Rehab Nazzal’s Driving In Palestine, presented by Vines Art Society and SAW in conjunction with the 11th Annual Vines Art Festival, was on view at Vines Den from August 9 to August 30, 2025 in Vancouver, BC.

Watch tower, barricade, checkpoint, gunpoint, surveillance camera on camera, officer, wall, wall, wall, wall. The sound of a drone in the gallery instructs me on how the body constricts under hostile eyes.

Through the documentation of immobility in the West Bank, Palestinian-Canadian artist Rehab Nazzal’s Driving in Palestine creates an opening into life under occupation. Curated by Stefan St-Laurent, Nazzal’s spare greyscale photographs publicize the infrastructure of Israeli apartheid and its imprisoning impact on Palestinians. Framed photographs of watchtowers fill gallery walls floor to ceiling in one room, while larger photographs, maps, videos, and appropriated signage describe the oppressive control of segregated Palestinian roads in the next.

I am simultaneously inspired and embittered by the freefall of other industries’ failures that become the work of artists: Nazzal’s oeuvre captures the reality of zionist occupation grossly omitted from Canadian media. She does so not through the conventional channels of journalism, but through contemporary art. Soured after over two years of having Palestine on the lips of everyone against genocide, I imagine how this collection of images taken from West Bank roads might be distinctly quotidian to the average West Banker, in contrast to the surprise of those of us whose countries fund the zionist occupation. Throughout the exhibition, underlying tensions vibrate with intensity.

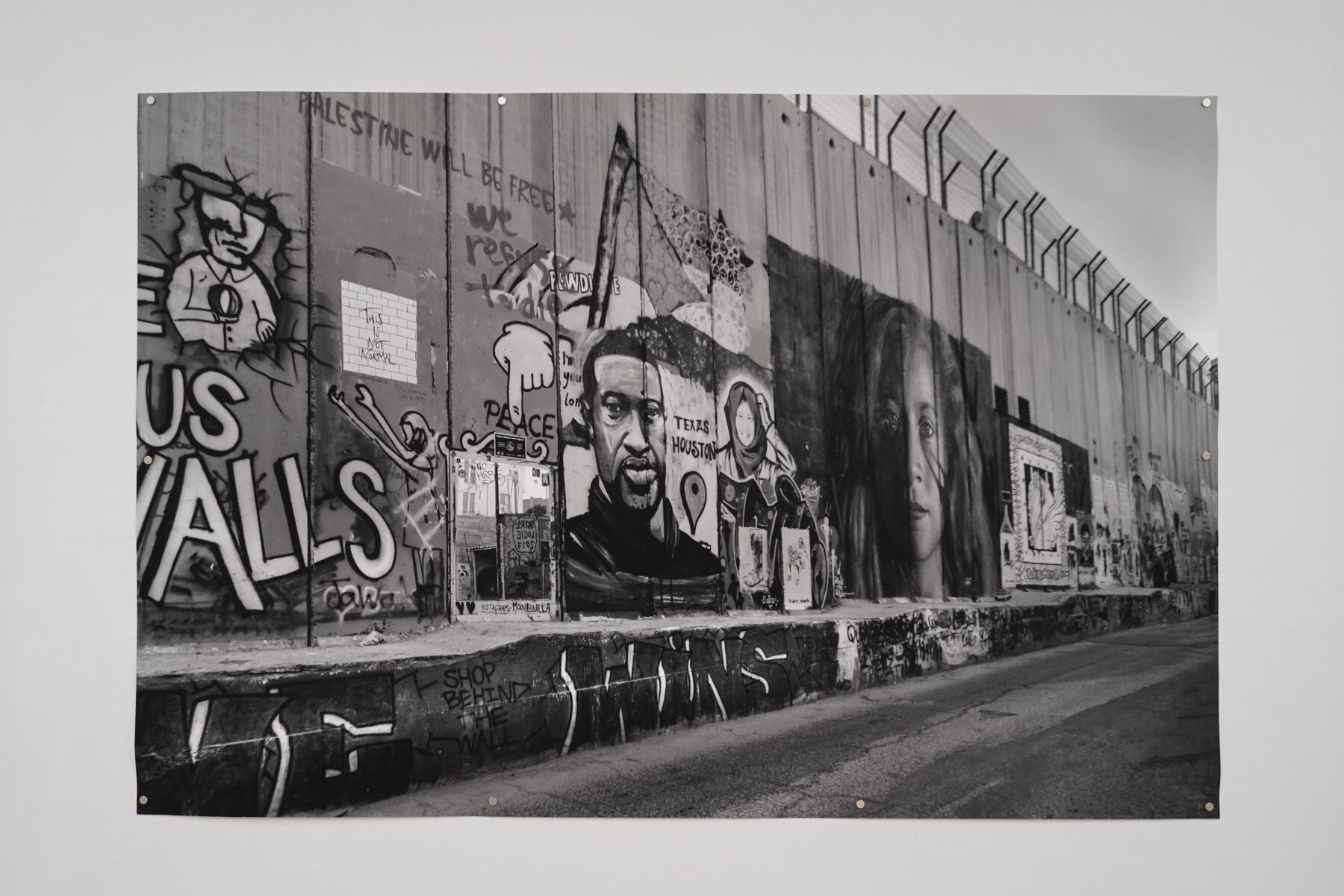

The architectures of apartheid are brutal. At the same time, when contained in a picture on a gallery wall, the apartheid wall appears brutally simple. In this way it confuses me. In one photograph, the apartheid wall surrounding Jerusalem seems to end in the midst of a road. It stands on the edge of space to mark where Palestinians can attempt to traverse their own country, at their own risk, and where illegal settler occupations begin. In a reproduction of a hand-drawn map, Nazzal traces the route she has driven through the West Bank. Driving, she reminds us in an artist talk, because the IDF are liable to shoot a Palestinian openly documenting Israeli apartheid.1 Nazzal traces the geography of the land along the shape of apartheid walls, blockages, and roads that end and slink to stretch a thirty minute drive into one of unpredictable hours. Like oil or minerals, geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore writes that time itself is the resource that is extracted by carceral systems.2 I imagine the blood that pumps through Palestinians’ veins being sieved, collected, and dumped at temporal intervals, denied that which makes a life lived. By Gilmore’s logic, Nazzal is documenting extraction: the extraction of time itself, and life itself, through policing and imprisonment. One photograph is centred in a room: an imposing concrete divider covered in paintings, words, and drawings. At the wall’s highest point, the words Palestine will be free, we refuse to die. I’m reluctant to imagine that graffiti on the apartheid wall is where time steals itself back into life through art. At the same time, I can’t help but feel a heartbeat in this image.

The constriction of the exhibition’s contents contrasts with the warmth of Vines Den. The table where one might typically find exhibition ephemera upon entering is expanded to include posters, leaflets, fundraiser sales, donation QR codes, harm reduction supplies, and a calendar of twenty programmed events under the banner of Driving in Palestine Freedom School. Fold out chairs and tables stowed away, plates and napkins out and ready for a shared meal – the evidence of activity throughout the space reflect the ways that Driving In Palestine resists passive consumption, and invites cultural, intellectual, and political activation. While Vines, SAW, and grassroots organizers work to bring Driving In Palestine to the public, the absence of familiar private funders and well-resourced institutions in contemporary art are palpable in the exhibition of this internationally significant work.

Just as drones bore down on me upon entering the gallery space, soft chirping reaches out at the end of the last room. Hidden, a couch rests facing a wide projection that fills my view. I remember the poem by Marwan Makhoul:

In order for me to write poetry that isn't political,

I must listen to the birds

and in order to hear the birds

the warplanes must be silent

The eye of Nazzal’s camera politicizes even the birds, as only a Palestinian who dares to love their country can. This is Healing Moments – a video that catches us softly at the end of the road. From the window of a car, Palestinian grass trembles quick in the breath of the Arab sky, and knows nothing of waiting for officers. Time expands in the sway of Palestinian flowers while moments become sensations that exceed the duration of a checkpoint line, an apartheid wall, an eye meeting the end of a gun. At this moment the trees appear to know, as any Palestinian who dares to love their country does, that a long, unfurling Palestine is coming.

- “Artist Rehab Nazzal Shot in West Bank,” Canadian Art, 2015, https://canadianart.ca/news/rehab-nazzal-shot-in-west-bank/. ↩︎

- Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Abolition Geography: Essays towards Liberation (London: Verso, 2022), 474. ↩︎