Deanna Fong

It was a bit of a path to get here, but I’m happy that we’re finally getting a chance to talk. It’s been amazing assembling a community around your text, “Journal from Roy’s,” over the past few months—which has meant, of course, also assembling a community around Roy Kiyooka’s work. I wanted to begin by asking how this text came into being and what your relationship with Kiyooka was like.

Gerry Shikatani

I became aware of Roy’s work quite a few years ago. I had already been reading his writing and seeing his artwork, which I was really fascinated and so impressed by. He was also connected to a non-Japanese or non-Asian-Canadian community, who were mainly part of the TISH group. bpNichol was out that way as well in those days. It just seemed really kind of a natural thing.

If Roy was going to read anywhere in Toronto back in the ‘80s, it was at A-Space gallery, because they had a relationship. I met Roy for the first time when he came to Toronto to read at A-Space. I also met Daphne Marlatt at that time because she came and read there. I was still in university in the mid-to-late ‘70s and A-Space’s café had started already. People like Victor Coleman were involved. The whole group from out west. So, from that I got to know Roy, and we communicated quite a bit.

I finally went to read in BC in 1986 when I was in my thirties. I had never made it out there before that, but at the same time, I knew I had a readership and following out there—much more dedicated than in Toronto or Montreal, actually, which is why I ended up reading out there so often. In ’86 I did a reading tour across Canada that started in Vancouver, and Roy said right away, “Come stay at my place.” There was a warm invitation from him at that time. We had started a dialogue through emails and letters. That was really exciting because he lived in Strathcona, which I knew about because of my mother told me all about growing up in that area when I was a kid. She was a great storyteller. So, I came into Strathcona for my first time, and I was just marching up the street with my bags, excitedly counting off the names of these streets that I knew—that I’d dreamed about it since I was a kid. So that was the beginning.

I remember calling my mother at home and she ended up speaking to Roy on telephone. I could see that Roy had a very similar relationship with his mother, as you see in his Mothertalk book, in his very precise way of enunciating his Japanese. [1] It was very respectful and soft—exactly how I would speak to an older Japanese person. There were just unstated things like that that connected to my experience.

Right away I was immersed into his place and all the people he knew, like Trudy Rubenfeld and Rhoda Rosenfeld, and Maxine Gadd. And, of course, the Japanese-Canadian Tonari Gumi group and Takeo Yamashiro the shakuhachi player. When CBC Radio program anthology came out with Paper Doors poets, I had gotten to know Takeo, and he played some of the music which I produced for the Nexus Improvisational Percussion Group. So, I was coming home to all these groups in this place I had never been before. It was all just very comfortable.

DF

So, you mentioned bpNichol, Daphne Marlatt, Maxine Gadd, Trudy and Rhoda—many writers and artists whose works have been featured in the pages of TCR because of its interest in experimental writing. Following on that, I wanted to ask you how the notion of the experimental or perhaps the interdisciplinary figure into both your work and Kiyooka’s work, as you see it.

GS

Well, one of the things which influenced me was this this notion of “making art,” which is a term that I used when I taught creative writing at Concordia and York University. In making art you work with certain materials. Once you open that up, then you get into this whole other way of making. You have to have proficiency. It’s not just “do whatever you want” because that becomes pretty chaotic and it’s not necessarily good—although it can be good—but you have to at least have a proficiency with the particular materials that you’re working with. Materiality is really important.

DF

Whether that’s language, or paint, or film, or sound—whatever, right?

GS

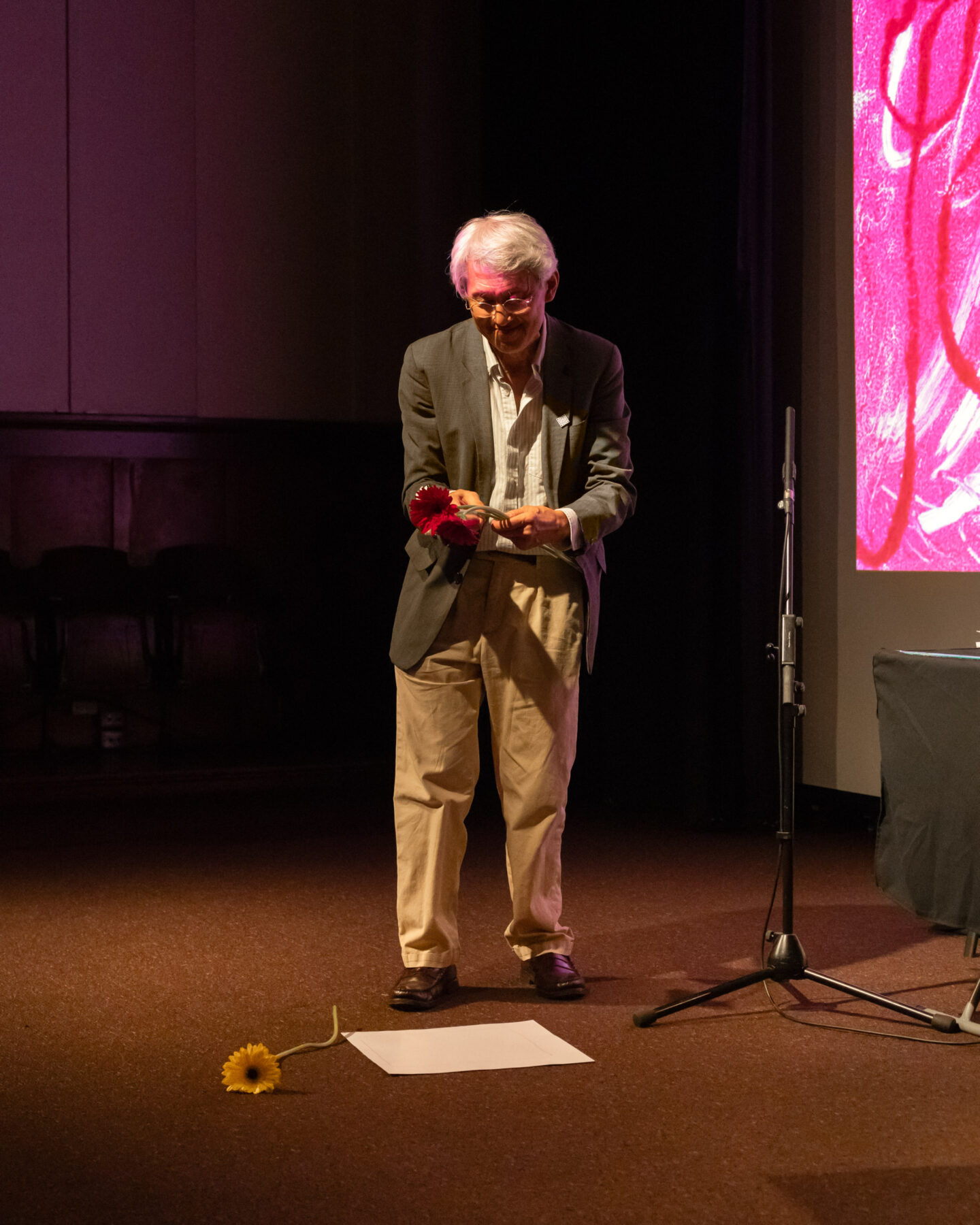

Yes, and to a certain extent in the mixing of media as well, without even having the proficiency in certain media. I think there’s a responsibility there. I feel that I can handle multimedia work or intermedia work because it’s part of something that has been really important to me, which is the notion of collage. Even performance, for me, is about that. When I performed at Western Front, I knew the program of what I was going read, but I didn’t know how I was going do it until I started walking the streets before the show. [2] Then I decided what I had to go and buy for the props.

I’ve realized within this plastic thing called a performance that you can break so many things. In a lot of ways, its goal is to unseat a public—but also myself. You do improvisation in a space with materials. Writing works when you’re thinking conceptually about materials, about the language itself. Then you see something astonishing. You don’t know exactly why, but it’s the interaction of the place with the material world and the sensory world that can create these moments of what I would call ellipsis—new ways of experiencing that thing beyond, they say, the text itself.

DF

Yes. That’s something that I wanted to ask you about: there’s a concreteness in your work in the ways that you describe places, events, and objects in the world. But there’s also an interest in the concreteness of language—the way that you play with not only sound, but also typography in your work. There’s such attention to typographical markers as meaning-making elements in your oeuvre. So, just a very broad question, I was wondering how these two kinds of materiality interact with one another—the materiality of sound and the materiality of marks on the page— to shape the concreteness of the things that you bring into the collage of your world.

GS

Right. Well, I guess you can’t really go any further beyond your sensory perception that creates whatever work you’re going to do. Words are conceptually based—they’re semantic and all that—but I also follow bpNichol when he talks about composition by sound.

DF

“By ear, he sd.” [3]

GS

Yeah, it’s by ear, which I believe in. It’s a strange thing comes into your head—sound, and at the same time a word, which is a marker, a marking, which then gets transformed from a concept into something else because it triggers this oral relationship, which is interior. It creates all these kinds of sculptural spaces. That’s the interesting thing with installation: the concreteness of language, in the marking of the page and the typography, creates a kind of interior installation space.

DF

Wow. I love that.

GS

That’s where I get into the whole thing about kinetics, because then movement comes from that. When Eric Schmaltz talks about kinetics in my work, that’s what it is. It’s the energy, the wavelengths, the sparks that are going on. When something works, one never knows exactly why. But it creates a new kind of amazing or astonishing thing. There is new perception in these small little things that happen externally. Even the flatness of things is a place of stillness. My interest in this comes from a religious basis—because I studied religions—this idea of getting to the still point, which is also very noisy [both laugh]. They’re the same thing. It’s just all absentmindedness; it forgets something. And then you move on.

DF

Is this noisy stillness the centre point from which your improvisational inspiration comes from?

GS

Yes. I think for most people, that’s where something exciting happens—or maybe doesn’t happen. But they’re in the middle of an experience and everything’s progressing, but within that there’s a momentary silence that becomes a still point, in a religious terminology, which is moving but doesn’t move. Within one’s person this takes the form of different little awarenesses going on. And then you move on.

DF

So, compositionally speaking, there’s this interior installation space as you’re composing the work, in which you’re bringing different elements in—you’re improvising, you’re experimenting, you’re opening, you have great receptivity to the things around you that also create the work. I’m interested, too, in how that improvisational or let’s say that that kinetic space connects to the person who then receives the work. That has to be a totally different constellation of meaning-making things.

GS

It’s hard for me to say exactly how that’s going to happen. All I can say is I create a proposition of saying: this thing, and these objects, and this perception. Does it work for somebody? These things are always mysterious to me. If I’m reading somebody’s work or looking at their art, why does it work? What is the harmony I see in the things? Because they can be totally unrelated, conceptually, but for some reason it works because you make that little shift. It’s like that “Aha!” moment, you know?

One of the interesting things in provocative art is that somehow the artists have figured out the thing to create an openness for people. I did this in Regina years ago when I was working on my Eastern White Pine project: I created barbecue sauce from it. I made tea from it. I’ve done that in performance.

Then there was the intermission, and Steve Smith was hosting, so I called him on phone so that people could hear me. I wanted my phone call to him to become part of the performance, because I wanted people to know that I was out there doing something. I bought some snacks for people and then gave them snacks to eat [both laugh]. I had this idea that when I took my break, I was going to get some food.

Or even false endings, which I remember doing in Paris at Centre Pompidou was where I end a work, and then I’d march really fast off the stage and people would have no idea what was happening. Then I eventually I’d come back and restart doing something else. Therefore, I created a new, different ending.

Through all this, too, there is attention to the sounds I’m using, and also the imagery and objects, that I use—for instance, something I use often is a broom. I’ve used things like plants and flowers because I really like flowers. It’s nice to have these things as setup, so people can look at them and enjoy them, you know? In that performance at Western Front, I was mimicking bringing flowers to my mother’s grave, to my parents’ graves. I brought flowers because that’s how I ended that piece. I just thought of while I was out, “Well, I’m reading that thing, why not actually bring flowers and create a ritual kind of situation?”

So, I do all those things, and the end result . . . What is it? What happens? Is it great? I have no idea. Maybe it doesn’t make sense, but those are the kinds of things I’m interested in doing.

DF

I have to say, for me, it was an experience of great joy when I got to introduce you at that reading and got to be involved in the performance that way. I got to play. I expected to go on stage and just give this rote introduction of your accolades and your books. Then all the sudden I was transported into this space where we were just riffing together, and it was such a delight.

GS

Oh, good. I figured that. Obviously, the audience saw me creeping in there as you were speaking. Therefore, there was not just one centre of attraction, there were two. So, what do I do with this composition that people are seeing? It becomes a sound composition as well for me.

DF

There’s this really wonderful “spilling over the container” in your work in every sense—whether you try to define it by genre, or you try to define it by its meaning-making modes, there’s a certain exuberant excess that I really dig.

GS

It comes down to the words, too, because these things I’m doing are written. That’s the other thing about being concrete. In a different kind of way, it’s not to mimic the thing, but to create the language in a whole different hemisphere with different sensory experiences going on. It’s not talking about the concepts of the word as much as a sensory experience that’s being created, layered into it.

DF

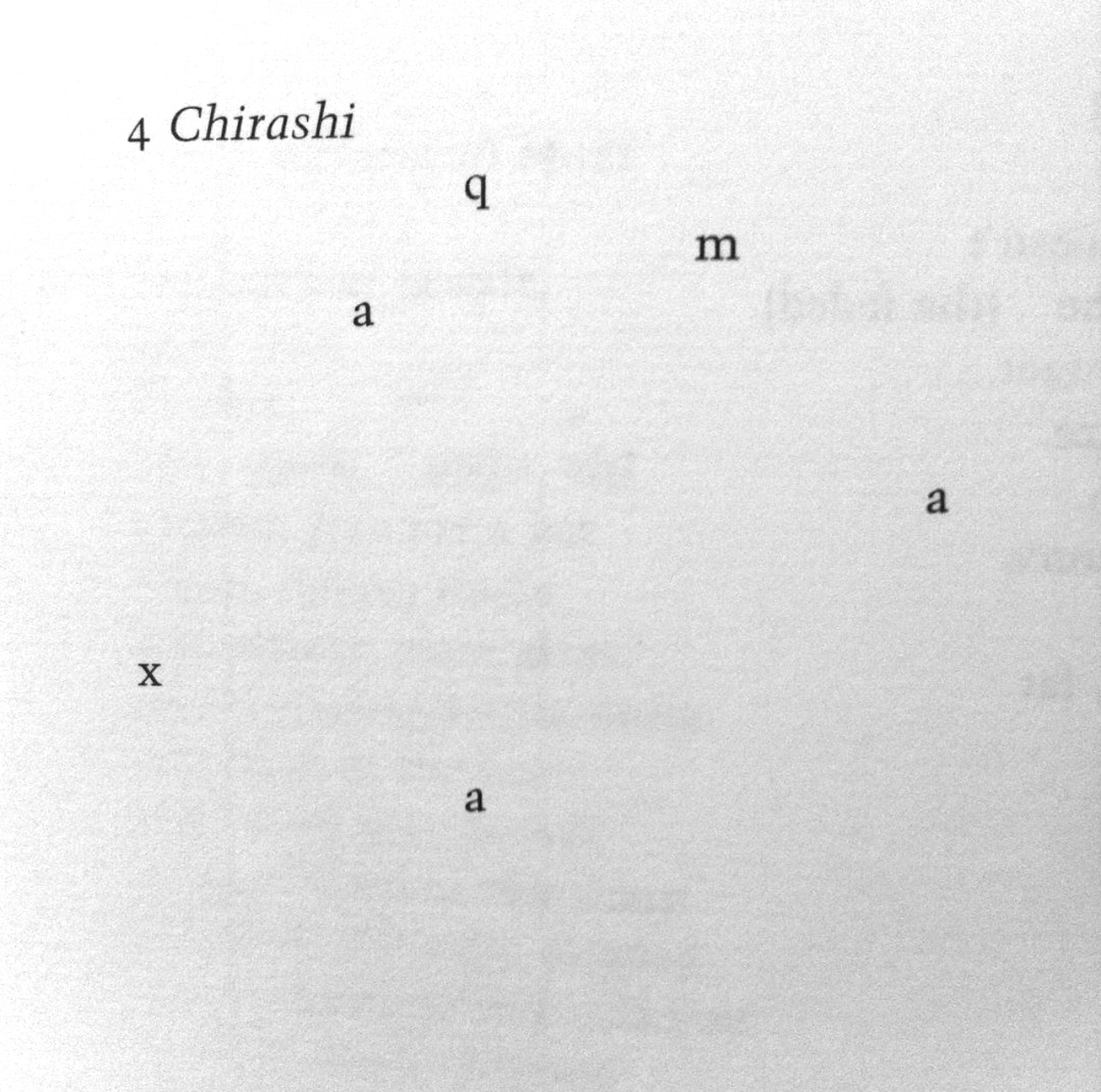

This brings to mind that piece of yours that’s talking about the sushi restaurant and then it’s got the chirashi poem, with its consonants scattered across the plate, which is the page. I love that concreteness. As a reader, it makes you encounter the scene in such a different but very real way.

GS

And when I perform it, I go into a flamenco thing with an olé! in it [both laugh]. Flamenco is full of improvisation, too, and flamenco singing—which I love, and I’m so used to hearing—is also part of also my sensibility now. I think that in artwork, or the making of things, whether they work or not doesn’t really matter for me, as long as you present in a concrete way. Concreteness means putting people into a space where they have an opportunity to travel, in a certain way.

DF

To be transported, as it were, like I was. So you create a set of circumstances in which something may or may not happen. Something no doubt will happen, whether it’s the thing you intend or not. This makes me think about a recording of Kiyooka’s where he’s talking about the audience for his work. This is after he’s left painting, and he’s decided to move into media that he feels are better modes of personal expression. I remember him saying that he considers the audience of his work about 12 people who are his close friends. So, I was wondering, who do you consider the audience for your work?

GS

It’s very hard for me to figure out. I don’t really know. It’s not in the same way as Roy because he knew the audience, and because he was so much in community. I’m not.

DF

You’re not?

GS

I don’t think I am. Not really. I do have good friends and we’re familiar each other’s work, but it’s not in the same kind of way when I’m doing these things, in that I’m thinking about certain people. It really isn’t. What I’m interested in is trying to invite anybody into that space.

I interviewed Ferran Adrià, one of the world’s most famous chefs in the last 50 years in Spain, and he talked to me about sushi. He said, “What is that experience of somebody tasting something they’ve never known before? What is that moment?”

I think about these kinds of things in a similar way. An experience is not going to be repeated because you’re only in that space for a certain period of time. It’s really fixed, much like a gestural piece of art. It’s there and you can look at it, be inspired by it, like it or not like it. But it’s that one point that the artist has invited you into that moment of concrete experience. I do this hoping that I’m being faithful to an audience—whoever the audience is; that I’m being honest, and that maybe this will be interesting or fascinating for some people.

That’s the main thing I hope for: that I’m doing service to a world of objects and sensory experiences that we have as human beings. They come out of me, but they’re not necessarily autobiographical; they are channels in which people can move into different areas of experience and association and be part of this energy dynamic that creates sparks from one medium to another, one thought to another.

DF

Yes. The novelty of a sensory experience, whether that comes to you through food, or through the experience of a poem, or a great work of visual art. That like arresting moment where you’re like, “I have never felt this way before.”

GS

I’ve always been excited about that in other people’s work. So, I guess I’m trying to do the same kind of thing, while respecting certain kinds of traditions. For example, I’m interested in costumes, because Flamenco artists, usually when they’re doing a show, they wear jackets and suits. So do jazz musicians, which I’ve always liked from the old days, the ‘50s. One of my very close friends in Paris is an amazing jazz musician, and they always dress up because you honour the audience by doing that, rather than being the intellectual poet with a run-down, worn-out corduroy sport jacket [both laugh].

DF

The one with the elbow patches.

GS

Right. Those things fall into certain traditions, which I really like. These are the things which I like to maintain as part of still this tradition in art where there’s real respect for where you are. The potential of where you are for anybody. Everywhere, in any space, there’s an opportunity for opening one’s mind and thinking in terms of experience.

DF

Absolutely.

GS

That’s the whole thing about collage. You’re writing something, then something goes off over here and you see a poster from this or that and it makes its way in. One’s life is made up of all those leaps that form part of a whole day. For me, it’s a way of consecrating everybody’s way of forming their day. There’s all this improvisation going on. This is what it is for most people.

DF

When I was speaking with Henry Tsang about his contribution to this project the other day, we were talking about Jesse Nishihata’s film that Henry is working with, and this brought us into talking about Kiyooka’s documentary practices, in which he would just bring the tape recorder around and just record everything that was going on. There’s a quotation from a manuscript that was never published called Laughter, in which he says, “Every event is its own artifact. It doesn’t need to go through an artifice to become something.” So, when you talk about the aesthetic of the collage and trying to represent with fidelity the experience of being a sensory being moving through the world, it has a little bit of that flavour, too. This Brechtian flavour, where whatever you’re doing already is the performance. It already is the poem. Does that resonate?

GS

It does. One of the things I wrote about after Roy passed away is his movements: wiping his table, making the coffee, the sweep of his arm . . . Those small gestures of everyday life. Everybody has these things and when I can honour them, it’s extraordinary.

DF

I wanted to pick up on something that we talked about last time we spoke, which is this idea of a personal language or a personal mode of expression. I was wondering if that’s tied in with this experience of creating a kind of concrete encounter.

GS

Hmm. I guess it could, but I’m not sure. For me, personal language is something that evolves through school and these kinds of things, but it’s also about the languages you speak. Another thing I wrote, which I haven’t published yet, is about maternal language or umbilical language. We all have certain degree of memory of the first sounds that we used for eating, for making noise, and for music. I think that’s left in our bodies, whether we use the same languages or not, and forms a strong basis of the language we have.

I think we’re often trying to make something that expresses and articulates that. Shows it off. For me, that’s connected to the Japanese language, because when I was in Japan, I was very comfortable.

Even though I can’t read or write, people from Japan thought I was Japanese. It was because of my movements and the way I expressed myself. The utterances and the breathing. I think I ended up doing these things often because there was something I couldn’t really express in the English language—not because I wasn’t literate enough, but because there was no way of expressing certain things. That comes out in the Japanese, “Ahhh.” Japanese is so onomatopoeic. We have all these different sounds. Myself and my siblings, we talk about this often about certain words in Japanese we use, that there’s no word in English that satisfies. Even being in hospitals—I remember talking to my mother about this—they ask you to describe a certain pain. “What number what number would you give it from 1 to 10?” [both laugh].

DF

So inadequate.

GS

It doesn’t describe pain. There’s a word in Japanese that describes a certain kind of throb. I arrive at the failure of that. But I just move on to something else. There is always a degree of replacement that I’m doing because English isn’t sufficient. There’s a whole area between the two languages where I exist. And since that time, French and Spanish have come to also become part of the things that I use to replace it, which is why in some of the sound pieces I do, I use the four languages. It’s incredible because some of those words are very similar from Spanish, to French, to English—the sound of the words. It’s so easy to compose from that.

DF

There was one more thing that I wanted to ask you before we close, which is if you could tell us a little bit about Jesse Nishihata’s film, which features both you and Roy Kiyooka. How did that film come about?

GS

Jesse became a good friend of mine when he was still working at CBC and doing stuff at NFB. That’s when he wrote that film called Bird of Passage, which is about the Japanese-Canadian evacuation during the Second World War. [4] I went to see him, got to know him, and he became a good friend. We talked often and he had this project of asking people—not necessarily filmmakers—“Do you want to make a film? What do you want to do?” And so, he says, “I’ll get you the film crew and we’ll do it.” I decided I wanted to go to BC and search for my personal and family roots, because they’re way up in the Pacific Northwest, from when they evacuation came. My older siblings were born in ghost-town internment camps. I have one brother who was born in Toronto after they came east, then I was the last one. So, I said, “I want to go and see that place. I want to go see BC, where they came from.”

Being born in Toronto, us two younger brothers, we were disconnected from that. So that’s how it started. But then I realized that I also wanted to go back to the family stories or the narrative. Part of that, especially, was the geography, the landscape. In going through that, I realized that what I was trying to explore was, “Where do I get my personal language?” It’s that same thesis where I start at birth, hearing Japanese lullabies. My first thirst, first hunger, were all in Japanese. But then after that, the rest of my life was also in that landscape through what happened to my siblings and my family, because that was their story, too. Being in that place meant that we received so many new experiences, physically, naturally, mentally, emotionally.

It was a way of inspecting all that and trying to put it together. That’s what the film was about. Then Jesse realized that I knew Roy, of course, because I was staying at Roy’s when I went there. That’s why Jesse brought the crew and started to film us.

In hearing Roy talk about going to Japan and the way he related to his Japanese self, and his feelings of being very close to people over there, I saw myself, in a good way. I had a lot of things in common with Roy. Like I said, the way he spoke to my mother on the phone was really astonishing.

DF

That’s a beautiful astonishment. [Pause]

I feel breathless [both laugh]. I just love this conversation. In the same way that it’s impossible to describe certain sensory things in language, I feel that the sum of this discussion, in all its different pathways, is that I’m getting just a tiny bit closer to being able to articulate something about the ethos of your work that I have appreciated for so long.

[1] Roy Kiyooka, Life Stories of Mary Kiyoshi Kiyooka (Edmonton: NeWest Press, 1997).

[2] Dear Friends &: Reading with Tina Do, Rhoda Rosenfeld, and Gerry Shikatani, hosted by The Capilano Review and Western Front, Grand Luxe Hall, September 5, 2024, https://westernfront.ca/archives/get/ca_occurrences/3278.

[3] Charles Olson, The Maximus Poems, Ed. George F. Butterick (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), 6.

[4] Bird of Passage, directed by Martin Defalco, written by Jesse Nishihata, National Film Board, 1966, https://www.nfb.ca/film/bird-of-passage/.