It took only a handful of years for Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response, better known by its acronym ASMR, to gain a reputation beyond that of a difficult to describe physiological quirk. It took even fewer years for a YouTube-based cottage industry to spring up around it, with thousands of “ASMR-tists” uploading millions of videos in which they whisper, crackle plastic, and gently perform skits in hushed settings like spas or doctors’ offices—the better to simulate the soothing sounds and individualized care that create the small, skin-tingling moments of euphoria sought after by so many.

There’s something vaguely eerie about the way ASMR lays bare how little we are in command of our emotional reactions, and how easy it is for a stranger, separated by a screen, to elicit something primal and uncontrolled in the body—to create a feeling of closeness where there is none. ASMR videos might be poor imitations of intimacy—the whisper in the ear, the feathery touch—but it’s enough for Justine, the narrator of the story “Personal Attention Roleplay,” to find solace in.

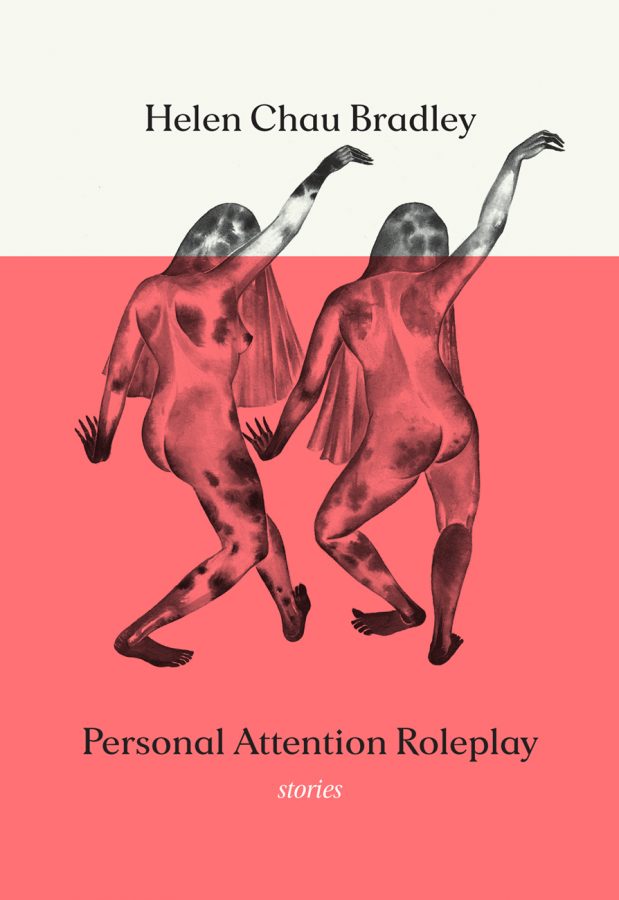

The titular short story in Helen Chau Bradley’s debut collection, Personal Attention Roleplay (Metonymy Press, 2021) begins as a codependent friendship ends. Losing herself in the consolatory “crawling yet pleasing sensation” of ASMR videos, Justine turns inward, toward the abundance of YouTubers roleplaying aestheticians, reiki healers, and makeup artists. These women, faces glowing out of the blue-light of the screen, massage and primp and pluck their way through moments of ersatz connection, in a parasocial entanglement that is, for Justine in her moment of heartache, replacement enough.

Justine’s story ends as it must, in a surreal, inexorable dissolution, the character unable to maintain any real attachment to the outside world, resulting in losing her friends, her job, and her sense of self. Each story in the collection speaks of desire and the bone-deep human yearning for closeness that follows, even if that closeness remains out of reach. Similarly, “Sheila” tells the story of a young mother attempting to cajole her old piano teacher into giving her daughter lessons, haunted all the while by a former musical rival, a spectre of what could have been; and in the opening story, “Maverick,” the despair of unrequited love for a girl with perfect back handsprings and even better bangs, plays out during the ’96 Summer Olympics.

The specificity with which Chau Bradley imagines these characters and their lives highlights how unmoored and solitary living can be. Whether frozen in the shame of childhood betrayal, or experiencing aching, recalcitrant personal transformation on a pilgrimage in Spain, the characters within Personal Attention Roleplay know that the gulfs separating people can be vast, and the bridges between them are difficult to build. And yet, in seeing the stories come together as a collection after years of being published and performed on their own, there is the sense that the intimacy so often missing is achievable through the simple act of assembly.

One of Chau Bradley’s recent readings is outdoors, the sun dappling the grass in Montréal’s Champ des possibles, the late September chill just arriving. The event is a small patchwork of picnic blankets clustered around a low wooden stage, quiet laughter ripples through the event’s attendees, many of whom are friends and peers. There is an understated resonance in Chau Bradley’s mellow voice that stimulates an undeniable thrill in the ears of their listeners, comparable, perhaps, to the gentle crinkling of plastic right next to a microphone. The adolescent Hannah of “Maverick” arguably says it best: “I have no idea how to do an illusion.” But she shouldn’t have to since what we crave is the real thing. As the stories in Personal Attention Roleplay unfurl, and the park reading attendees experience them together, the rareness of such closeness becomes all the more palpable.

Personal Attention Roleplay was published by Metonymy Press in 2021.

Alyssa Favreau is the author of two books: Janelle Monáe’s The ArchAndroid for the 33 1/3 series (Bloomsbury, 2021) and the New York Times best-selling Stuff Every Graduate Should Know (2016). Her work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Hazlitt, Autostraddle, and Popular Science, among others. She lives in Tiohtià:ke/Montreal.