Anna Moschovakis’s Participation was published by Book*hug in 2022

Participation is a story about two reading groups, Love and Anti-Love, the former based in a city and the latter in a village some 150 miles away. Love’s members once met in person but now communicate over email, perpetually adding to their syllabus of poets, philosophers, and theorists—Bersani and Barthes, Ovid and Aristotle, hooks and Sedgwick.

Anti-Love’s members gather after hours at a café-bar, discussing texts that speak to their righteous anger and desire for revolution. And who wouldn’t be angry? The news, blaring from TV screens and popping up on phones, is dire as usual: white supremacists march in the streets and environmental disasters loom.

E, who starts off as our narrator, belongs to both groups. She spends most of her time in the village, living in a trailer that’s been converted, collage-like, into a house. She works at the café-bar where Anti-Love meets and in an information sector job where she’s met someone she refers to as “the capitalist.” She also frequently commutes into the city, where she rents a room in a shared apartment and pursues training as a mediator. When Participation begins, E’s mediation mentor has mysteriously disappeared, leaving her in an unsettled, in-between state that also gives her more time to catch up on Love’s syllabus. As she thinks about eros, agape, and philia, she starts exchanging emails with S, a fellow member of Love. Gradually, E and S are brought together as are the two reading groups—a kind of merger.

E might take issue with my synopsis. It’s a little too tidy, too linear. From the beginning, E questions storytelling’s relationship to reality. In ordering events, privileging certain perspectives, and drawing a frame around its subject matter, a story can achieve coherence. But this, E knows, is often false or misleading. In fact, halfway through the novel, E stops narrating altogether. “I’ll leave you here, hand myself over,” she tells us, and from this point on, another, unnamed narrator takes over. “I know it’s sudden,” E explains, “but there are parts of this story that can’t be told from the inside. I don’t trust myself. (Why should you?)”1 Still, as she knows, stories have their uses. They’re what the narrator calls “a safe emergency,” a means to freely explore fraught material without getting hurt.

Participation revolves around a series of questions. How can our subjective experience of reality be shared with others? How can we love those who are different from us, marked by different joys and wounds? The syllabi of Love and Anti-Love may provide a formal means of weighing these questions, but they ultimately encourage reflection of a broader kind. What syllabus do we follow as a society? What have we learned to desire, to fear, to accept?

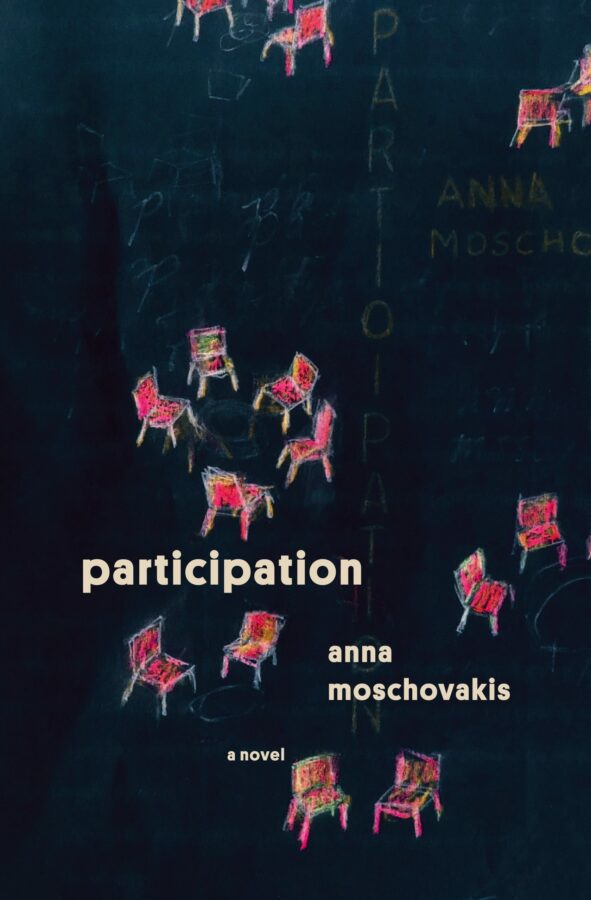

These questions aren’t purely theoretical. For one thing, the tropical storms forecasted by the news finally arrive, followed by earthquakes, battering parts of the countryside and rocking the city. Messages from a liveblog interrupt the narrative, relaying information and directing help to where it’s needed, a reminder of the necessity of mutual aid and care. Moreover, Participation’s characters, like its readers, live under capitalism, a system the second narrator likens to a game of musical chairs: according to its logic, there simply aren’t enough chairs for everyone. But, the novel insists, we might be enjoying a very different world had this missing chair not simply been presented as a game in our childhoods but “as a fact that could provoke instinctual dissent.”2

Lest this account give you the impression Participation is didactic or dull, consider that these critiques of the status quo are preceded by E’s extended fantasy “about the extraction of pleasure from a capitalist,”3 who, lying prone in a playground sandbox, is tasked with explaining the peak-end rule (a cognitive bias that influences people’s memories) while E insistently pulls on his nipple rings. “What if the desire to be challenged could be taught, could be learned?” our second narrator later asks. “A top who knows how much pain to dole out per thrill, how much thrill per unit of pain?”4

Like its characters, self-styled students of the syllabi of Love, Anti-Love, and life, Participation is exploratory, open-hearted, and playful. As a story, it’s a bit of a tease, doling out information bit by bit, deferring closure, jumping around in time, and making use of diagrams and lists—but this is fitting for a novel about desire, narrative and otherwise. Ultimately, Participation is a compelling, charming, and surprisingly sexy exploration of vital questions of selfhood and community.

- Moschovakis, 104.

- 188.

- 61.

- 186.