I recently worked on a piece where the editor suggested I change my word choice from “praxis” to “practice.” I asked if he thought I was perhaps misusing it in some way that I wasn’t aware of, but he never responded. At that point, my thinking was stalled at Marx’s 11th theses on Feuerbach: “Philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.” To formulate praxis as plainly as possible, stripped of citation, and against delighting in its complexity, I consider it as theory and practice that works towards social consequence, the intersection of thinking about, or at once with, the before, during, and after of an action or series of actions meant to shift the conditions of our political situation. Claiming praxis also indicates the possibility of lacking resolve if we become satisfied by the immediate outcomes of a singular action alone.

When I say intersection let’s just avoid lofty interdisciplinarity, or the gentle brushing up against or casual bumping into of thinking and doing. Praxis is heavy in meaning and resonates like a pronouncement. As a word that invokes intention and consequence, it also echoes a space evacuated of promises we’ve seen made and unmade by movements and broken experiments. We could swim in histories of thought or action, but in histories of praxis we non-canonically splish splash. My thought here is that while theory without practice is the practice of breaking promises, practice without theory strikes me as a kind of routine stroll, unwearied by, or expectant of, the equal parts violence and poetry repeated in the scenery.

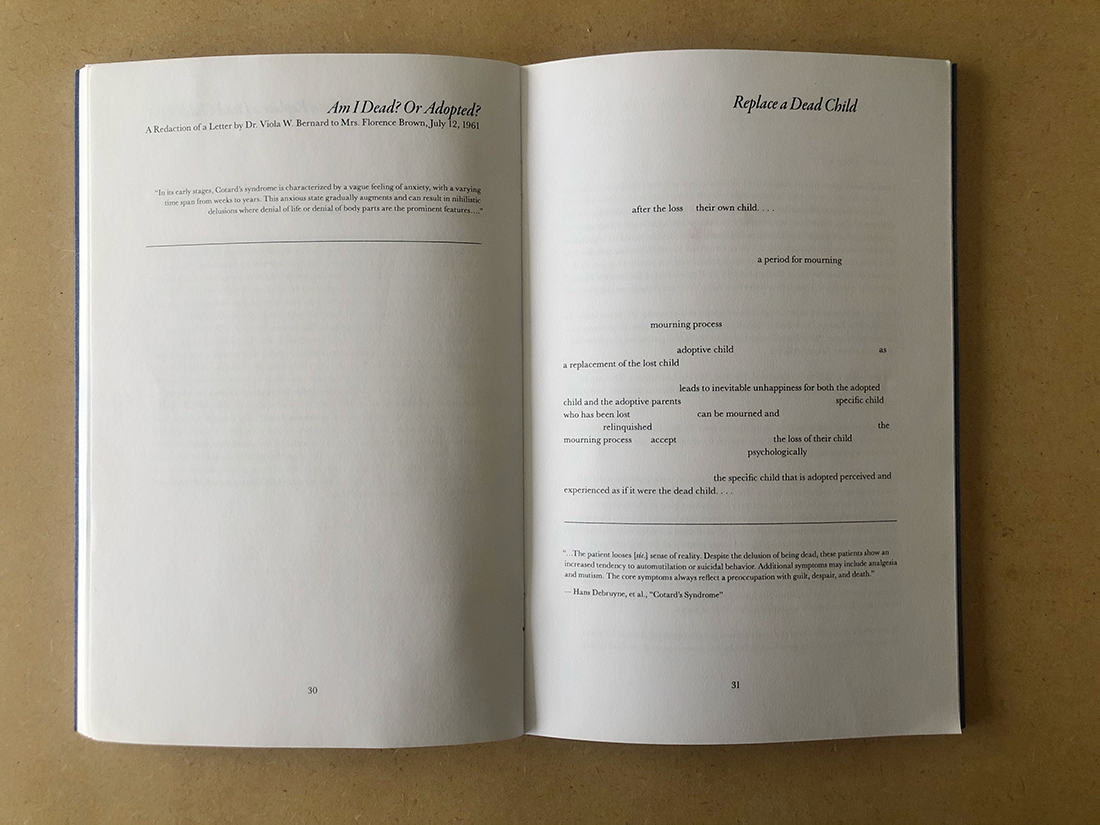

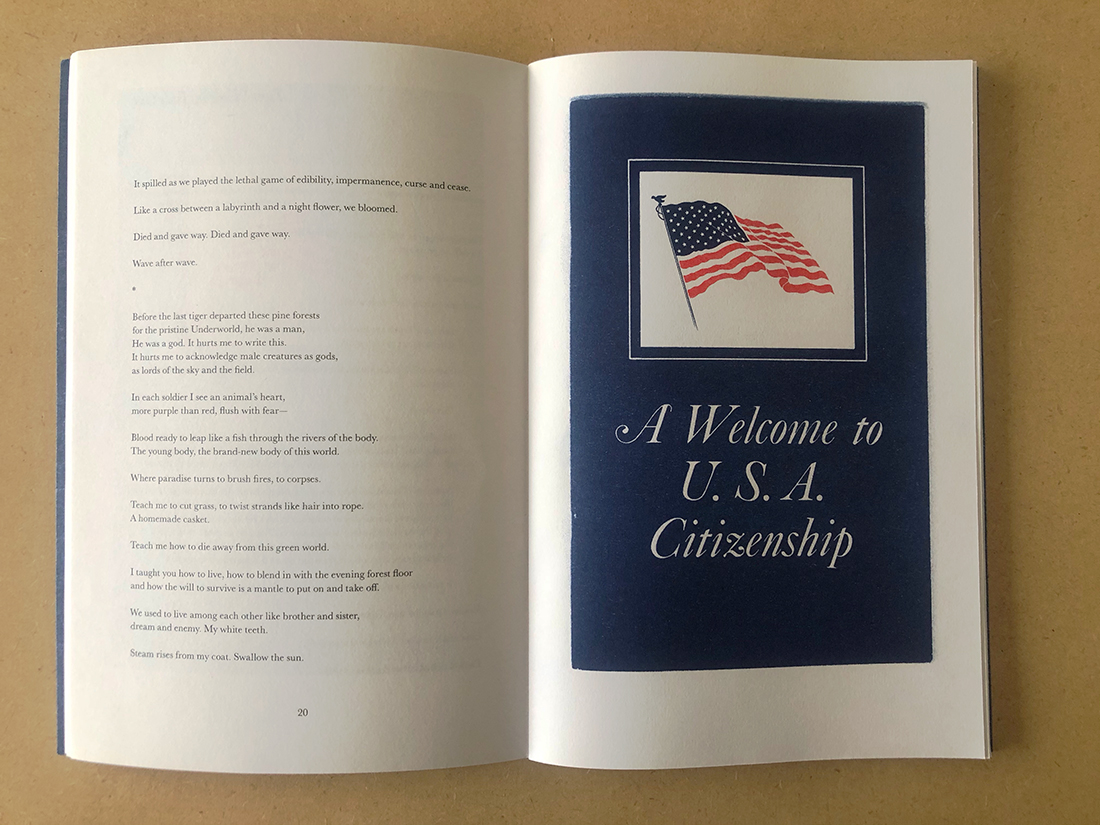

In Sun Yung Shin’s granted to a foreign citizen, we read her poems between—or as an addendum to—archival and government materials pertaining to bureaucratic mechanisms of US Immigration and transracial adoption following the Korean War. The publication includes scans from a booklet Sun Yung received at her own naturalization ceremony in 1979 and a letter to “friends” from Harry Holt—one half of an evangelical Oregonian couple who arranged hundreds of international adoptions for American couples through proxy adoption.

Through the collaging of poetry, personal, institutional, and historical matter, Sun Yung’s compilation contours the bureaucratic and conspiratorial shapes that process this manufactured loss. This drawing can be traced through American imperialism, the exploitation of weak policies, and the assertion of nation as nature, and therefore nurture. The adoption history Sun Yung presents illustrates a nation state’s failure to protect those that are introduced into its border family. Instead, it launders foreign identity, language, and security into the moral currency of white American families who love God and saving all his children. In her poems, the lack of agency that transracial adoptees, or children in general, have in their own material rescue from contexts created by parental loss, national conflict, and social abandonment is disorienting. My disorientation is not a result of reading Sun Yung’s poems, which parse alienation from language and identity, but is provoked by the selected documents that frame the poems and present the end of autonomy as a gift, or a rescue.

The subject of philanthropy recently came up in my study group. We were discussing whether the role of the middle class was merely to widen purses, or whether the purse by nature excludes this class from revolutionary processes. Since that discussion, my instinct has been that there’s no praxis in philanthropy, which is critical of philanthropy as an action without thought, inverting Marx’s critique of Feurbach’s theory that proceeds without action, an impractical force, unchanging the world. Contrary to what philanthropy implies, the social consequences of charity are trapped in a transaction between the philanthropist and the rescued—in this case, the adopter and the adoptee—one that affirms that the philanthropist is good, and the rescue is received in gratitude, or furthermore in servitude. In its assumed fidelity as a transaction, philanthropy hastens to conclude social conformity between two uninvolved yet guilty parties, without parsing the crime.

To think of philanthropy without meditating on the fruition of the crime reminds me of this remark by Harsha Walia, and summons repressed recollections I have of people answering the call for redistributive justice with the resolve, “I just want to give people money.” After reading Sun Yung’s work, the shapes of such sentiments as “I just want to give people money” begin to share a similar contour to “I just want to save the children.” Sun Yung’s poetry offers the shape of a manufactured loss (is a loss) as the negative to a manufactured rescue (can be a rescue) that lingers on the pages of granted to a foreign citizen. When we process the fragments that reproduce loss and rescue, the mechanisms, policies, and self-motivated pieces of that which the nation state can claim as its philanthropic praxis come fuller into focus. In maintaining the orthodoxy of family mirrored in the nation—offering opportunity for the citizen to be an ethical participant who decries this humanitarian issue, but not that one—such orthodoxy compels the complex movements (of populations, of politics) and the individuals within those movements to become subject to grotesque tests and odds. [1]

In the publication’s Appendix, editor Godfre Leung describes the development of the US Korean adoption industry (in collusion with the Korean state) in tandem with the policies that facilitated the Sixties Scoop in Canada. Furthermore, he outlines the metrics that determine the value of certain populations over others, citing “the symbolic value of the rescued Korean war waif” as outweighing the utility of xenophobic immigration policies. Accordingly, a humanitarian America is functionally more American than American America.

[1] Anne Boyer and Sophie Lewis, Staying with the Violence: Womb Work and Family Abolition, presented at the ICA London, May 21, 2019. During the Q&A period, Lewis was questioned about how immigration and refugees factor into family abolition and the border, to which she responded, “The institution of the family as the mechanism, amongst other things, [is what] you have to conform to, or ape, to mold yourself into to cross the border and “naturalize” as we call it. This is why the border regime is effective to tear children, their caregivers, their comrades apart.”

granted to a foreign citizen by Sun Yung Shin was published by Artspeak in 2020.