This piece originally appeared in Issue 3.38 (Spring 2019).

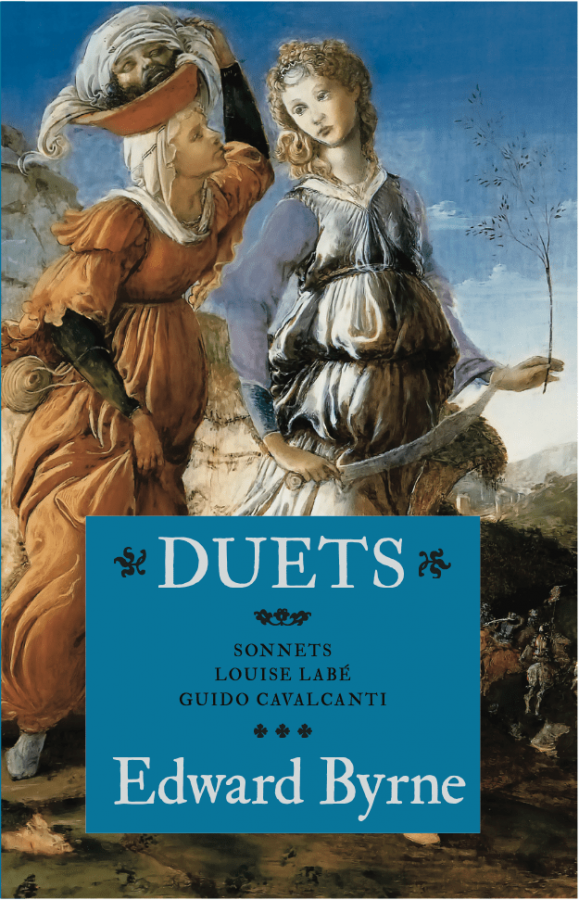

That such a gem is Ted Byrne’s creation is hardly surprising. Byrne is a Vancouver- based poet-scholar who has dedicated himself to the study of the work of Henri Meschonnic on poetics and translation theory for a long time, and the traces of his long commitment to this study are well visible. Duets is a translation from French and Italian of sonnets by Louise Labé and Guido Cavalcanti, poets at the centre of the poetic scene of their respective times — early modern Lyon and late medieval Florence. But the appellative “translation” reveals all the complexities of this work and the complexity of thinking about the translation of poetry itself. At stake here is not the time-old Latin-derived saying traduttore traditore (the translator is both a betrayer and the one who carries you across linguistic geographies or world borders). That much we know and we also know that this is at stake in every translation of poetry. But in the spirit of Meschonnic’s theorization of poetry and translation, Byrne takes up the task of translating “ethically.” A poem is an ethical act. A translation is also an ethical act. It is not the translation of fixed-form poems because the poems that Byrne translates are already transformations of “forms of life” and producers of subjectivity. The true betrayal of Labé and Cavalcanti would be the reading of Byrne’s work in order to find identity, equivalence, or communication, that is, meaning rather than rhythm and sense of language: “If to translate a poem we translate form, we are not translating a poem, but a representation of poetry, linguistically and poetically false.”1

Louise Labé’s poems are the focus of the first four sections of Byrne’s book. In the first section, “Sonnets: Louise Labé,” her sonnets (two quatrains and two tercets) are translated into nine-line poems of different forms (primarily 3+3+3 or 2+2+2+3), a poetic of constraint of sorts. But the translator-poet also intervenes into the form of the poetic series with translational reflections on the spirit of Labé’s poetry: two unnumbered sonnets are added to sonnet 6 and 11, taking up the potentiality of reading Labé’s writing “as” theory of language through the eyes of Michel Foucault and Julia Kristeva. This is also an appropriate move to illuminate Labé’s strikingly feminist poetics. The second section, “The Rilke Versions,” based on Rainer Maria Rilke’s translation of Labé, questions the stance of “augmentation” and “diminishment” of the act of translation. Reading this section alongside the first (both sections are based on the same originals) places translation in the realm of possibilities rather than comparisons of value or equivalence: it is a field of correspondences that does not reduce the infinite to a totality (the “better” work) and opens up possibilities of subjectivities in the reading of the poem. This concern is even more evident in the collaboration section with Kim Minkus, “from 19/19,” revolving around Labé’s sonnet 19 on Diane and Actaeon, as well as in “Pendant,” the following fourth section.

Attempting to fix Byrne’s work within the confines of a genre (or a trade) would be futile. These poems are simultaneously translations, recreations, transcreations, research acts, or conversations with the “original” poets (Labé and Cavalcanti) but also with the many poets with whom they were in dialogue in their own time (Olivier de Magny, Maurice Scève, or Dante Alighieri) as well as the poet-readers who have in turn translated them throughout centuries. The translation of Cavalcanti’s sonnets in the final section of the book, “Sonnets: Cavalcanti,” speaks to Ezra Pound’s own translations. A close reader of the modernist poet, Byrne was consciously or unconsciously influenced by Pound’s poetics of translation. Not only did Pound establish the text of Cavalcanti that Byrne used for these translations, but Byrne’s very early translations of Cavalcanti were written in the 1970s in the margins of Pound’s own translations, thus forging a dialogue, echo, and literary exercise. We may wonder about this double layer — translating the original alongside another’s translation — but only in order to realize that reading and writing do always pass through the language of the Other (Lacan is yet another interlocutor with Byrne’s translations). Pound’s language, then, enters Byrne’s work yet it refuses subservience. So does the translator’s work to either original and to Pound. e poet-translator intervenes in the powerful discourse of Love with remarks about language use, style, and grammar that illuminate the spirit of Cavalcanti’s philosophy. If the translator is the one who traverses world borders, we may then ask, how many worlds are being “carried across” in Byrne’s text?

It is only appropriate that the poets who created and rearticulated a discourse of Love (eros, carnality, vision, speech, as well as the philosophical space of poetic love) are translated into a language that asks the reader to bring the body and sensorial faculties to the experience of listening — movement, rhythm, syntax, and prosody. The act of love does not reside in the idea (the eidos) of poetry but in the bodily texture of poetry itself. Unwriting writing — that is, the illusion of the representation of language — Byrne’s translations are a poetic gift asking the reader to consider how the translation of poetry can only be faithful to one command: transform our thinking of language.

- Meschonnic, Henri. Ethics and Politics of Translating. Trans. Pier-Pascale Boulanger. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2007.