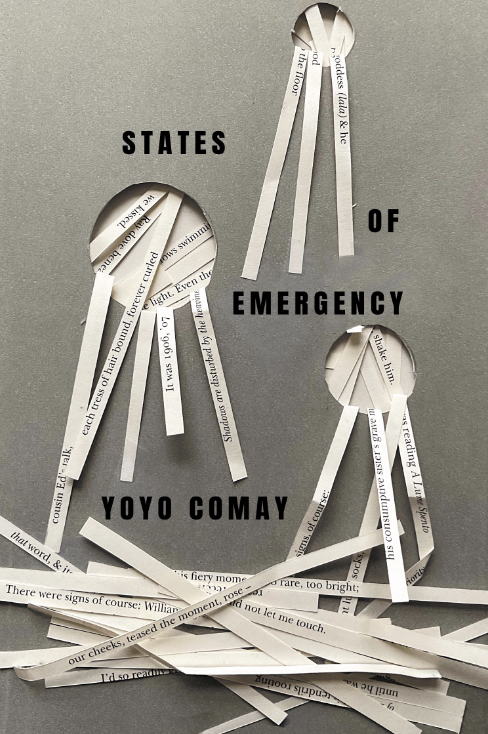

States of Emergency by Yoyo Comay was published by Véhicule Press in 2023

There is a crepuscular quality to Yoyo Comay’s wildly gut-wrenching debut collection States of Emergency, as though the words that form the tendentious poems assembled in it — “I anaesthetize myself from pain / until pain becomes anaesthetic / narcotic, carnal”1 — were borne out of, literally emerging from, as it were, the hour of twilight itself. After all, can’t we trace the “emergency” in the title to the Latin emergere, meaning to “bring forth” or to “bring to light”?

When Comay writes, “I am catapulted into where I am / and the air concusses around me / . . . / as soon as we are conscious we become parody,”2 we see the potential of poetry, here, to emerge as philosophy in a Hegelian sort of way. Was it not Hegel, in Philosophy of Right, that suggested “[philosophy], as the thought of the world, does not appear until reality has completed its formative process . . . the owl of Minerva takes its flight only when the shades of night are gathering”?3 In Hegel, this owl is the enigmatic signifier par excellence of thought and thinking whose flight appears as a rational choice. Whereas here the poet is catapulted, perhaps against his will, to make of philosophy, of knowing itself, a parody about reality in the form of poetry. As Comay movingly shows, poetry is what emerges from the space of the unthought or the unthinkable, those states of emergency that push up against the very borderlands of what can be counted as traumatically real and therefore, in a way, unrepresentable or impossible to conceive of.

Once upon a time “Auschwitz” was one such name for this — the unthinkable, the unrepresentable, the impossible to conceive of. Today, it might be known by another name, “Palestine.” For Adorno, Auschwitz represented the very limits of poetry itself, the limit of its very possibility — “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric,”4 he bemoaned. While States of Emergency may not be about Palestine, having been published only an all-too-brief time after Israel’s recent attacks on Gaza, the collection feels tragically serendipitous. One can’t read Comay’s work — or any work of poetry after this latest assault — without Palestine on the mind. Comay seems to be asking his readers, inadvertently might I add, what it might mean for us to read (or write) poetry in the face of catastrophic temporality and ruinous historicity. In writing this collection, he appears to be responding to the varied emergencies that threaten to drown us (out) in this current historical moment — the global rise of fascism, the turbulence of financial crises one after the other, the ecological and climate catastrophes suffocating the earth and all that exists on it, the increasingly militarized and surveillance-drenched existence we are expected to painstakingly eke out day in and day out. All of this feels banal, even mundane, in a way, in these heady yet highly mediated times. For Comay, “the mundane is not sweet, it is heartbreaking / the word heartbreaking is heartbreakingly mundane.”5

And so, what we see here, as exercised by the poet, is an act of refusal, a direct refusal of the Adornian injunction against poetry. Comay is very much like his contemporary Anne Boyer in this regard, the erstwhile poetry editor for The New York Times Magazine. In November 2023, Boyer resigned from her post in a show of solidarity with the people of Palestine. She concluded her now-famously arresting letter of resignation by suggesting “[if] this resignation leaves a hole in the news the size of poetry, then that is the true shape of the present.”6 Both these poets, Comay and Boyer, are acutely aware of the power of poetry in the apocalyptic here and now. There can be no easy reading of poetry after Palestine and yet neither can poetry be censured, refused, nor can it simply cease to exist — it must serve as an anxious eye on the world, a necessary witness in frightening times. Comay asks, “[does] the world scream at the eye / or does the eye scream the world at us?”7 His poems are a scream, not so much into a void. Rather, they are a scream remade into the shape of the present, this shape being a hole, an open wound.

Who knew better about open wounds than Freud, the father of psychoanalysis? Still further, was it not Freud who suggested that poets would make the best psychoanalysts? Comay follows this meditative tradition of associative exploration in his closing litany:

this is the end

of the world. no, this

is the end of

the world. no, this is

the end of the

world. no, this is the

end of the world. no, 8

The collection ends with a comma, leaving the book itself like an open wound, a hole as it were. Perhaps the task of poetry is not about filling in the hole. Wounds never truly disappear, do they? Dehiscence is always on the precipice of taking place, scars almost interminably remain. Comay knows this to be the devastating truth about what it means to write in the present, or rather, to write the present as that which emerges from the wound. He refuses to end the book, and the world with it. Perhaps the task of poetry is to write the wound into appearance and to refuse to end the world even as we bear witness to it ending around us.

- Comay, 23. ↩︎

- Comay, 22. ↩︎

- Hegel, Philosophy of Right, (Kitchener: Batoche Books, 2001), 20. ↩︎

- Theodor Adorno, Prisms, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1983), 34. ↩︎

- Comay, 25. ↩︎

- Anne Boyer, “my resignation,” Mirabilary. Substack, November 16, 2023, https://anneboyer.substack.com/p/my-resignation. ↩︎

- Comay, 74. ↩︎

- Comay, 78. ↩︎