The following reflection of the exhibit lineages and land bases (Vancouver Art Gallery, 2020) by Tarah Hogue and Ashlee Conery is excerpted from Issue 3.44 (Summer, 2021) and has been altered slightly for online publication. Order a single copy of the issue or subscribe today to read the piece in its entirety.

…

Találsamkin Siyám Bill Williams¹⁰ alerted us to a book chapter by the art historian Kristina Huneault entitled “Listening: Nature and Personhood for Emily Carr and Sewinchelwet (Sophie Frank).” The chapter collects Huneault’s in-depth research that occurred in dialogue with Sewinchelwet’s living descendants and other Skwxwú7mesh community members over a period of three years. In it, Huneault laments that “despite considerable critical attention to Carr’s depictions of Indigenous subject matter, and a still more recent willingness to bring historical works of Northwest Coast art into conjunction with her paintings, there has been no substantive discussion of Frank’s basketry, still less a comparative analysis of the aesthetic concerns and productions of the two women.”¹¹

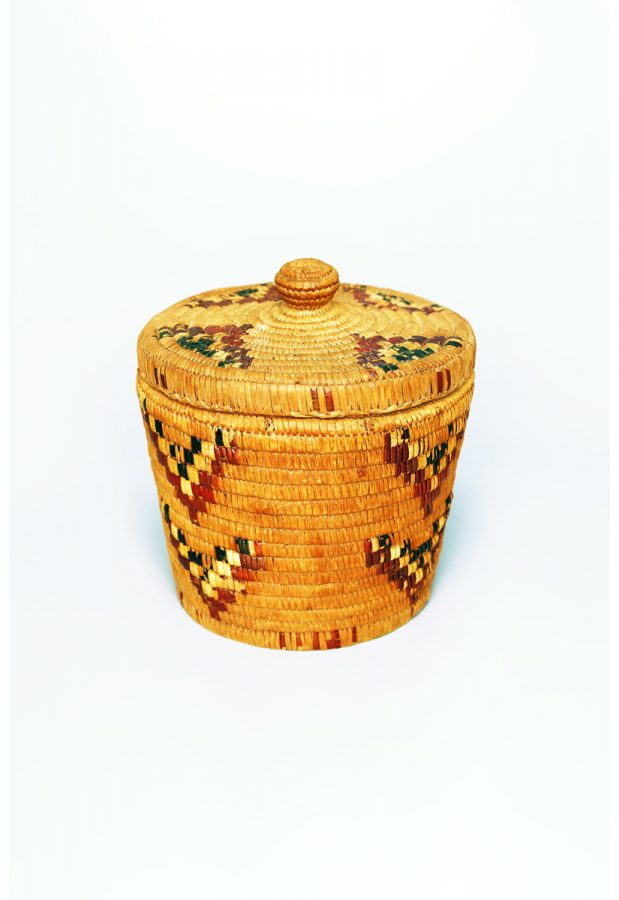

It is important to consider that the aesthetic terms to which Huneault refers when she discusses Sewinchelwet’s basketry are only partially available to a non-Indigenous audience unfamiliar with the techniques and motifs of Sewinchelwet’s community. Basketry encompasses a set of skills and specialized knowledge passed from one generation to the next. Teachings of the land figure prominently within this, as Sesemiya, a fifth-generation cedar weaver from the Skwxwú7mesh Úxwumixw, describes:

The knowledge of the materials aligns you with the landscape, and the ancestors know what the plants and animals and language of the place are about. It’s important to pray: to ask the creator to ask the ancestors to ask the cedar tree to share its wisdom. You have to go to the plant, to watch and learn from the plant over the course of the seasons. The plants are our teachers.¹²

Sesemiya is described by Huneault as an “attentive observer” of Sewinchelwet’s work: “For Williams, what particularly distinguishes Frank’s achievement is her sense of movement, visible in the unusual pinwheel motifs.”¹³ Sesemiya’s perspective on basketry enfolds a sense of continuity across species, wherein subjectivity and material expression extend well beyond human beings. The practice of weaving is a point of access into a worldview in which the maker is enmeshed within a creative, spiritual, and land-based lineage. At the same time, these practices are adaptable to changing contexts, as Sesemiya points out in Sewinchelwet’s combination of “Salish traditions with technical innovations intended to appeal to a Euro-Canadian clientele.”¹⁴

Huneault’s comparative analysis of Salish basketry — including a single basket securely attributed to Sewinchelwet — and Carr’s late oil on paper landscape paintings, produced after 1934, provided a framework for bringing these works into dialogue within the Gallery and posed multiple challenges that were responded to throughout the exhibition via contemporary artworks from the permanent collection.¹⁵ In “Listening,” Huneault asks, “how has women’s artistry brought them into contact with forests, fields, and oceans? And how have these contacts affected their senses of selfhood?”¹⁶ These questions were expanded in lineages and land bases to consider subjectivity beyond the human, and to “explore differing understandings of the self in relation to what is typically termed ‘the natural world.’” However, female artistry and selfhood remained at the exhibition’s centre, with a room at its midpoint (from any direction) in which Carr’s portrait, Sophie Frank (1914), catalyzed a reframing (following Huneault’s terms) of the histories and relations of Sewinchelwet and Carr.

■

¹⁰ “Találsamkin” is Bill Williams’ Skwxwú7mesh sníchim name, while “Siyám” translates to “Chief” in English.

¹¹ Huneault, 251.

¹² Quoted in Huneault, 276.

¹³ Huneault, 272.

¹⁴ Ibid.

¹⁵ These included, in one room of the exhibition, Liz Magor’s Beaver Man (1977/2010), Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun Letslo:tseitun’s Burying Another Face of Racism on First Nations Soil (1997), Jin-me Yoon’s A Group of 67 (1997), Jeff Wall’s The Pine on the Corner (1990), and Karin Bubaš’s Woman with Scorched Redwood (2007).

¹⁶ Huneault, 248.

This is an excerpt from Issue 3.44 (Summer, 2021). Order a single copy of the issue or subscribe today to read the piece in its entirety.