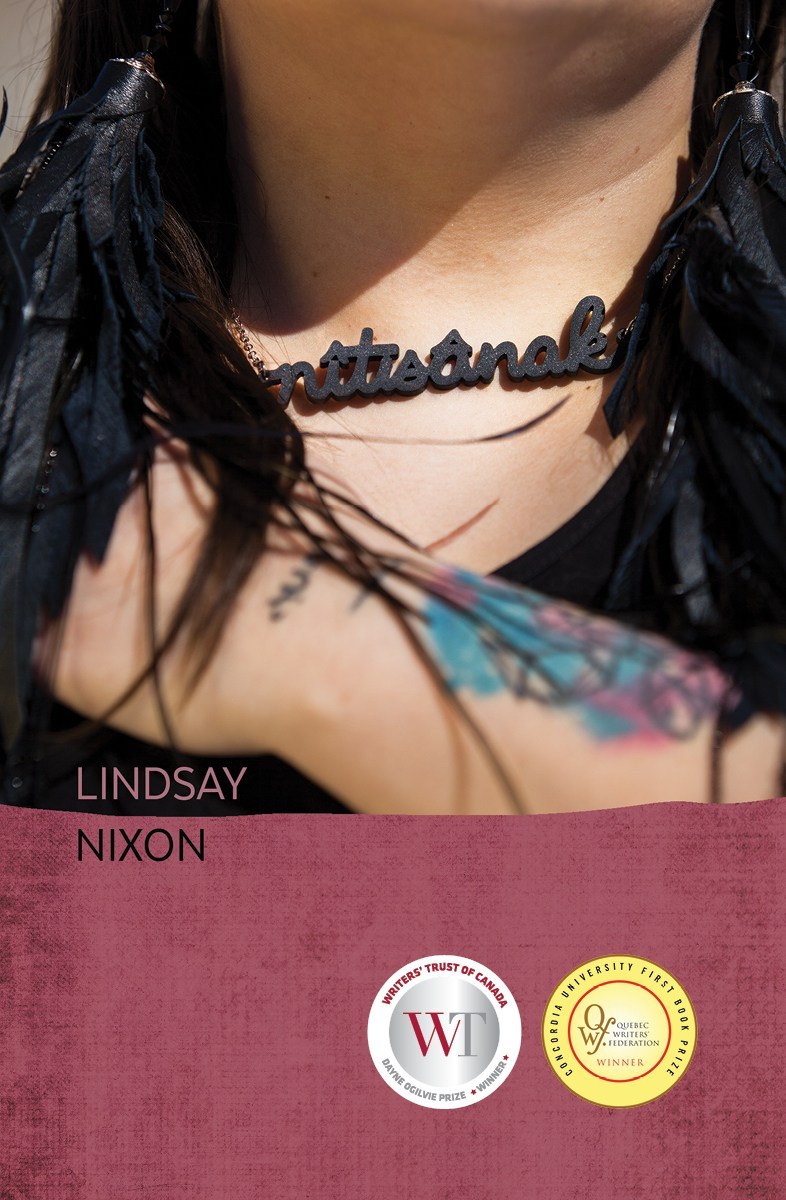

Lindsay Nixon’s nîtisânak is an accounting of beyond-family kinship, from the fragility of great-grandmothers to first gay makeouts. It feels like they are sitting next to you, visiting, talking round and round, pulling you in with familiarity and firmness. There are two relationships we cycle around: “B2B,” an abusive ex-love, and Nixon’s white mom who adopted them. Nixon’s roles in these two relationships shaped their nurturing hospitality and fierce tenderness.

The book allows Nixon to ask big and personal questions: what does it mean to have a white mom? And, what does it mean if your white mom does pills, but keeps it middle class fancy while busting her NDN kid for weed? It’s cliché to do pseudo philosophy in a memoir, but what sets Nixon apart is that they definitively answer their own questions: “There’s a particular kind of bravado that comes with threatening to call the cops on your Indigenous child because they’re holding weed. A bravado tied up in The Truth of the yt man, and an ideology that drug use is only illegal, wrong, and immoral on the prairies if it’s done by class-poor brown and Black people.”

The author has a self-clarity and a wondrous ability to weave theory into their memories, seamlessly. This is never more clear than in the twinned chapters “Bottoming” and “pihpihcêw,” when the sexiest thing anyone ever said to Nixon is paired with rigorous queer theory. It’s a love song to the communities that rarely get big time CanLit billing: prairie punk scenes, foster kid solidarity, urban NDNs. If you’re from these places, you’re dropped into nostalgic memories (the endnotes, especially, feel delightfully familiar); if you’re not, you are invited into scenes painted in emotive, musical detail.

The MVPs — “Prayer 9: for My NDN Bb Girls.” and “The Prairie Wind is Gay Af.”— are two chapters so lyrical they brought me to tears. Nixon has love affairs with cities; they know this is embarrassing: “I know it’s a sin to love the city you’re in,” they write about Montréal. But the prairies are more than a love affair. The prairies are the emotional core for Nixon’s genealogy: their first relative. This memoir is drenched in Chrystos and Missy Elliot, OG(kush) and messy bodies — Teenage Dirtbag, but as more than a passing aesthetic or a joke. Nixon’s deft way of weaving their love life into ruminations on trans masculinities, violent policing, or feminism remind us that we’re hearing an ethics of kinship be articulated.

nîtisânak is wildly interesting, thoughtful, and tender, but also utterly uncompromising. Nixon sees through the needs of a hungry audience who may have come to this queer Indigenous memoir to be titillated or scandalized and gently refuses. As they say, “Consider this reminder, dear reader: thank you for reading, but, while I feel no pressure to hide my pain from you and ground my story in neoliberalism, I don’t owe you my pain.”

This book is a litany of running away, but isn’t despairing; Nixon finds a home with nîtisânak, which means “siblings,” a non-gendered term in Cree. The possibility of Indigiqueer kinship is a salve for the wounds from the other promising but ultimately disappointing homes they try out. These are the kinships, both toxic and tender, that created Lindsay Nixon.

***

Jessie Loyer’s review of Lindsay Nixon’s nîtisânak is featured in Issue 3.42: Translingual (Fall 2020). To read the issue in its entirety purchase a copy here or subscribe today to receive this issue plus two more delivered to your door.