From Issue 4.1: Anti-Monuments (Fall 2023)

Wayde Compton

My first question is about what it was like being in Montréal during the 1969 Sir George Williams Affair.1 Were you there at the time?

Hope Anderson

Well, I wasn’t a student. I’d just turned seventeen when that happened. I was taking some evening classes at the university and planning to go full time in the fall. I wasn’t very political at the time, just becoming acquainted with the political world and trying to get an understanding of it. There had been a conference of Black writers, I think if my memory serves me right, at McGill. I’d gotten to one session with Walter Rodney as the speaker and it got me more interested in politics, but I was still very young and didn’t have a wide enough view. Ironically, though, one of the reasons why I got interested in literature was because of cricket. I’m a fan of the game cricket, and when I was younger, I was a pretty good player. That summer I read C.L.R. James’ book, Beyond a Boundary, because of the fact that there’s a Caribbean guy who writes and is well-respected. It piqued my interest a little bit. From the conference, I became acquainted with Anne Cools, who later on

became the first Black senator in Canada. She was sort of a mentor of mine.

But that happened a couple years later, after the actual…insurrection. That word has currency, right? So, they called it a riot. The students called it a rebellion. So, I wasn’t actually there for the event, but it obviously affected a whole generation of Black students there and it radicalized a lot of people. Coming to the defense of the students, people who were apolitical suddenly became political because of obvious injustice and the blatant racism that most people didn’t think or acknowledge as part of the Canadian experience became front and centre. A real thing. So, yes, to answer your question, I wasn’t there, but I was in the city, affected by the developing situation as it unfolded. And out of that, as I mentioned, I became friendly with Anne Cools. I know for sure there were two people who were convicted and who served prison terms: herself and Rosie Douglas. Rosie Douglas later became the Prime Minister of Dominica. He died prematurely, after only being in office for a few months.

They gathered a lot of the younger people of my generation, because they were probably eight or nine years older than I was. So, there were a lot of young people who sort of ended up going toDawson College, because we boycotted Sir George.

When I was there, there were eighteen Black students. I remember that specifically [laughs]. There were eighteen of us.

WC

Eighteen. Wow.

HA

Out of a student population of 1,800. We had a – We didn’t call it a political club, but we had a cultural club. I was kind of instrumental in getting it started, and by then I had started writing poetry, so it was mostly a cultural effort. But out of our

eighteen students, sixteen were full-time members of our club. We had 98% participation, just because of the whole political atmosphere of the city. I became a mentor for our group. Just after about a year of being at Dawson, I got married and we had a house a few blocks away from the college which was sort of a communal house. A lot of the students hung out at my place. Anne was ever-present there and we had study groups and all that kind of stuff, which she led. She introduced me to to the work of several Caribbean writers, including Austin Clarke.

He had just published what is still one of my favourite books, When He Was Free and Young and He Used To Wear Silks. He was at House of Anansi with Margaret Atwood. He’s one of the founding writers there. For that acquaintance, Anne was instrumental in me meeting him and arranging for me to send him a very sophomore manuscript. The curious thing about that was that they didn’t reject it out of hand. I got some encouragement from House of Anansi. They didn’t publish the manuscript, but I did get some encouragement from them to keep going.

I should say that my early literary interests were shaped by a very great friendship with Michael Harris who taught poetry at Dawson, by my friendships with Guy Birchard and with Claudia Lapp who was one of the founders of Véhicule

Press, and by the Véhicule readings.

But, yes, the Sir George Williams affair was very pivotal in my overall beginnings of understanding the African presence in Canada and being re-educated from an orientation that was essentially a colonial understanding of, and appreciation of, culture and history. Malcolm X stated that as people of African descent, we are not a minority. We are part of a multicultural world.

One of the major themes around our experience at the time in around 1969-1970 was what we called the “third-world” focus. As a matter of fact, at Dawson, we created what we called the Black and Third-World Club. We also instituted a Black and Third-World Office at the college. I don’t know if it still exists, but it’s one of the things that we did. As a matter of fact, I think even when my daughter ended up going to Dawson years later it still existed – maybe 20 years after.

WC

Wow.

HA

I don’t know if it’s still functional, but it was still there.

WC

So, this is really interesting. I know your writing mostly in the context of BC, but that’s because that’s been the area of my study. So how do you get from there to BC?

HA

Well, it’s a confluence of things and it’s centred around my friendship with Anne Cools. In 1972–73, I was at Sir George. Once the ban was lifted, I went there for a year and a half and was actively trying to finish an undergraduate degree. But I had a young family, and so I was trying to figure out my life. Anne had moved to Toronto. She was being subtly recruited by Pierre Trudeau to join the Liberal Party, even though she was a political radical. It was one of those things that remains a mystery to me how that happened [laughs]. She was a radical socialist and somehow Trudeau was able to charm her, or whatever he did, to consider running for office in Toronto.

So, being one of her protégés, she told me I should consider moving Toronto as well. So, I left Sir George thinking that maybe I would move to Toronto. I had gone to Toronto when Anne was the headline speaker at a massive rally in support of Walter Rodney when he was being ousted from the University of the West Indies. There was a massive rally in Toronto, and it was my first big public reading. I read there and the reading was really well received. So, when she suggested a move, I thought, well, I’m not really tied to Québec even though there are so many complex issues around Québec. I’ll tell you a little part of it. Okay. That house I mentioned – that house which was kind of our hub for political activity – even though I was at Sir George, I was still emotionally tied to Dawson because we’d started the first year the college was established, and we had opened up the admission process to include a special admissions program for Black students.

So, because of our open admissions policy, we went from our 18 students to maybe 70, 80 students when I left there in ’72. So, I was still very much involved in what was going on there.

And, as I said, we had established the Black and Third-World Department, and had a Black Studies program, a lot of those new students also were part of our group that met at my house, as it was only a couple of blocks away from the college. But there was tension in the Black community because the Black community had grown tremendously – I mean, exponentially. And since 1966 to 1973, I’d have to go and look back at the at growth. But we’d had an insular, small community in a little district called Little Burgundy, which was where most of the Black people were concentrated, where we had the Negro Community Centre. I was put on the board of the Negro Community Centre even though I was nineteen, twenty years old. We had a newspaper. But Black community grew in the Côte-des-Neiges community, and so there was some tension between both groups. It’s just the way of political activity, that very quickly divisions become evident instead of unity. Their political lines begin to be drawn. There are people who are Black nationalists. There are people who are pan-Africanists. There are people who are socialists. There are people who are Marxist- Leninists. And so a lot of that conversation was happening in our house. Even though at the time Anne was a social democrat and my political leanings were essentially led by my understanding of her historical analysis. She was very stridently anti-Black-nationalism, right? But there were certain people who were nationalists.

Anyways, one of the main things that made me make a decision about leaving Montréal was this one particular event that transpired. A group of people attacked our house.

WC

Oh, wow.

HA

I had a young child – my daughter was only two years old – so I had to make a decision about whether I wanted to stay in that kind of environment, because I was never politically violent. When the situation took that turn, I had to start thinking about what I wanted to do. So, that began my journey to the West Coast because I went to Toronto and I really didn’t feel comfortable there because, even though Anne and I were friends, I wanted to chart my own course.

I’d met the poet Gerry Gilbert. He’d come to Montréal to visit. And I’d met George Bowering, who had taught a class at Sir George. Gerry in particular had said, “If you ever come out west, you can come and visit with me.” I remembered that. So, in the middle of the winter, I just got on the train and headed west, not sure what I was going to do when I got out there [laughs] because I had to figure out how to get my then wife and my daughter out. By then I began reading more and became more acquainted with the West Coast poetry scene. I liked what was happening. I liked what I’d read from TISH magazine, and The Cap Review was just established and I’d read the first issue, and I also became acquainted with the Black Mountain school of writers, since I became acquainted with the fact that there had been a conference in Vancouver that featured Robert Duncan and some of those poets. I thought it was just a very exciting scene then. When I got to BC, I found the writing community to be very active and welcoming. So, that’s how that began.

WC

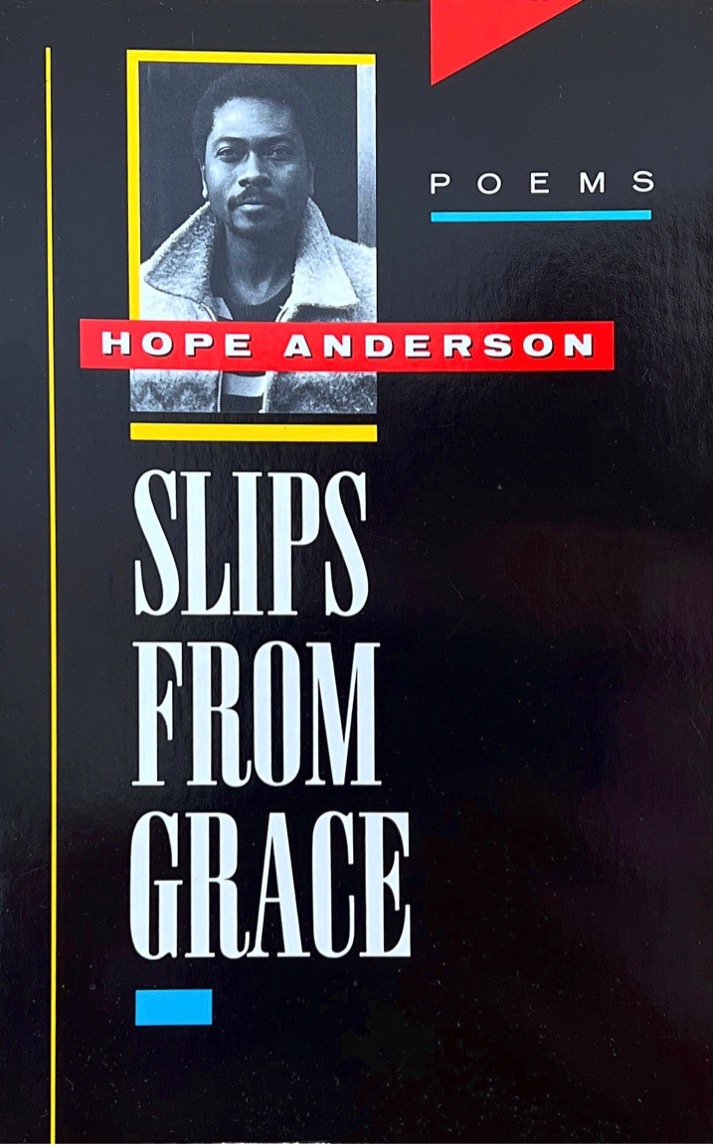

Well, that’s interesting. Something about your Coach House book Slips from Grace that’s very interesting to me is that you’ve got so many poems in there dedicated to all these different BC writers. It gives us a sense of the scene and which poets you’re in communication with and speaking to. The book itself presents this overview of the kind of communal nature of poetry here. When did you start writing the poems that ended up being in Slips from Grace?

HA

In 1979, we put together the anthology called The Body,2 and we had a lot of hope for establishing a publishing house – myself, and David Phillips, and Pierre Coupey – because we were neighbours. Being young and inexperienced about the ways

of the world, I was still, when it came to just how to handle life… To be honest, and that’s part of my appreciation of Barry Nichol, because we would have those kinds of conversations. Up all night drinking coffee and talking with him, a most brilliant and generous mind he had. I was working at the UBC Bookstore and, on a whim, I quit my job. It doesn’t make sense now at all, but at the moment I did it, it seemed like what I wanted to do. But it put my whole life at risk. It was one of the first times I risked my life because I thought I wanted to be a poet full time [laughs], and because we were so deeply committed, you know? From the conversation that happened with David, we were excited about the possibilities and all of that

stuff. But we were foolish.

So, I ended up, as an aside – well, it’s not an aside. It’s really intrinsic to a response to your question. When I was a young boy, mid-teens – I moved to Canada when I was sixteen – one of my best friends from Kingston College, my high school in Jamaica, ended up being Bob Marley’s road manager. We were friends at school and when Bob came to Vancouver in 1978, my friend Neville Garrick, who did all the designs for his album covers and did all the set design – he’s a really fine visual artist – he came by our house and we hung out together on Tatlow Avenue. As a matter of fact, I did Bob’s introduction to the audience at the Queen Elizabeth auditorium.

So, in 1979, when things went awry on Tatlow, I decided to go to Jamaica because I hadn’t been there for twelve or thirteen years. I hadn’t been back since I was a teenager. I went because another friend of mine was in the Jamaican government. As a matter of fact, he went to the University of Toronto and he was at that event where I’d read my poems, and he was encouraging me to think about and participate in Jamaican politics. So, I went. Again, my usual enthusiasm and wholehearted kind of passion for these things. While there I made a film of Bob Marley’s studio, I interviewed Peter Tosh, Rita Marley, the Marley children’s group The Melody Makers, and other Jamaican musicians. An excerpt of the film was shown to George Stanley’s class in Terrace when I went to read there in 1988. I would like to note that this film was subsequently stolen from me and I will be making every effort to retrieve it.

I went to Jamaica, and I began writing those poems while I was in Jamaica and on my way back. When I came back to Vancouver, I lost a whole bunch of them because, as a matter of fact, I wanted to present the entire manuscript as a musical because of the strong musical influence of the Caribbean that kind of seeped in during my good six or nine months in Jamaica.

So, I lost a lot of those poems. I didn’t do much with the remainder, but I did share a couple with George Stanley. The “1980” poem was one of the few poems I’d shared publicly because I felt the urgency of it and its value at the time. When I wrote that, George Stanley decided in 1981 to write a response to it, and then we began the series. So, to answer the question, I began writing in 1979.

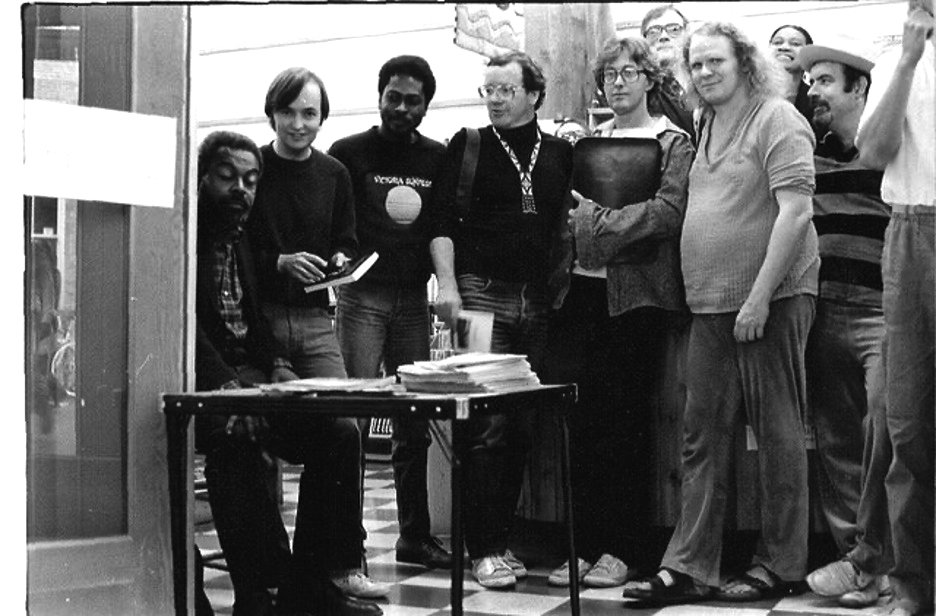

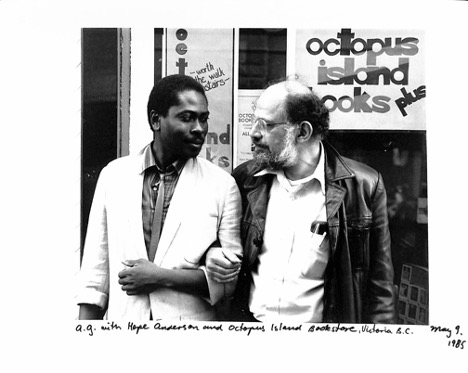

By the early 1980s I’d moved to Victoria to a job at Munro’s Books and I subsequently started Octopus Island Books. In 1984 I organized the Victoria Sunfest, one of the first festivals in the city, if not the first. The Sunfest started with Margaret Atwood in July 1984 and ended with Irving Layton in September of that year. The main program in August featured Amiri Baraka, George Bowering, George Stanley, David Phillips, John Pass, Doug Beardsley and bpNichol and as always, much music including one of my all time favourites roots musicians, Taj Mahal. Octopus Island Books continued literary events that featured Al Purdy and culminated with hosting Allen Ginsberg in 1985 before I had to close its doors.

After the August Sunfest readings we were just sort of hanging out at Octopus Island Books, all the poets that I invited read, but I didn’t read. So, bp asked me to read. He said, you know, “You didn’t read at the reading. Read something for us!” So, I read, and after the reading he said, “Hope, you got to get these things published.” So, for the next couple of years, I just focused on the poems in the manuscript and ended up publishing it with Coach House in ’87.

WC

So, here’s a question. One of the epigraphs in Slips from Grace is from Smokey Robinson’s “Tracks of my Tears.” It’s interesting because it’s this wistful sentiment kind of like, “I’m the life of the party, but deep inside I’m blue.” It expresses this sense of – in my mind anyway – this social scene that you’re describing, this very robust kind of cultural scene, but then also this personal sense of reserve. I wonder, for you, is that expressive of what it was like for you as part of that scene? I’ll add that, in my own experience, as a poet coming up in Vancouver in the ‘90s who was the only poet of African descent in my scene, I was often writing using allusions or forms, and reading books that my friends weren’t reading and didn’t necessarily know about. So in a certain way, yes, it was a scene, but in another way, I was also doing my own thing. It felt like having conversations with books rather than the people who were there. I wonder if that was true for you back then.

HA

Very, very profoundly. When W. E. B. Du Bois talks about double consciousness, which is the experience of every conscious person of colour, it’s a need to explore aspects of yourself that the rest of this society is unaware of, deliberately or unwittingly. For example, my former wife and I, we used to have events at our house because I was always trying to get people to understand that, you know, Black people have something special to offer to society. That’s another conversation. But my friends, who were essentially literary friends, we would, at our house – I had a whole range of music. I had a whole range of things that I would listen to. But my very good friends, I would be introducing them to Black music, right? But at the same time, I’m listening to everything they’re listening to on the radio, on FM, right? So, I’m acquainted with the popular culture by osmosis. But what I embrace and what expresses my innermost or deepest thoughts and feelings are extraneous to some of those experiences.

Someone said recently, “Hope never seemed to deal much with his Black experience,” which is so far from the truth.

WC

That’s not true. It’s all through Slips from Grace, all these different allusions to Black culture, Black writers, Black music. It’s all through that book.

HA

Right. But I guess what they were referring to maybe in our conversation – I don’t know. I’ve never excluded it but, as you said, being the only Black person in a world that was essentially, you know, white Canadian. . . To take that on, it’d be a full-time educational role. It’s not that I compartmentalized in my life, but there were just certain things that were not proscribed, but not part of the current conversation unless I made the effort, right? I’m sure that probably was in some ways your experience, too.

One of my early influences was Leroi Jones before he became Amiri Baraka, and so I understood what it meant to be a Black poet in a white milieu. I understood that through my knowledge of how he tried to navigate and chart a way for himself as a writer. His way of being before the Black cultural movement was perhaps the only real way for a Black writer in Canada, I felt, because our community in Canada is so small. To chart any other course, you would remain invisible. Your anthology Bluesprint3 demonstrates that fact: that there are all kinds of writers. There are all kinds of Black people writing, but we never hear a thing about them – unless you’re digging for it. My presence, for whatever it’s worth, was charting a way with the culture, but never at any point denying the power of the historical Black experience. So, the manuscript I’m working on now that’s giving me the most trouble is a manuscript called “The Grace of Centuries.” I’ll probably send parts of it to you sometime. If you’re interested.

WC

Yeah.

HA

Remind my daughter how I got started on that project. When I had the cafe in town here called The Well, a woman says to me she does not understand how a Black person could be a Christian. It not only raised my ire, but it made me want to speak on that subject because – [pause] A lot of reasons. The fact that people make certain assumptions and are confident that they’re speaking truth without any knowledge about the African presence at all. What I’m trying to get at is that no matter what it is that I’m writing, it’s being told from the point of view of a Black person of colour in whatever the circumstances. I may not say it in broad strokes, but if anybody’s reading with any amount of intelligence, they’ll see it. They’ll know. It’s not incumbent upon me to speak for every Black person, but I’m one Black person speaking, and it colours everything because it’s an essential part of my experience. I’m not sure if that’s the question you’re asking, but that’s the question I’m answering.

WC

So, you were away for twenty years in Florida, and then you came back in 2010, and now you’re writing again. Is there something about Canada or BC that inspires you to write? [Hope laughs] Is this the place that brings the poetry out in you? And

what are you working on?

HA

My journey to Florida was transformational because when Slips from Grace was published, I was not working, and I was hoping to find a job. I don’t know if it’s providence or serendipity. I went to Florida – my parents had just retired there – and I was visiting with my parents. My mother decided to speak to me very directly, saying, “You know your marriage is over. This poetry thing is not working out for you. Why don’t you try to get a job in Florida?” And I said, “Well, you know, it’d be difficult, there are a lot of complicated issues.” But I said, “Okay, to satisfy you I’ll apply for a job.” I looked in the phone directory. I said, I’d love to work at a Black college and there was only one in South Florida. There was Florida Memorial College and there was Bethune-Cookman College up the coast a little way.

I went to Florida Memorial and took my copy of Slips from Grace to the Academic Dean there. My mother said to me, “Hope, you’re going get a job right here.” I said, “Oh, you know…” She said, “I’m going to be praying for you to get that job because you need to be here.” This happened on Friday. I had no status in the States at all, Wayde. I had no status. The Monday morning, I get a call. The Dean wants to see me. Just like you and I are talking, we have this conversation about all kinds of stuff, and he said, “We’ve got to get you situated here, get you a job here.”

But I explained to him that the book was published, I had six readings lined up. I’d made commitments to do those readings. So, I explained to him, “All right, I got to go back to Canada because I had one reading in Toronto, one at the Vancouver Art Gallery, and a couple more.” As a matter of fact, one in Prince Rupert. I almost stayed in Prince Rupert because I thought I could get a job there. But I had made a commitment to my mother, and Florida Memorial had offered me a position. They were working out my status, and it was going to take three months for my status to be confirmed. They were doing everything to get me my work permit. So, I got the work permit, and I ostensibly was hired as a poet-in-residence for three months. While I was doing that, they looked at my resume and saw that I managed bookstores. They didn’t have one, so they asked me to start one.

That became my passion because it was a small college. The year that I was there, the college was going through their accreditation process. They wanted to do a lot of things to change the trajectory of the college. They were looking towards becoming a university. The then-President of the college and I became acquainted, and we bonded, and the Vice-President and I bonded, and we went on a ten-year redevelopment of the college. So, it required a lot of my attention. While I was there, though, I did start an academic review. We were hoping for it to become a peer-reviewed magazine, but it never happened because I took on so many other responsibilities for the university. It ended up being a very wonderful experience because it utilized a lot of the skills that I’ve acquired over the years outside of writing. I like promoting other people’s stuff, and I have an entrepreneurial bent as well. They gave me the responsibility of being the director of their – in Canada, we call it “ancillary services” and in the States, they call it “auxiliary services.” Primarily it started with the bookstore, but I just kept adding services that would generate funds for the university outside of their regular budget.

That was very challenging, but very rewarding. And I began singing, which is my primary, you know, my primary passion.

WC

Did you come back to Canada when you retired? Is that why?

HA

Well, what happened was my youngest daughter, who I mentioned to you found me through Bluesprint, when we got connected, I always said, I love BC, and she always said, “Dad, when you get to a certain age, why don’t you think about coming back?” Certain things transpired in my life that made it possible, so I came back to Victoria in 2010. When I opened my arts cafe, The Well, George Elliott Clarke attended the opening which featured Derek Walcott as our special guest. I wanted to have a cultural space, but with a spiritual component to it [laughs], because I just felt that my friends who are writers are missing a dimension. Part of the Black experience is, I’ve discovered, that Black people are very spiritual people for historical reasons. It means that we don’t get blown away by trouble. We don’t get off track by challenges. This is just my sense having lived for those twenty years in that kind of environment. The evangelical world is really foreign to the Black church. We are a church; we are a people who stand our ground. We fight in the church, right?

WC

The church is the centre of the activism, and culture, and music – so many things.

HA

Everything emanates out of the church. So, to the things that I’m writing now: I’m working on two major long poems, one called “The Grace of Centuries,” which is dedicated to the memory of Phyllis Wheatley, and then, “In Pursuit of Hope,” which began out of a conversation I had with bpNichol in 1984, and then again in 1987. Kind of a dual autobiographical story – a meditation on the personal and the need for spiritual anchoring. Because Slips from Grace was essentially about being unmoored. “The Grace of Centuries” is being anchored. It’s the African presence not only in Christianity but in the religious text. The African presence and the value of the religious experience to people of African descent, and the historical reasons why we’ve been excluded from the conversation around religious texts, right? So those are the two major poems I’m working on.

While I’m working on those, whenever I get stuck – because, for me, they’re very challenging endeavours – I’m writing some other poems that I called “Family Chronicles from Mufn Land” and that’s another series of poems. Those ones I think are done.

- “The Sir George Williams Affair began in the spring of 1968 when several Caribbean students fled a complaint to the university administration charging that a science professor was either deliberately failing them or awarding them low grades. When the administration failed to take action, the complainants…rallied other students on campus as well as members of the Black community; and a group of protesters eventually occupied the university’s nerve centre, the computer room.” David Austin, Fear of a Black Nation: Race, Sex, and Security in 1960s Montréal (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2013), 26. ↩︎

- The Body, edited by David Phillips & Hope Anderson (North Vancouver, BC: Tatlow House, 1979). ↩︎

- Bluesprint: Black British Columbian Literature and Orature (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp, 2002). ↩︎