Daphne Marlatt’s Then Now was published by Talonbooks in 2021

The following conversation is an edited version of the twelve-thousand-word transcription of four recorded 20- to 30-minute meetings that took place via Zoom in November 2021 when Daphne Marlatt and I met to talk about the thinking behind and making of her most recent book, Then Now (Talonbooks, 2021). I think of what we present here as a review-in-conversation. As such, rather than move what we said toward the written, this conversation maintains its ties to speech, with its accompanying and endearing awkwardnesses during the process of articulation. With that, thank you for joining our conversation.

—Jami Macarty

Jami Macarty

Let’s start by talking about the progression from engaging with your father’s letters to the book Then Now.

Daphne Marlatt

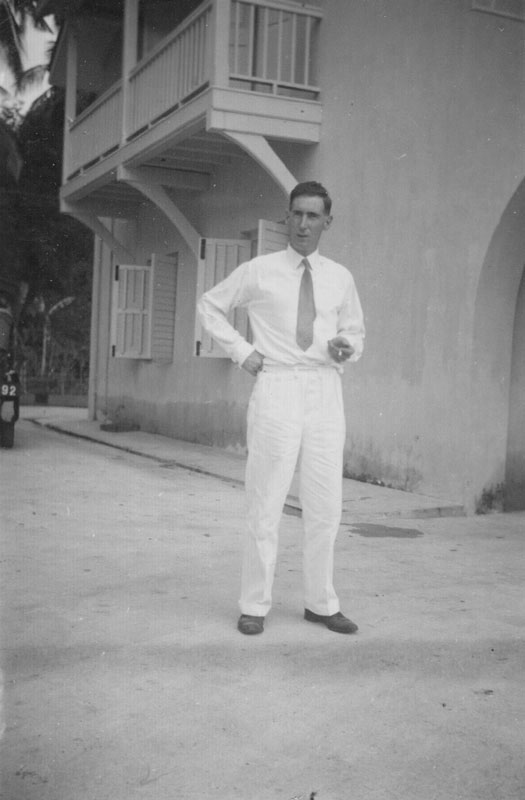

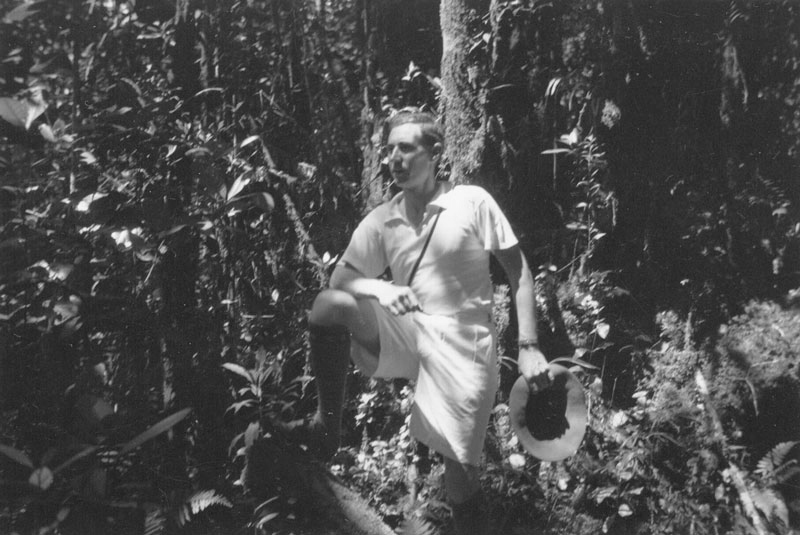

Quite a number of years before I read my father’s letters, my sister Pam gave me two big bags of family letters. I thought at the time, oh dear, when am I ever going to have the time to look at them. Then because my interest was triggered in Penang—I’d been back several times by then—I thought, I’ll look at my father’s early letters, the letters he wrote pre-war while there. They were so engaging I started typing up huge chunks of them for my two sisters. There were over a hundred pages that I sent off to them. After that, I started thinking about those letters a lot. My father’s voice was so alive. I was fascinated by his perceptions and what interested him.

JM

And the materiality of his paper and pen.

DM

Yes, the paper is so flimsy. And his handwriting. I thought, these aren’t going to survive, and I want his words to be present, recorded.

JM

When were you aware that you were making a book?

DM

At first, I was simply recording as much of the letters as I could. Then, I thought, I should do something with these. My first feeling was no, I don’t think I can because his voice is so distinctive and so much him.

JM

Can you track your thought, “I should do something with these”?

DM

Should I write a novel based on his letters? I thought, no, I don’t want to do that; I don’t have it in me to write a novel. Then I thought I could respond to some passages in the letters. That’s when I started trying to engage with some of the excerpts I’d typed up, seeing if I could write poems to them. You know, it was almost like taking one step, then another, and another. There was so much in my mind at each step; I had to be really careful what each next step would be. It was not so much about me, but about wanting to keep his words alive, not just in some archive somewhere.

JM

Can you say more about what led you to read your father’s pre-war Penang letters?

DM

In the bags of family letters there were letters from the 1950s, letters from North Vancouver to grandparents on my mother’s side. I didn’t want to read my childhood letters. It wasn’t the North Vancouver part I was interested in. It was the earlier times and why every time I go back to Penang I feel so at home. My body opens up. All the senses are so activated.

JM

Something about the place starts to generate something for you.

DM

Everything about the place—sights, smells, textures, its many different languages being spoken on the streets in George Town.

JM

What research did the book project prompt?

DM

I had to do a lot of historical research online. I had a couple of historical books from my dad. Stan Dragland and others gave me books. And when I was last there, I bought a beautiful book, Heritage Trees of Penang, which botanically names, has photographs, and little histories about the trees and their uses.

JM

Can you talk about the timing of the research and how the letters prompted your poems?

DM

I chose the excerpts of my dad’s letters first. Through that process I realized there was a narrative thread running through the book and I definitely wanted that thread that starts with his fascination with the colonial society in Penang and the place itself.

JM

I would describe the first section of Then Now as a responsive coupling of your short verse lines to your father’s letters from Penang.

DM

Yes, and I struggled to get the right tone because I didn’t want to sound like I was preaching to him from what was happening now environmentally. I basically censored myself when that came up and found another way of talking about whatever he was talking about. But there were certain points where I felt I had to say something that would give readers a sense of where I was writing from. Even though the pull of sentimental memory is very strong.

JM

What did you leave out or redact?

DM

In a letter about the fight between the woman next door and his own cook my dad used a racial slur, quoting what the cook said. That was obviously a swear word in use then, which I suppose the cook picked up from hearing the English of the people around him. It also spoke to the stratification of colonial society. That word was removed.

JM

Necessarily, elements of erasure and omission are compositionally prominent.

DM

Of course! I did have my sensor out for the comments that could be heard now as racist. I was most struck by the fact that there weren’t many of them; that my dad’s interest was so much there for the people and the cultures around him. It was a difficult book to put together; I was politically aware of the implications of bringing this book out now. I was actually quite anxious about it because I didn’t want it to be misread as another colonial toss-off.

JM

What else made the book difficult to put together?

DM

I wanted to bring out the intimacy in my responses, but I also wanted to refer to what was happening now, and what was about to happen there, then. It was a question of how can I be true both to what he’s saying and what I’m living right now. There were several different dimensions that I was juggling, and trying to find a balance between them was always the question.

JM

I can appreciate the socioeconomic, historic, and political aspects being balanced with the familial intimacy across three generations.

DM

I put in those few poems in the first section that refer to my childhood in Penang, my memories, then I took them out. Then, I thought, no, they have to be in there because that’s another dimension of it.

JM

Several excerpts of your father’s letters contain parentheses and other grammatical idiosyncrasies.

DM

I wanted to keep his voice. I didn’t want to tamper with it, because it was what had taken me so much by surprise.

JM

My experience of reading the book is one of tracking what your imagination was threading from your memories and your father’s letters.

DM

There are a number of passages where he’s describing what it physically and visually felt like to be there then. Those intrigued me and I included as many of them as I felt the novelistic line could tolerate without overburdening it.

JM

There’s a formal difference between your father’s writing and yours. He’s writing via the sentence, accumulation, and narrative. You’re writing in verse lines, compressed or extended, and lyrical.

DM

Yes, he’s conversational, casual, uses slang words of the time, and it’s all in a flow. I have this image of him sitting there at night, all these insects flying around, writing like he’s trying to get as much down as he can before he gets interrupted. I get a kind of all–in–a rush feeling from his letters.

JM

Immediate and present.

DM

He could be sardonic or ironic, especially when he’s talking about the political situation. My lines are not like that because I’m talking to him, but over this huge gap of his death and all the years since. I’m situating myself very much in the present in terms of climate change and environmental degradation, picking up on the political and economic implications of what has happened since the British Empire. I’m seeing human exploitation of the Earth as a kind of empire, particularly in the Western world. So, I’m poking at that and I’m thinking carefully. That’s why the short lines. I’m thinking about the implications of almost every word, certainly the politically loaded ones.

JM

Did you imagine the first section’s poems in short lines before they took form?

DM

I needed the condensation of time embodied in the short lines, because there was still that closeness to my dad, but there’s all that has happened since—not just personally, but for all of us, with the whole culture, the whole Earth.

JM

What was it like to meet your father from then, from before you were born?

DM

It was astonishing! There was this incredible sense of meeting this young man I’d never known. I could see the man he became in and through the letters. There was something in him that was able to so completely respond. That’s what I loved about the letters; that’s what I loved about the man.

JM

Were there things that you came to know about your father and your family from the letters that you didn’t know before?

DM

What springs to mind right away is my dad’s extraordinary sense of conviviality, the closeness among his friends that was obvious in his letters. This was not apparent in North Vancouver, partly because he was working and commuting for long hours here. And then there was the dislocation of immigrating to a very different social environment, plus his growing older. I also had no idea that he was as perceptive as he is about his locale, both the human locale and definitely the physical locale.

JM

What kind of responsibility did you feel toward your father, his letters, and your family as you were deciding what to excerpt, respond to, and write with?

DM

There was that sense of responsibility. It was so hard to choose just a few segments. So I changed my mind often. I had to balance what was humorous with what was really serious.

JM

It seems like that sense of responsibility shifted in “Memory Montage,” the book’s second section’s fourteen poems, where the point of view and the addressee shift.

DM

Yes, because except for one poem this section’s poems are addressed to no one in particular.

JM

This section’s point of view balances your father’s voice with your voice, the feminine, lyrical voice. Maybe the most striking thing in this section’s poems is their quality of the feminine; these poems centre on you, your sisters, your mother, and your amah. So another aspect of what is being balanced is gender.

DM

I love your way of reading it and I think it’s accurate. It took me quite a while to write the poem “A-mah.” When my father, my sister, and I went back to Penang in the 1970s—the first time I returned as an adult—we went to see her. She held our hands and was so openly happy to see us again. It was quite astonishing. I’ve always felt that there was something about her that triggered my interest in Buddhism. So I wanted to write about that.

JM

The poems in this section also expand your father’s individual narrative by adding the family narrative and focusing on the domestic.

DM

The domestic, of course, is what I most remember from my childhood. It all makes sense that way. I think the poem “A-mah” is really the pinnacle of the mothering that goes on in this section.

JM

Amah is a Malay word that describes an occupation, one that provides domestic help with children and household tasks to a family.

DM

Recovering a few Malay words was the most immediate pleasure because they came with a kind of aura around them from my childhood. There are so many different streams that I wanted sounded. There’s the acoustic stream, the sounds of words. Poetry, for me, is very densely made up of word sounds. They radiate in different ways, they radiate connections semantically, and they radiate connections aurally. Of course, there’s the whole memory layer that certain words come from, an idiom that is particular to a family and that family’s history.

JM

You name “acoustic memory” in the poem “stir / fry,” which takes place in the now of Vancouver’s Keefer Street, shopping for a meal’s ingredients, and also in Penang then, remembering that “flood tide of scent.”

DM

Right, an amalgam. I want to say something about the form of this poem. It owes a lot to Fred Wah and his way of moving through Music at the Heart of Thinking. I’ve always loved the way his lines just run. I mean they run at top speed with all sorts of connections coming up.

JM

The notions of “amalgam” and “connections” bring to mind the way the smells and sounds that we encounter in the present often draw us to the past. Can you talk about how sensory details reference then and bridge now?

DM

I would say that the second section is underpinned by then. The notion of “then now” was very much part of writing this whole section—how then is absolutely interwoven for me in the fabric of now. I think that’s probably a general immigrant experience. Whatever that family’s then or that person’s then, it’s interwoven, keeps surfacing, keeps surprising at moments in the now. I think “verbal pathways” had to be the book’s end poem because I wanted that sense of absolutely physical, located surprise at recognizing a rain tree here.

JM

The rain tree sends its roots, makes a verbal pathway through time and place—Penang and Vancouver—just as your father’s letters do within your life. The entire book is a verbal pathway!

DM

That’s true! I love sonic play. I think writing’s a matter of hearing, learning to hear the various levels in language, the various depths of meaning, the various radiating connections, semantically, phonetically, and chronically.

JM

I’m so glad that this book exists, that I read and have come to know it. It’s very special, and I thank you for talking with me about it.

DM

Jami, it’s wonderful to talk with such an intelligent reader. We’ve done a deep dive.

JM

Now to fitting the beautiful raw material that I think we have to our word limit.

DM

You won’t be able to do it, I don’t think. By the way, some of your questions were exactly mini reviews.