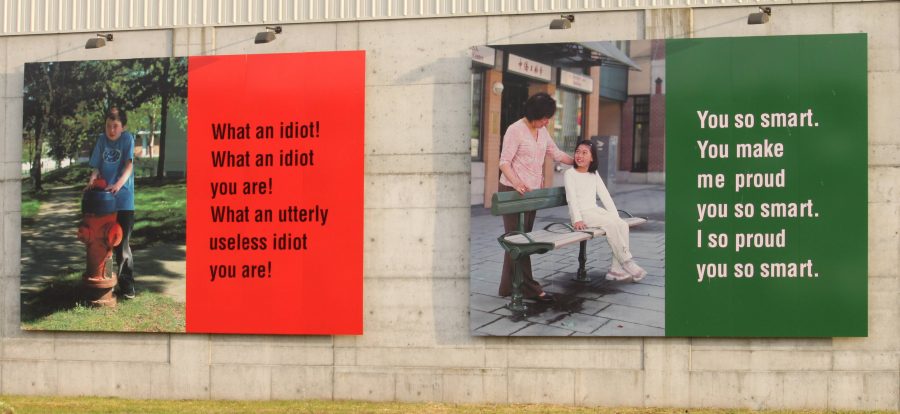

I first met Ken Lum in 2005, when working at Centre A gallery in its former location at 2 West Hastings. After closing the gallery one spring afternoon, my colleagues and I had walked south to the opening of his public artwork, A Tale of Two Children: A Work for Strathcona, on Produce Row at the city’s National Yard. As part of Lum’s Portrait-Repeated Text Series, these two panels — each with a photograph on one side, and text on the other — juxtapose two different childhood fates, depending on the voices internalized. One shows an unhappy Caucasian boy, alone, hunched against a fire hydrant, alongside the text: “What an idiot! What an idiot you are! What an utterly useless idiot you are!” In the other, a young Asian girl smiles, relaxed, looking up to an older woman, beside the phrase: “You so smart. You make me proud you so smart. I so proud you so smart.” The body language is revealing, but it is the text — with its charged colours and repetition — that complicate the picture’s meaning, raising issues of class, ethnicity, gender, and upbringing in the mind of the viewer. As we stood on the grass near the piece, Ken told me how he grew up nearby and that his mother, who emigrated from Guangzhou to Vancouver a day before Ken was born, worked at Keefer Laundry, where her exposure to laundering chemicals may have led to her early passing from leukaemia.¹

In the same frank and accessible ways, Lum seamlessly interweaves autobiography in Everything is Relevant — a collection of his writings on art and life over the past three decades that demonstrates his commitment to pushing boundaries in contemporary art and engaging with a growing community of contemporary artists and intellectuals speaking from diasporic experiences and the so-called margins. The book looks back on his journey, from a first generation Cantonese-Canadian child raised in poverty to a science student completely taken by contemporary art in university; from his critiques of Canadian cultural policy and identity debates as an artist and professor of colour to his international posts as an artist, teacher, curator, and journal editor during the contemporary art world’s globalization from the 1990s onward. This journey took him from London and Paris to D’akar, Martinique and Sharjah to Hong Kong, Hangzhou, Beijing, and Japan with stops in Toronto, Saskatchewan, Winnipeg, and home to Vancouver in between — a peripatetic travel pattern not possible in our current pandemic times, and far less realistic now given our present climate crisis. The last third of the book charts Lum’s move to Philadelphia to become a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Design, and his persistent critical questioning of and experimentation with art in public space — specifically, how public memory can act as future speculation at a time when colonial monuments are being toppled. Ken will always be one of Vancouver’s greats: an artist who defied expectations of his working-class, immigrant background to become an internationally renowned artist and passionate critic of contemporary art, and whose important contributions to the field were in many ways ahead of his time.

■

“One of my interests as an artist and teacher is how institutions today frame art in ways that ignore or subjugate the question of difference,” Lum writes at the book’s opening.² This question of difference propels Lum’s practice and is inflected throughout the book. The strongest pieces are his most personal, where he draws from lived experience to analyze, dissect, and question identity formation in relation to external perception, buoyed by the ambitions of postcolonial theory to challenge Western universal worldviews.

In “Seven Moments in the Life of a Chinese Canadian Artist,” 1997, written for Hou Hanru and Hans Ulrich Obrist’s internationally travelling exhibition Cities on the Move, Lum recounts moments of prejudice and misrecognition. During introductions at a dinner in France, one artist looks surprised, exclaiming to him: “Why, I did not know you were Asian. Your work looks like it could have been made by a non-oriental.” Ironically, during a protest at the Vancouver Art Gallery advocating for greater representation of visible minority artists in its exhibition programming, Lum and Stan Douglas are cited by a Gallery curator as proof of its commitment to this, followed by several voices shouting that they no longer considered them artists of colour. At a dinner in Montréal with several Chinese artists, someone remarks in Cantonese how great it is to have so many Chinese artists together. One artist, not knowing Ken could understand Cantonese, replies, “Well, Ken Lum cannot even read Chinese.”³

It was this absence of belonging that led Lum to explore questions of identity and difference across global contexts. Writing on the Dak’Art Biennale of 1998 in Senegal for Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art, Lum pinpoints the imperialist tendencies of how “[o]ver and over again, the development of Western art is predicated on claiming non-Western art forms for itself.” Yet he also points to “the multiplicity of modernities in the world,” such as Dak’Art itself, and the need to let go of Euro-American concepts of art in understanding perspectives beyond the so-called West.⁴ Revisiting Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa for the same journal in 1999, Lum critiques past art historical interpretations of this painting while providing a decolonial dissection of it as a “liminal picture,” seeing resilience and potential where normative social hierarchies have collapsed. He writes: “Although the depicted scene is a tragic one, the grouping of bodies on the raft can be read unitarily as a community.”⁵ Addressing this “interlocked structure of interchangeable and multiple identities,” Lum focuses on Géricault’s dislodging of racial and masculine sexual identities from fixed meanings of the time; notably, the black male figure at the painting’s apex is an expression of unspoken social truths: “the composition of the human pyramid aboard the raft is meant to mirror the social composition of France’s apparatus of empire, built to a large extent as it was on the backs of male African slaves.”⁶ Lum saw in Géricault’s artistic strategies a new subjectivity of alterity amidst crisis—“the idea that difference and individuation do not threaten the whole, but may even advance it.”⁷

Lum’s deep intellectual curiosity and fervent belief in persisting against colonialism to hold space for diverse perspectives and representations — to dissolve the imaginary construct of the “Other” as aptly theorized in Edward Said’s Orientalism — remains inspiring, particularly at a time of rising xenophobia simultaneous with protests for racial and social justice worldwide. In Lum’s inaugural editorial for Yishu: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art in 2002, he reflects on the history of Western imperialism in China from the Opium Wars of 1840 onward, which produced in China an identity crisis and a complex manifestation of modernity. Observing the contemporary art world’s increased attraction to perspectives of alterity and diversity alongside its neocolonial entanglements with the marketplace and global capital power relations, Lum calls for a genuine openness to cultural difference: “Only after claims to cultural fixity are dislodged can a mutual interrogation of traditions and alternative modes of conduct be possible, and only then can a dialogic democracy be developed, one of which is based on the authenticity of the other.”⁸

By 2005, Lum’s weariness towards the art world is apparent: the dissonance between his work as associate curator of Sharjah International Biennale 7: Belonging — managing high-maintenance artists, meeting with Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi, the Biennale’s director, and coordinating the arrivals of art world cognoscenti — stands in stark contrast with nearby geopolitical strife. During the Biennale’s installation, he notes how a local newspaper headline, “Car bomb at Qatar theatre kills Briton, wounds 12,” sits beside an advertisement of a massive five-star residential development being built on a nearby articial island. At the Biennale’s opening night party, he looks across the water thinking, “to the north, on my left, a war rages in Iraq.”⁹

In his curatorial text for the Sharjah Biennale, “Unfolding Identities,” Lum questions — as he simultaneously lives — the trope of nomadism that had become increasingly popular in discussions around globalization, mobility, and the role of artists as figures of creative resistance as they transcend borders. Situating the nomad’s theoretical and idealized characterizations — notably by male intellectuals including Henri Lefebvre, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Homi Bhaba, and Arjun Appardurai — in relation to the hard realities of migrants and refugees forced from their homes and across borders, he exposes the “artist as nomad” rhetoric as one of privilege and power, abstract, and romanticized: “Nomadology as a tool to theorize the multiple means by which travelling individuals negotiate and renegotiate subject positions in the context of codifications of family and community groups, gender, skin colour, economic and social class, and nation states is useful but problematic in terms of the often devastating psychological and physical damage borne by these same individuals during the very process of negotiating subject positions.”¹⁰ He goes on to describe the stress, loneliness, powerlessness, and feelings of exclusion that this metaphor of the nomad neglects to register. Yet feelings are exactly what art can affect, Lum insists, particularly in sites of the so-called periphery, where artists are freer from entrenched art systems. He closes with a personal and revealing statement: “Artists also long to belong, but the curse and saving grace of art are that it can never entirely belong.”¹¹

■

Deep existential crises can beget great writing. In “Something’s Missing” (2006), Lum candidly reveals that the past eight years “was a time when I felt great disillusionment about art and great disappointment in myself, a crisis of being that I believe afflicts all artists from time to time.” This very crisis brought him to the margins of the art world, searching for answers. Lum reflects, “I had a choice: I could either stop being an artist or I could enlarge my frame of understanding of art by looking away from what I was accustomed to.”¹² To become re-enchanted with art’s purpose, he sought a more philosophical view of art through his everyday life, letting go of the art world’s expectations and all its limitations, and widening his ideas of what contemporary art could be and who could participate. We seldom hear from mentors how hard it has been for them, so this passage is particularly striking.

Three moments in Everything is Relevant stand out as igniting Lum’s core artistic inquiries — moments of existential questioning where he finds stillness and inspiration on the spectrum of alienation and belonging. The first is an early diaristic piece, Home (1993), where he muses how “a home can be created out of just about anything. Home can be a shack built from refuse. Home can be the space under a viaduct or bridge… the problem is not even so much about the idea of home as it is about the ideal of home, which is rooted in an ideology of the home.”¹³ In his Furniture Sculptures (1978-present), composed of rented couches turned inward to obstruct the viewer from their function, Lum brilliantly locates the boundaries of private and public space and questions the nature of access and class, while cleverly poking fun at minimalist sculpture and bourgeois ideas of taste. In There is no place like home (2000), a large-scale billboard of six Portrait-Text works presented outside the Vienna Kunsthalle and depicting a range of social types responding to ideas of home in a multicultural society, Lum transposes these questions of belonging internationally in the contexts of immigration, citizenship, and nation.¹⁴

A second moment occurs in 1995 when Lum visits Chen Zhen, an artist from China living in Paris. Lum, then teaching at L’École des Beaux-Arts, is introduced to a group of Chinese artists and curators that had immigrated to France after the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and crackdowns. Lum observes Chen’s “sense of dislocated habitation” in his artwork — particularly Maison Portable (2000), a wood sculpture that reads simultaneously as a cradle, cage, wagon, playpen, Chinese sedan, and prison. Reflecting on the work, Chen describes how “[t]he house can be a utopian space, virtual, immaterial, spiritual, a space ‘between.’”¹⁵ This concept of “homelessness” allows him to circumvent contemporary art world expectations to represent a particular ethnic community or nation. Chen also drew inspiration from Daoist philosophies, particularly Lao Tzu’s invocation to “abandon knowledge and discard self ” in order to live beyond social convention, in fluidity with the Dao 道 / The Way.¹⁶ Regardless of ideological or physiological container, home becomes both nowhere and everywhere — a consciousness always with oneself. Conversing with Chen, Lum seems to find a peace and affinity, inhabiting the ontologies undergirding Chen’s views of life, art, health, and spirituality, and feeling all in holistic relation. “During a period of disillusionment for me, he reminded me of the need to always form and express new connections in one’s art, especially in terms of the ways in which one inhabits the world.”¹⁷

The third moment is in 2005, when Lum is in Delhi for a conference and takes a bicycle-cab ride to Chawri Bazar in Chandi Chowk, a bustling 17th-century market considered to be the soul of the city. In a striking passage, Lum describes this phantasmagoric, hallucinatory, and immersive sensory experience — a collision of diverse populations and offerings filling a maze of narrow lanes and brightly-coloured posters:

Interspersed throughout are countless eateries engulfed in steam and filling the air with a plethora of smells. Barking voices from megaphones clash with music from loudspeakers. There are mosques, Hindu and Sikh temples, and Catholic and Protestant churches all in close proximity to one another …Teams of long-limbed, yellow-brown monkeys darted from the shoulders of one person to the next, their sudden appearance surprising no one but me.¹⁸

Marveling at this cacophony of life, Lum asks himself: “How can art compete with what I have just experienced? How can art even come close to all that I have seen, smelled, touched and heard here? I realized that art cannot compete. Life is infinitely more complex . . . And yet art should be about life, and draw from it sustenance and relevance.”¹⁹ In this moment, Lum is an open receptor, immediately at home in this state of mind, accepting and surrendering to everything around him in fluid recognition of the currents between self and universe. “Everything is relevant,” he so inclusively writes. Art’s modest role is simply to evoke this.

■

¹ Email exchange with Ken Lum, April 2021. See also Dorothy Woodend, “Ken Lum, an Artist Double Crossed?” The Tyee, February 11, 2020. https://thetyee.ca/Culture/2020/02/11/Artist-Ken-Lum-Is-True-Child-Of-Vancouver/.

² Ken Lum, Everything is Relevant (Montréal: Concordia University Press, 2020), xxv.

³ Lum, “Seven Moments in the Life of a Chinese Canadian Artist,” 20-22. Originally published in Hou Hanru and Hans-Ulrich Obrist eds., Cities on the Move (Vienna: Verlag Gerd Hatje, 1997).

⁴ Lum, “Dak’Art 98, The Dakar Biennale,” 32. Originally published in Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art 9 (Fall/Winter 1999), Duke University Press.

⁵ Lum, “On Board The Raft of the Medusa,” 36. Originally published in Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art 10 (Spring/Summer 1999), Duke University Press. For these pieces, Lum undertook extensive research at the archives in D’akar.

⁶ Lum, 36.

⁷ Lum, 41.

⁸ Lum, “Inaugural Editorial,” 97. Originally published in Yishu: Journal for Contemporary Chinese Art (1:1), 2002.

⁹ Lum, “Surprising Sharjah,” 125 and 129. Originally published in Canadian Art 22:3 (Fall 2005).

¹⁰ Lum, “Unfolding Identities,” 140. Originally published in Kamal Boullata ed. Sharjah Biennial 7: Belonging (Sharjah: Sharjah Art Foundation, 2005).

¹¹ Lum, “Unfolding Identities,” 143.

¹² Lum, “Something’s Missing,” 158-159. Originally published in Canadian Art 23:4 (Winter 2006).

¹³ Lum, “Homes,” 9. Originally published in Viennese Story, curated by Jérôme Sans (Vienna: Wiener Secession, 1993).

¹⁴ There is no place like home was originally intended to be a modest poster project. In response to its attempted censorship by conservative factions of Vienna’s city government, the organizers, Museum in Progress, with the Vienna Kunsthalle, the Canadian Embassy, and several human rights groups, banded together to expand the work into a large-scale public project. For a detailed account of events and analysis of this work, see Grant Arnold, “Ken Lum: The Subject in Question,” in Ken Lum (Vancouver Art Gallery and D&M Publishers Inc., 2011), 35.

¹⁵ Lum, “Encountering Chen Zhen: A Paris Portal,” 166. Lum quotes Chen Zhen from Chen Zhen: Invocation of Washing Fire (Gli Ori: Prato, 2003), 190.

¹⁶ In the Tao Te Ching, the Dao is described as the natural order of the universe whose essence humans can intuit and find harmony with, realizing the interconnectedness of all life everywhere. See Moss Robert trans., Laozi: Dao De Jing (Oakland: University of California Press, 2019).

¹⁷ Lum, “Encountering Chen Zhen,” 175.

¹⁸ Ken Lum, “Something’s Missing,” 163. Originally published in Canadian Art 23:4 (Winter 2006).

¹⁹ Lum, 163.

“A Consciousness of Belonging: On Ken Lum’s Everything is Relevant” by Joni Low was featured in Issue 3.44 (Summer 2021). Order a single copy of the issue or subscribe today to receive this issue plus two more.