I am met with a hue that sits between purple and pink. I ultimately decide that this colour that greets me upon entry to Aisha Sasha John’s DIANA ROSS DREAM is purple and not pink — even if the colour is really more a distinct tincture of pink than a purple, and the colour purple does not fully appear until about the 15th or 30th minute of the performance — as I have always believed, despite myself, that the colour purple is the colour of the Black feminine in the same way that light blue is the hue of the Black masculine.1 I wonder what colour represents the Black bodies that choose to inhabit in-betweenness — those who resist interpretation via gendered categorization, thereby foregoing the implications that these limited categories have on our social conditions and perception.

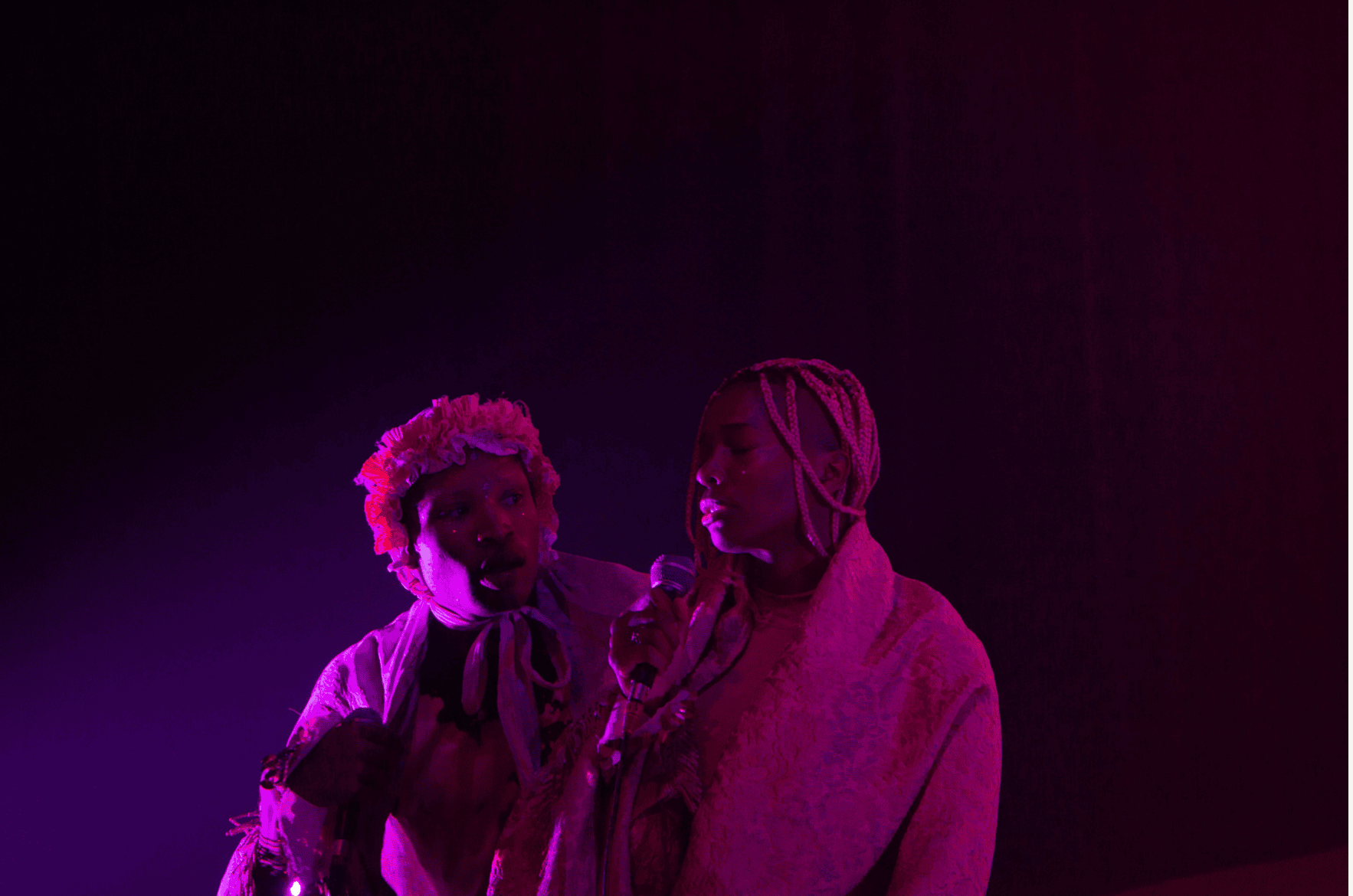

Martine Syms, in conversation with Laura Marks in 2016, stated that the colour purple represents a moment when the spiritual is present in the secular.2 The colour purple then becomes the colour of Black femmehood despite the other — the colour of God. The spiritual that infiltrates the secular is of great importance to me as I think back on Aisha Sasha John’s performance. Once the space became marked by John and her collaborator Devon Snell, it was no longer located in an inconspicuous performance space between Vancouver’s Chinatown and Strathcona. Instead, the space became the playground of Black deity-like figures inhabiting a dreamscape, who paid no heed to the outsiders observing — the outsiders that expected them to do something, to make sense, to reference some unspeakable Black trauma, to comfort them, to show off their bodies, to do all of the things expected from Black bodies who perform in cities such as this.

In DIANA ROSS DREAM, John attends to the question of Black belonging through an amalgamation of dance, light, sound, and costume that brings forth a version of Blackness that does not answer when you call or make itself discernible. The tribute to Black belonging that John presents in this body of work is instead one grounded in abstraction, illegibility, and an intimate chopping and screwing of reference material to cause even the most well-informed audience member to question if they do, in fact, know where each movement and gesture is originating from.

We witness John and her collaborator channel a range of Black dance movements from across the diaspora and the continent, ranging from jumps and twirls, most likely inspired by Kenyan Massai dancers, to kicks and turns that have become staples in the safe haven that is Black ballroom.

The performance in itself is almost silly, jovial, but at the same time it is also divine and powerful; these contrasting aspects of the performance intertwine and become ever more pronounced, particularly when one considers the stakes and possible danger of a Black body being perceived as silly, jovial, powerful, and divine in public space. The stakes of attempting to belong, the stakes of the perpetual performance of Blackness, the stakes of “being” while Black. I am thinking about Christina Sharpe and her citing of the Black as the site of imminent death.3 Perhaps this performance was not, in fact, set in the distant utopic spiritual plain, but in the afterlife. Does Black belonging only come after death? And are the colours purple, pink, green, and blue so present in this performance present also in the hues of dreams . . . the hues of the Black afterlife?

Is it going to work?

At some point in the performance, John and Snell melodically hum the words. Is it going to work? Is what going to work? Will the utopia of our dreams come to fruition in this lifetime or in the ones that are to come? I return to the stakes — the stakes of a neverending becoming, the possibility of a Black life beyond and after death. Is to be Black in this world a perpetual inhabitation of the in-betweenness of the living and the dead, the human and the subhuman, the purple and the pink, the spiritual and the secular, the valuable and the worthless?

In this work, John proposes a version of a Black past, present, and future that is dissident and implicating, despite its apparent effervescence. This body of work is not evocative of Black joy; it evokes something unfamiliar to some, but not to me. The feeling it evokes will remain unsaid for now. You will become familiar with this feeling in due time.

- I am thinking of the title of Tarell Alvin McCraney’s autobiographical drama In moonlight black boys look blue, which inspired Barry Jenkins’s 2016 film Moonlight. ↩︎

- Martine Syms was in conversation with Laura Marks on October 12, 2016 at the Djavad Mowafaghian World Art Centre as part of Syms’s solo exhibition Borrowed Lady, curated by Amy Kazymerchyk, which was held at the SFU Audain Gallery in Vancouver from October 13–December 10, 2016. Their conversation can be found at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IkQLbRMAFoY&t=1202s. ↩︎

- Christina Sharpe, In The Wake: On Blackness And Being (Duke University Press, 2016). ↩︎