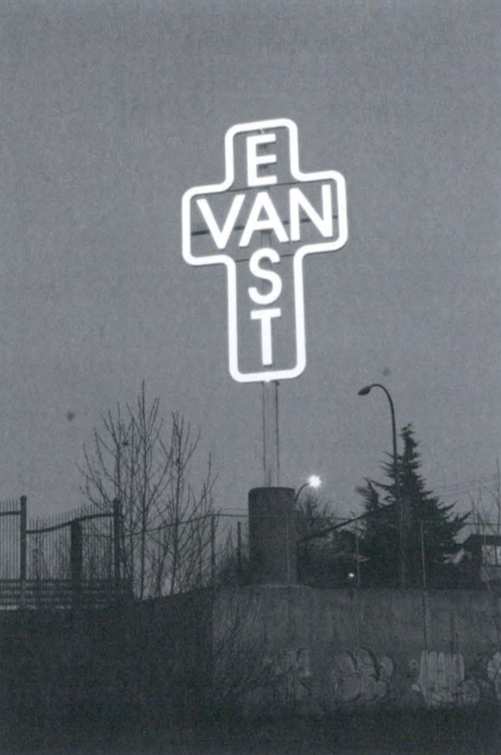

Northwest corner of Clark Drive & Great Northern Way

Photo credit: Ken Lum. Courtesy the City of Vancouver Public Art Program.

At 19.5 metres high, this concrete, steel, and neon cruciform stands at an East Vancouver intersection like Rio de Janeiro’s Christ the Redeemer and is visible to those wealthy enough to afford cliff-top homes in West Van. Although widely admired by those who live within the city’s historic working class and immigrant east side, initial criticisms of this 2010 Winter Olympic commission focused on the artwork’s Christian iconography, accusing it of reviving the WASP monoculture that flourished in Vancouver until the late-1970s. However, for those who grew up with this symbol written in felt pen inside Stanley Park toilet stalls or carved into bus stop benches in Kerrisdale, it is a mark of pride, one that traces the outward movements of those whose otherness is synonymous with their invisibility, something the artist experienced as a teenager every time he stepped from neighbourhoods like Strathcona or streets like Kingsway.

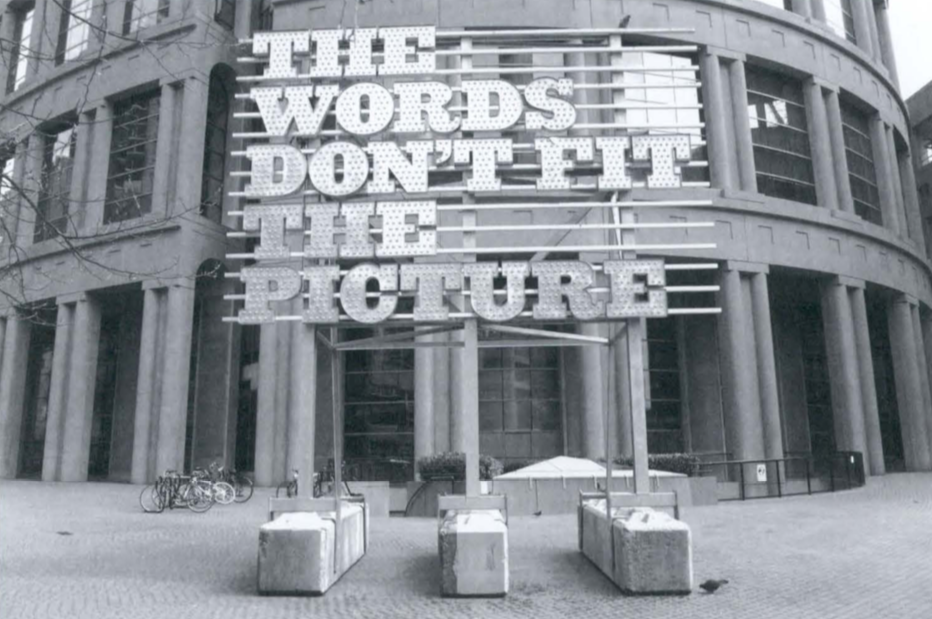

350 West Georgia Street (Vancouver Public Library Main Branch)

The “words” in this Olympic commission are LED lights set inside letter-shaped aluminium dishes that, over five lines, move from a left margin towards the right end of a rectangular galvanized steel support rack. As for the “picture,” its field is the totality of that support, and to suggest that the words inside it “don’t fit” is to equate fitting with completing. Instead, the words merely fit within this support, leaving space, like poems do, or pictures can, like the photo-paintings of Ian Wallace, who combines photographic images and painted monochromatic space(s) that amount to a bigger picture, one that includes not only photographed human subjects but the monochromatic space they have either stepped from or are about to enter into, a potential derive space where a viewer can only imagine where the subject has been (or where that subject is headed next). But at night Terada’s work takes on a different shape, one devoid of the supports that make it less a picture than a text that asks us to imagine one.

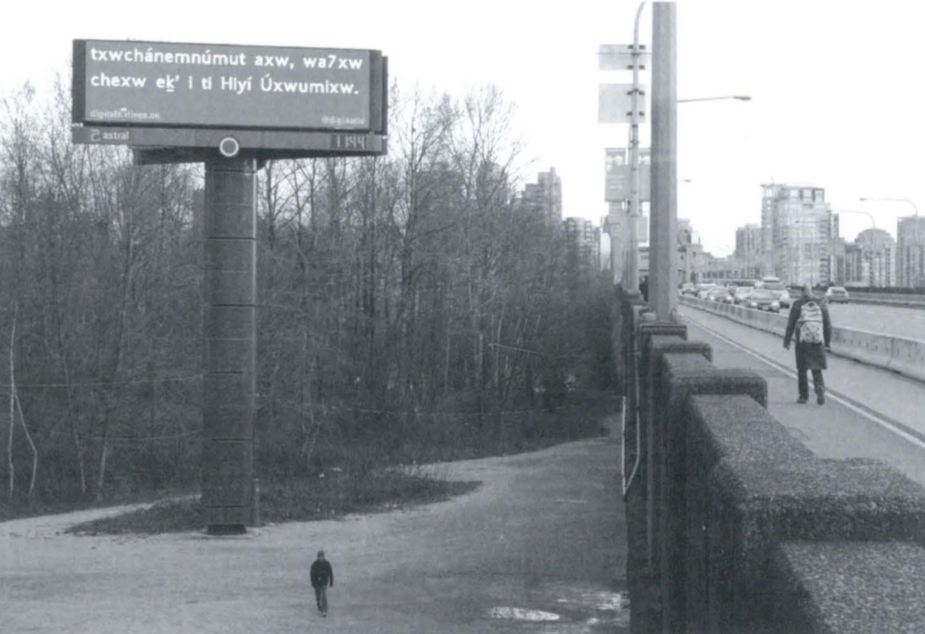

South End of the Burrard Street Bridge

Photo credit: Barbara Cole

This Vancouver 125 commission, whose title is a play on the Skwxwu7mesh territory on which it was staged and a nickname for those who grew up in the digital age, involved thirty First Nations and non-First Nations artists and writers who were invited by the Other Sights artist collective to submit a tweet-sized text (with provision for unsolicited tweets to come) to be screened at ten-second intervals amidst commercial advertisements on a large electronic billboard operated by Astral Media (on behalf of its owner, the Squamish First Nation). These English and First Nations language texts, which ran the gamut from aboriginal-settler conflicts to formal experiments in concretism, were on display to pedestrians, cyclists, and motorists throughout the month of April of that year, where they elicited a range of responses to go with those who protested the erection of this billboard in the first place.