“The house still there online the street, / the broken fence / the dining room window,” writes Erín Moure in her chapbook Retooling for a Figurative Life (Vallum, 2022). Like the speaker, I have found myself reaching for Google Maps street view on my phone to reaffirm the permanence of a lost place from my childhood—in my case, an old ladybug sandbox, a painted purple door. The image that appears on the final page of Moure’s chapbook maps out a similar kind of place—a black and white photo of a backyard in Calgary, Alberta—ensuring its permanence from the fuzzy loss of memory and inevitable changes to the physical space. Much like these digital images that have the ability to preserve forgotten places, language serves as an attempt to remember. However, as we learn throughout the chapbook, language is not only capable of preserving its subject in print, but also, recreating forgotten histories and counteracting forms of erasure.

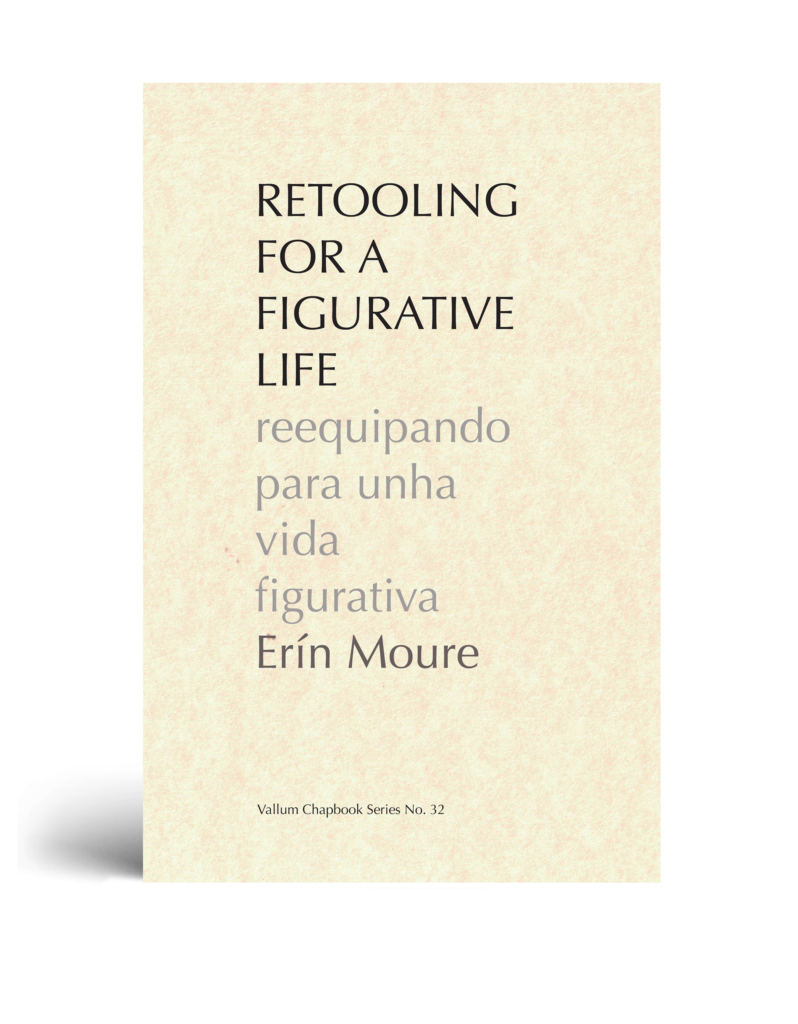

The chapbook is a slim twenty-eight page collection of short poems published as part of a twenty-five part series from Vallum, a Montréal-based literary magazine and press. Moure is an established and prolific writer, having published many full-length collections of poetry, and there is something intimate about reading this shorter project, like a small, hidden artefact of the literary world.

All of the poems in this collection centre on language and its connection to objects and images. In “Fill,” for instance, Moure presents the snow as engaging in a form of literary expression by explaining how the snow crystals create marks on the speaker’s boot “just like writing.” More than a mundane meteorological occurrence, the snow becomes rife with linguistic metaphor while also playing on the paradox of language: on the one hand, words can capture a moment perfectly, but on the other, they can freeze and immobilize their subject. Similarly, Moure knows how to freeze a moment in time, and lines become almost-epiphanies in this chapbook: “For a moment, life’s “if ” triumphs. / No matter how small.” The staticity of the image is clear in the vignettes presented, but then we remember that these are only memories preserved in the artifice of language. “[A] girl walking across the lawn in 1969 is not there,” she writes, just as the speaker makes clear in “Beside” that “[a]rtifice won’t do.” Indeed, while it is capable of preserving a particular moment, Google Maps only captures the surface of the world and its streets.

A similar questioning of artifice occurs in the poem “Sikanni,” in which we wonder about the photo of the bridge and the trees, and the speaker’s choice to “mention the name of a river named for the People on the Rocks.” “Go ‘google’ it,” we are told as an answer. But much as Google maps cannot adequately capture all that constitutes a place, neither can a quick Google search encapsulate an erased history. Below the image, the caption also registers how the history of Black soldiers was erased from literature,¹ and just like that part of the story is blotted out, so is the word on the side of the page, instead appearing in grey text: permafrost. The girls in “Detour” are crossed out too.

This visual effect on the page is one of the many kinds of experimentation that the form of the chapbook encourages. If retooling is the goal, then this more experimental format seems the perfect place in which to do so. Although many visual forms of experimentation occur in the Vallum collection, there is a kind of linguistic experimentation through the many word games Moure plays. Consider, for instance, the seventeen instances of the word “ground” that can be found throughout the collection: out of the ground out of the ground out of the ground out of the ground out of the ground from the ground out of the ground out of the ground in ground on the ground ground out of the ground ground’s glacial here on the ground off the ground from the ground up ground up.

Moure’s use of the word “ground” in these different, though often closely related contexts—as the words “from the ground up” and “ground up” illustrate—is characteristic of the way she uses language to explore the similarities and differences between words as well as their etymological roots. But these are more than just games that leave the reader unsure what to expect next; through the many ways the word “ground” can be transformed, language itself is retooled.

The title of the chapbook reveals this aim. To “retool” is “to organize something in a new or different way in order to improve it.” ² I wonder: if to retool is to adapt, to alter, to make more useful, then what is the figurative life we are retooling for?

- In Moure’s words, “The Long Trail: 341st Engineers on the Alaska Military Highway 1942-1943 (Charlotte, NC: Herald Press, 1944) makes no mention that Black soldiers had any role in spanning the fierce and fast Sikanni Chief River.”

- As the Cambridge English Dictionary notes, the word “retool” is often used in the context of factory work and management. Moure, however, employs the term in a different way that subverts these industrial and corporate connotations.