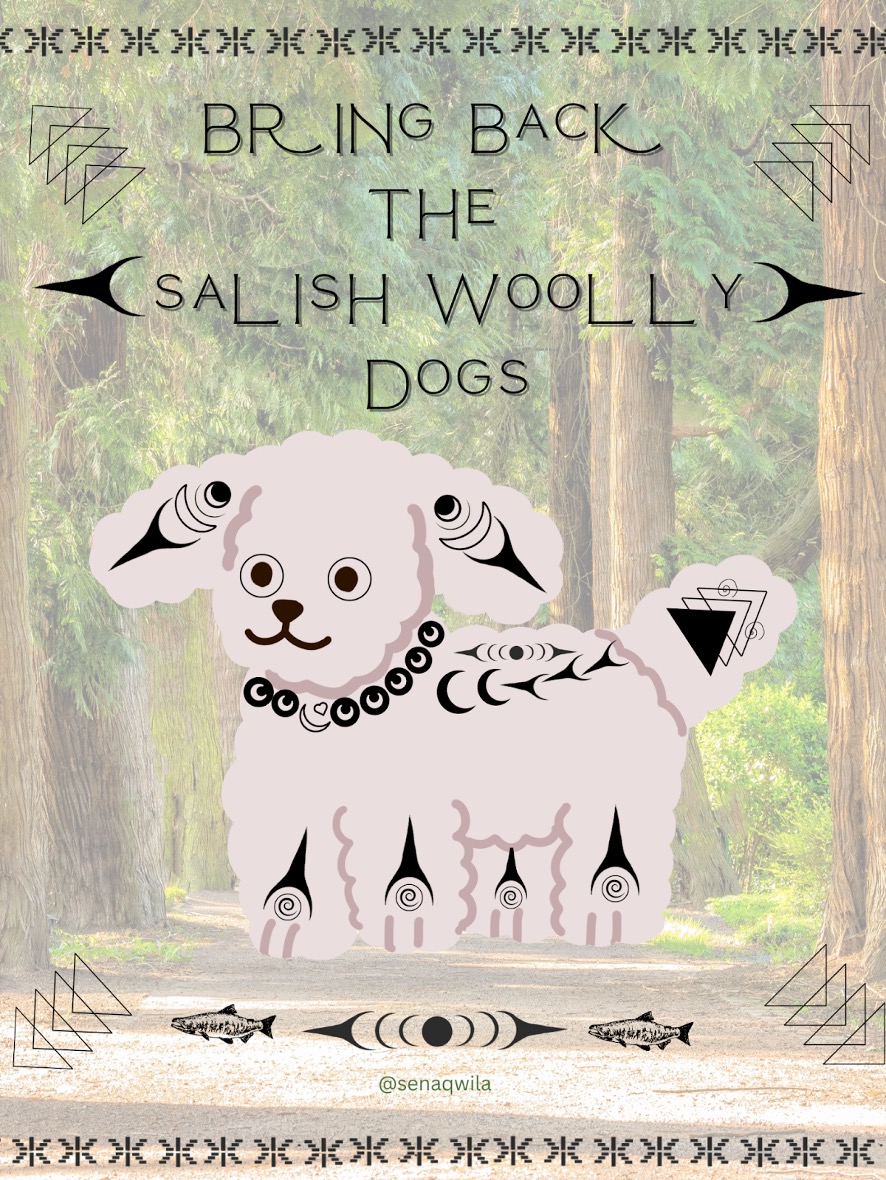

I began to know the deeply meaningful work of Senaqwila Wyss from her Salish Woolly Dog memes. These brilliant interventions into the biased and erroneous colonial narratives about the wool dog made by Senaqwila do the important work of bringing forward Salish ways of knowing and being. Senaqwila Wyss is an artist, author, ethnobotanist, cultural programmer, and language teacher and learner. As we think about Indigenous land and Indigenous languages and the connection between the two for this series, I felt it important to include the perspective of someone who advocates for our non-human relatives and their relationship to place.

— Susan Blight

Sx̱aaltxw, the late Louis Miranda, Elder from the Squamish Nation, was interviewed in the 1970s at a time when B.C. First Nations were at a critical point of collecting written and spoken interviews, as well as creating audio recordings of the languages.1 This series contains an archival document of all known animals, plants, and villages. While the section on animals is sparse, what it does say has changed a big aspect of how I read anthropological documents on the Salish Woolly Dogs.

In my community’s Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Sníchim, or Squamish language, we call the Salish Woolly dogs Pa7pa7í7ḵin, meaning “fluffy-hide dog.” Not only were they companions and pets, but they were also among the first ones we would think to save in an emergency. Miranda describes our relationship with the Pa7pa7í7ḵin in his interview: “If anything went wrong, a woman would grab her dog and then her child.”2

This quote has changed my life and perspective on the Salish Woolly Dogs forever. Imagine a house fire, a flood, or any emergency that forces you to run out the door with nothing but the lives of you and your loved ones—that is what comes to mind when I think of Miranda’s words, especially as a Squamish Nation language learner, mother, fur-baby parent, and weaver.

Archival records written by settlers, colonizers, and anthropologists fail to capture the true essence of the relationship we have as Salish Nations, as Stelmexw, as Indigenous peoples, to our beloved—and now extinct—Salish Woolly Dog.

***

The timeline of the Salish Woolly Dog’s extinction aligns with many events that impacted our Coast Salish lands and waters, particularly from the late 1800s through to the early 1900s.

Some dates:

1827 – Hudson’s Bay Company established Fort Langley, BC

1859 – Salish Woolly Dog named “Mutton” is killed and turned into a hide 3

1867 – Section 91(24) of the Constitution Act assigns the federal government authority over “Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians”

1876 – Indian Act

1885 – Potlatch Ban

1922/1935 – Woolly Dog photographed in Victoria, BC 4

These are some of the major events that give an idea of what Salish communities were dealing with at the time, facing ongoing oppression and threats, being forcefully removed from land through the sale and privatization of our lands and waters, being called “property,” being confined into reservations, and so on. During this time, Salish peoples also witnessed the widespread slaughter of bison, impacting Indigenous communities on the plains and the culling of sled and arctic dogs that damaged the transportation systems of arctic Indigenous communities.

Colonial changes forced our people into wage work, made fishing forbidden, prevented us from feeding our families and Woolly Dogs with salmon, created damaging canneries that cleared our waterways and opened the fur trade. Rather than continue to weave our own blankets, we were forced to purchase them.

The furs of the Salish Woolly Dog and Mountain Goats were highly valued by our peoples and required intensive care, knowledge, and skill to work with. As we did not have sheeps’ wool or the synthetics that are used today, Coast Salish weavings included Woolly Dog and Mountain Goat hair/fur, along with plant materials. These plants include fireweed fluff fibers, stinging nettle stock fibers, and red and yellow cedar bark. Salish weavings are intricate and have a variety of seasonal designs that are made to be adaptable and specific to the coastal rainforest that we are accustomed to as Coast Salish People. The Woolly Dog hair is much better for insulation and warmth than other comparable wools, and the cedar bark weavings would also provide weather-proof, waterproof, and woven tight weavings to protect from the elements.5

The Hudson’s Bay Company, in cooperation with Federal Indian Agents enforcing the Indian Act, was instrumental in the downfall of this beloved creature, discouraging our relationship to weaving and to caring for our Woolly Dogs.

***

As I raise three daughters with my husband alongside our pack of huskies, my dream is for us to continue to see and experience the importance of dogs in our family. Our companionship and training relationship with them brings us much closer to seeing the return of the Salish Woolly Dogs!

***

Further Reading/Listening

“Deep Dive into the Salish Woolly Dogs with Senaqwila Wyss” | Live It Earth

“Senaqwila Wyss on the Salish Woolly Dogs” | MONOVA (Museum and Archives of North Vancouver)

Salish Woolly Dog Memes by Senaqwila Wyss

- Randy Bouchard and Dorothy I.D. Kennedy, “MS 7245 Knowledge and Usage of Land Mammals, Birds, Insects, Reptiles, and Amphibians by the Squamish Indian People of British Columbia,” British Columbia Indian Language Project, 1976, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- See Cathy Koos, “Mutton: The Wooly Dog of the First Nation,” Conference of Northern California Handweavers and Meghan Bartels, “Lost ‘Wolly Dog’ Genetics Highlight Indigenous Science,” Scientific American, December 18, 2023. ↩︎

- An archival photograph circa 1922 shows a woman named Ruth Sehome Shelton, siastənu, working in a cemetery with her dog, which may be a Woolly Dog breed (Wayne W. Williams (Tulalip) collection). In another photograph from 1935, a Salish Woolly Dog is pictured on the East Saanich reserve, about 20 kilometres north of Victoria (W̱SÁNEĆ Nation / University of Victoria Libraries Special Collections). See the article “Rare blankets made from fur of extinct woolly dog on display at North Vancouver Museum,” CBC News, May 14, 2023. ↩︎

- For more information, please see Patricia Jollie, “A Woolly Tale: Salish Weavers Once Raised a Now-Extinct Dog for its Hair,” American Indian 21, no. 4, Winter 2020. ↩︎